Oxford University Museum of Natural History reopens

- Published

A £2m project to fix the leaking roof of a 150-year-old museum has provided the opportunity to painstakingly clean its ageing exhibits.

Specimens at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History were being damaged by rainwater, while others were fading under harsh light.

Conservator Bethany Palumbo said: "We found watermarks on the whales which was crazy. We also had a collection of buckets for emergencies."

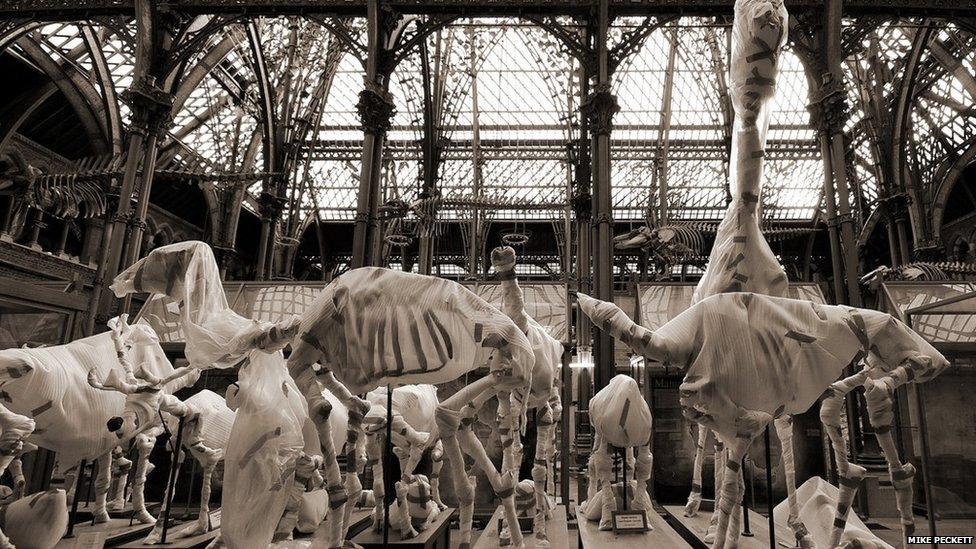

As a result, the museum was closed for 14 months as more than 8,500 Victorian glass tiles were individually removed and resealed.

During this period Miss Palumbo restored the museum's vast collections, with scaffolding set up to carry out conservation work on a variety of specimens, large and small.

She said: "The first time I saw the building I was in awe of how beautiful it was, and then I was shocked at how much light was pouring in on to the collections.

"We've had new lighting installed, which looks incredible, and all the specimens have had a mass clean, including all the big dinosaurs that would be hard to access."

The reopening will see more than 100 century-old specimens given a new lease of life.

Miss Palumbo describes the museum's 4.56m (14ft 11in) long sperm whale jaw as "incredible".

She added: "It's one of the largest ever found on record.

"It's from about 1840 and that was before industrial whaling.

"This was a time when the seas were full of whales and once the whaling started all the bigger ones disappeared and now we just have smaller samples.

"It's absolutely huge and visitors have been touching it over the last 100 years which left a black residue on the surface, which we removed."

A unique specimen due to go on display later in the year is the actual head of a dodo with its skin intact.

"Like many museums we have skeletal samples of the dodo, but we're the only museum in the world that has a skin sample," said Miss Palumbo.

"It is the whole head with the skin attached. It's pretty amazing, there are even a few spindly feathers.

"It's not on display yet - it needs a proper case with proper security and lighting."

