The Hollinwell Incident: What lay behind the Fainting Field?

- Published

Hundreds of children collapsed at the event, with many taken to hospital

In July 1980, hundreds of children began collapsing at an annual show held in a Nottinghamshire mining community. Many were taken to hospital, reporting symptoms of fainting, nausea and dizziness. But to this day, some of the families affected do not accept the findings of an official report that blamed "mass hysteria". BBC Radio Nottingham asked whether there could be another explanation.

On the face of it, the organisers of the 1980 Hollinwell show could not have chosen a more perfect day.

The day of 13 July dawned hot and sunny. The community showground, near Kirkby in Ashfield, where the event was to be held, was a bustling mass of families and stalls selling hotdogs, candyfloss and ice cream.

From early on, coaches started to arrive, packed with excited children, some of them as young as five. They were dressed in elaborate majorette uniforms, some carrying drums.

These children formed the basis of the marching bands who were due to perform at the event.

The world of marching bands was often associated with mining communities and saw groups from across the country travelling to compete at different events.

"It was just a thing in the 80s, getting dressed up and having your sash with all your medals on," recalls Clair Brown, who was eight years old at the time.

"We did events, we did galas, and sometimes we marched the streets."

People at the scene said it "felt like a panic"

Clair, from Kirkby in Ashfield, was at the event with her grandad Ken Hughes.

She played the tambourine in a band and remembers being "really excited" as the event got under way.

"It was called jazz bands," says Judy Vaughan, who set up the Zingaris band.

"You'd get there in the morning, you'd line up, you'd do a street parade and you were judged for music and marching.

"Then when you got to the field, you went on and did a 15-minute display and you were judged again."

Clair remembers going on to the field and "doing her bit".

"I can remember it all stopping, all of a sudden," she says.

"I think I can remember seeing a couple of children on the floor and panicking. Then I remember going home."

Around the ground, hundreds of children were collapsing.

Clair's grandfather Ken says: "People didn't know what was happening.

"All of a sudden, there were ambulances coming through the gate. It felt like a panic then.

"All we were doing was running about the field looking for our own children.

"As we were running to get to Clair, there were kiddies down, with their parents gathered around them.

"One of the biggest frighteners was that many ambulances. People hadn't seen so many since the Second World War."

As police arrived and began to clear the site, increasingly frantic announcements were made over the public address system.

Organisers initially feared the cause could be food poisoning and people were advised to stop eating the sweets and drinking the water.

Judy Vaughan (centre) had to take children to hospital when they began to feel ill on the drive home

Band leader Judy Vaughan was collecting her charges together to usher them off the site and on to the coaches.

"As we were setting off to come home, one of the girls was crying," she says.

"I went to the back of the bus to see her. Her eyes were red and sore.

"She said 'I don't feel well. I don't feel as though I can sit up straight.'

"We'd got another girl doing exactly the same. We turned the bus around and went straight to Nottingham City Hospital. It was panic stations."

Staff at the hospital bathed the girls' eyes and later discharged them and Judy was able to return the other girls to their families.

"I got the reports the following morning, there were a number of band members who had got home and then gone to Chesterfield Royal," she says. "It was the same thing: runny eyes, feeling sick and wobbly."

Meanwhile, Clair - who had left the event two hours earlier - was playing in the back garden when she started to feel unwell.

"I can remember this white, frothy foam coming out of my mouth," she says.

Clair's mum, Ann says: "She came in and said 'Mummy, I don't feel very well. She was frothing at the mouth.

"Her eyes were running."

The official report concluded the incident was as a result of mass hysteria

Ann rang for an ambulance which took Clair to Chesterfield Hospital. Their local hospital was already full due to other children who had been admitted following the event.

Clair remembers feeling frightened. "I was a little girl, on my own. They wouldn't let my mum stay," she says.

"They kept her there for a couple of days. They never said what caused it so I don't know what the doctors thought," says Ann.

"I got a visit from the council. They asked a few questions, then they went away and I never heard no more."

According to the official report by Ashfield District Council's environmental health department, medical professionals and the police, around 400 people - many of them children - were taken to hospitals following what came to be known as the Hollinwell Incident.

The report, which was compiled in the immediate aftermath of the incident, said: "Most of the children were concentrated in the top corner of the field.

"The children wore tight-fitting uniforms and hats. The children did not all collapse together but for a period between a period of 11.15 - 13:00 BST. They were collapsing five or six at a time.

"Symptoms include sickness, giddiness, pains. Nine people were detained overnight, including two babies a few weeks old."

The report concluded the illness was sparked by mass hysteria - a phenomenon where episodes such as illness or fainting seem to pass between large groups.

However, this left many families feeling dissatisfied, including Ann, Clair's mum.

"My daughter was home two hours before she was took poorly," she says. "So, where's your theory there?"

