Gough map 'given new life' by researchers

- Published

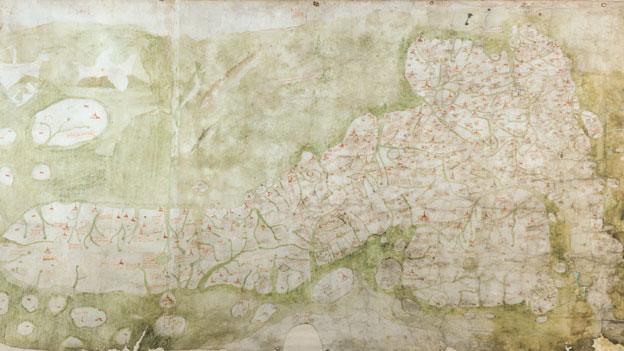

The map depicts Great Britain on its side as it was made before the convention of maps pointing north

The findings of a 15-month project to study the earliest surviving recognisable map, external of Great Britain have been made available on an interactive website.

Nick Millea, map librarian at the University of Oxford's Bodleian Library, explained how a team of investigators discovered the secrets to the Gough map, which he described as "a national treasure."

He added: "It's a very unique piece of cartography and there's nothing else in the world like it - a map of that level of detail from that period of time."

Mr Millea helped form a team of specialists who pinpointed the map's origins to 1375, instead of 1360 as previously thought, drawing on the small differences in English handwriting over the period.

They also confirmed that it was revised in the early 15th Century.

Anglocentric

Furthermore, the use of vowels has given something else away about the Gough map's origin - the map-maker was from the south east of England.

Elizabeth Solopova, a medievalist at the Bodleian Library, said: "The south east is the most accurately portrayed part of England on the map and is represented with the greatest level of detail and precision.

"I also analysed the spelling, fonts and the places of the map. This suggested the same Anglocentric approach and the place names in Scotland aren't necessarily authentic."

Mr Millea, who also wrote The Gough Map: The Earliest Road Map of Great Britain, added: "The difficulty is to read it. It's hard to make out. The handwriting is so strange to a modern eye and a lot of the text has faded over the centuries.

"Spellings weren't conventional - you spelt as you heard. It's long before English was written down in its standard form.

"The use of vowels indicates how the person would have written it down and we know enough about regional accents in the Middle Ages to say there was definitely an indication that this was written by somebody in a certain part of the country."

After joining the project Ms Solopova took two weeks to accustom herself with the map, admitting she found the wealth of information "bewildering and frightening."

"It was very painstaking and hard work. This is definitely the most complex document on which I've ever worked.

"It's not a continuous document so you don't really know where to begin and much of this information is unpredictable."

'Era of change'

Several important clues told the team that the map was revised in the 1400s.

There are signs that the original text was erased and new text written in what Ms Solopova called "an era of important change in English handwriting."

"The handwriting used in the late Middle Ages is known as Anglicana," Ms Solopova explained.

"But this changed and a new script, Secretary, was introduced in the 1380s and 1390s from Italy. It was used by clerks and in the offices of archbishops.

"By the 15th Century it became established as a script for all kinds of texts including books."

Mr Millea said he learnt different lessons from the Gough map.

"I'm not a medievalist. I see a map like the Gough map and think it's a proper map," he said.

"It shows geography and the lie of the land rather than a map showing the world as interpreted for a Christian audience.

"It is the prototype of modern English cartography. It shows real geography as opposed to theology which earlier maps tended to show.

"The additional beauty is you've got at least 600 place names there so it's a wealth of information from the late Middle Ages and it's relatively accurate."

The Gough map was donated to the Bodleian Library in Oxford by Richard Gough in 1809 who is said to have bought it in 1774 for two shillings and six pence.

Drawn on two pieces of sheepskin, the 115 x 56cm (45 x 22 in) artefact depicts Great Britain on its side, before the convention of maps pointing north.

Whilst the map was exhibited for six weeks over May and June it is currently in storage.

"In order to preserve the map for the next 600 years we have to look after it," Mr Millea said.

But the team's findings have been made available on a special website.

"Three different institutions got together to produce this website to bring the Gough map to life and we're thrilled to bits," Mr Millea said.

"It's like that old saying, one map in an essay or report is worth a thousand words."

- Published21 June 2011