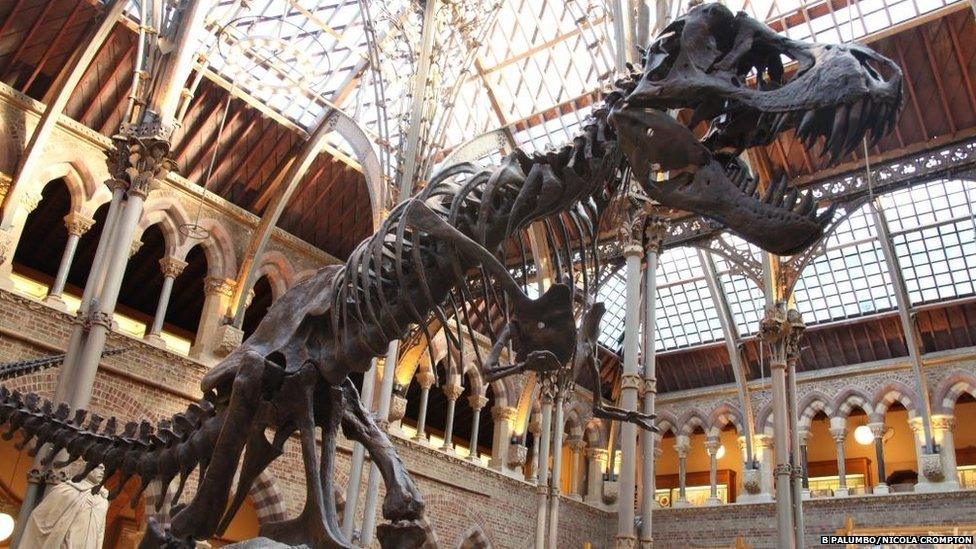

The museum's dinosaur exhibits include "Stan", the Tyrannosaurus rex, and duck-billed dinosaur Edmontosaurus, both cast from skeletons found in modern-day South Dakota.

The Iguanodon plaster cast has been on show for at least 150 years in its original upright pose.

"Nowadays they don't cast them in plaster, they cast them in resin," continued Miss Palumbo.

"It's since been discovered that they walk on all fours. To try and risk changing him now would be dangerous for him as a specimen as he wouldn't survive the transition."

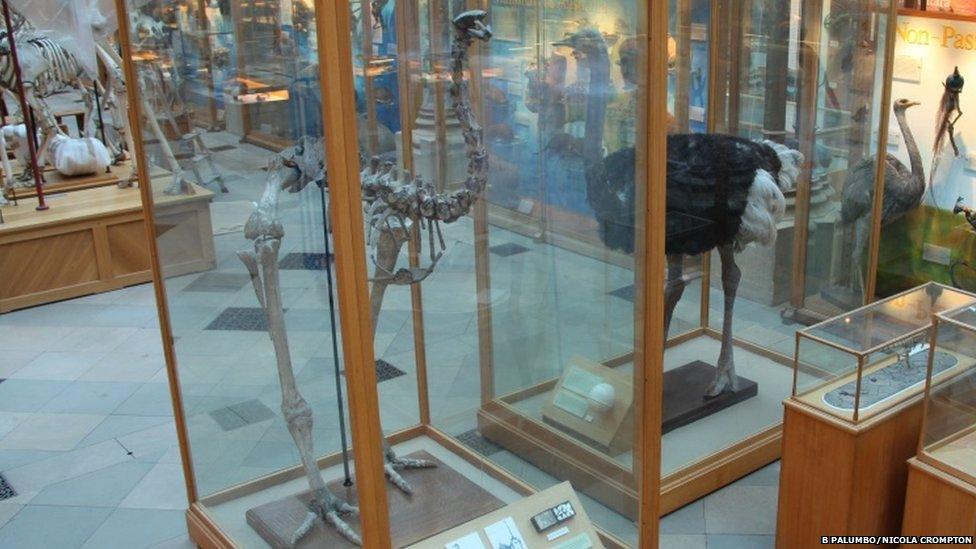

The moa is an extinct flightless bird that gets considerably less attention than the dodo.

The creature died out after the Maori colonised New Zealand in the 13th Century and began to hunt them.

"It's humungous, about 2.5m (8ft 2in) tall, but they've been recorded up to 3m (9ft 10in) tall," explained Miss Palumbo.

"It doesn't get a lot of exposure. It was in a dusty old case in a corner of the museum and when I discovered it I thought it was amazing.

"They were just too huge and were probably tasty.

"The dodo gets all the attention because it's cuter, it's ditzy and slow, and its representation in Alice in Wonderland."

Paul Smith, director of the museum, said: "This has been a long, dark year with the museum closed to visitors.

"It will be very nice to see the doors opened again... and to have the sound of visitors filling the space once more - without them having to move around buckets to collect rainwater."

- Published20 January 2014

- Published1 July 2013

- Published19 April 2013