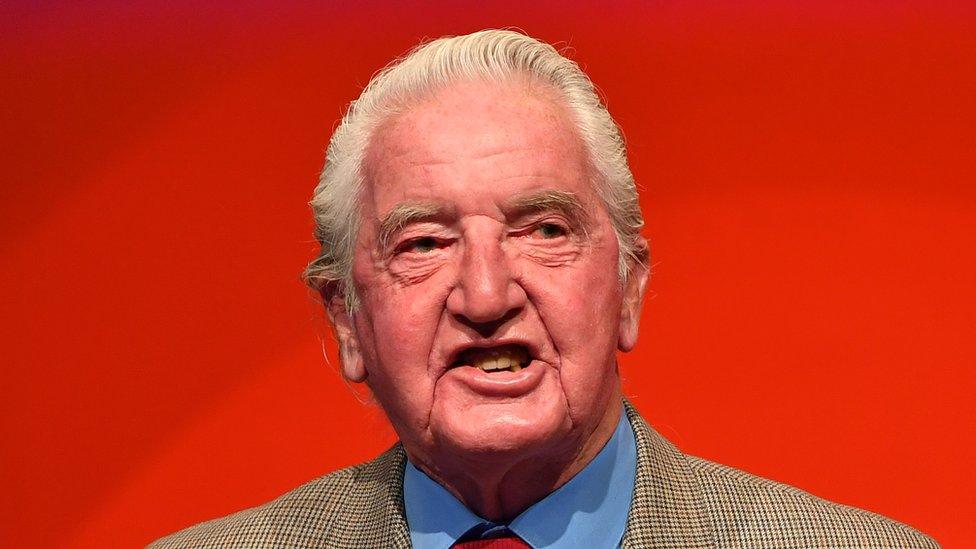

In 2014, former Labour MP for Bolsover, Dennis Skinner, expressed the view that authorities had not taken the inquiry seriously.

"They dismissed this incident as quickly as they could," he says.

"I remain concerned about how it happened and I don't believe it was properly investigated.

"These were working class kids and I don't believe they looked into it as meticulously as they would have done had it been at a royal garden party."

Dennis Skinner felt the incident was not taken seriously by the authorities

Over the years, a number of theories have circulated about the cause, ranging from gas leaking from underground mine shafts to the use of pesticides on nearby fields - and even a paranormal event.

Jon Wright, course leader for forensic science at Nottingham Trent University, was approached by the BBC to look back at the case to see if he could shed any light on the incident, more than four decades after it took place.

"Looking through the report, there are a number of things that are initially blamed," he says.

"Food and water poisoning get discounted. Mass hysteria [is what] it was actually put down to. Also, the cleaning of the toilets."

He says he believes the explanation for the children's illness comes down to "some form of chemistry".

"Looking at it, the reactions to it are reactions to some form of foreign substance," he says.

"The only two substances we have on site are the pesticides and cleaning the toilets.

"The pesticides were apparently sprayed three days earlier so shouldn't have caused any issue.

"The other one was the toilets. The toilets, the report says, were overcleaned."

The report says the toilet block comprised of a portable structure, containing some six chemical closets.

"Over-liberal use had been made of bleaching powder," it says.

"There was a very strong aroma of chlorine and ammonia present in the toilet block which was some 20 yards from where the children had been standing."

'Retching and foaming'

"If you go back to basic chemistry, you don't mix chemicals," Jon says.

"Worst-case scenario, you make things like chlorine gas, which is what they used in World War One.

"Was there a potential for some form of gas drifting across the field? The toilets weren't very far away from these massed bands.

"If the bands were feeling a bit light-headed, getting a whiff of something nasty could have caused them to collapse.

"Chlorine gas also makes you cough and wretch and all these things are accounted for. There is retching, eyes watering, people foaming at the mouth. Did that cause it? It's an open question."

Mr Wright says that while mass hysteria may have played a part in the number of collapses that occurred among the children, "there was probably some form of chemical basis".

"I think it's a combination of factors, very unfortunate," he says.

Since the Hollinwell incident, Clair Brown says she has suffered health problems throughout her adult life.

"I couldn't get pregnant naturally, so I had to have IVF," she says.

"I had to have my left kidney removed and now I have double breast cancer. A friend of mine who was there also had breast cancer. I don't know what anybody else has had further health problems.

"We sit and speak about it and wonder if all of my health problems are connected but you just don't know."

Ashfield District Council's current leader Jason Zadrozny says he no longer stands by the report.

"This was a tragedy and people still talk about it - especially in Kirkby," he says.

"The event was organised by an external group but the event was investigated by Ashfield District Council which was only created six years before.

"We have sympathy with anybody who is still suffering from health implications.

"I can't stand by a report written 42 years ago.

"I have looked into this and it's clear that there are concerns about the accuracy of a report produced decades ago.

"What I can assure residents is that this council takes its health and safety responsibilities extremely seriously.

"Any organisation running an event now has to meet extremely rigorous safety conditions imposed by the council."

To hear more about the Hollinwell Incident, listen to Andy Whittaker's podcast The Fainting Field for BBC Radio Nottingham, available on BBC Sounds.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published22 January 2022