How the net closed on Oxford's grooming gang

- Published

Nearly a decade after the abuse of vulnerable girls in Oxford began to be addressed, following years of negligence by police and social services, the last of the so-called Operation Bullfinch trials has ended. How did the sex offenders at the centre of the city's depraved underworld finally come to face justice?

Oxford, 2011. For nearly a year detectives have been receiving reports of girls disappearing, some as young as 13, only to return days later, refusing to tell anyone where they had been.

Sometimes they would be bruised, bleeding and half-naked.

For the past few months a Thames Valley Police team has been investigating the cases, but making little headway.

But in the early hours of 14 November, the man leading the small group, Det Insp Simon Morton, made a connection that would spark the biggest criminal investigation in the city's history.

The senior investigating officer said he had just finished debriefing a surveillance team when the "penny dropped".

As he sat in the police briefing room and stared at the names of suspects written on a whiteboard, Mr Morton suddenly realised he wasn't looking merely at a set of sexual predators, but a highly organised crime group.

"I started scribbling like mad," he said. "In honesty, I was annoyed I hadn't seen it before - it was so bloody obvious."

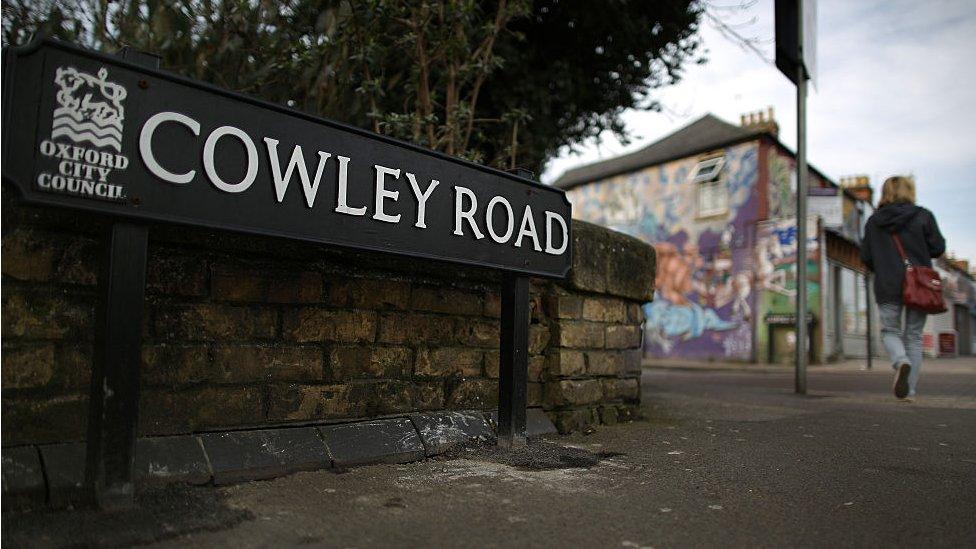

Many of the girls were targeted by gang members on Oxford's Cowley Road

From that moment, detectives and social workers began to identify a web of offenders and expose a criminal enterprise that involved the grooming, trafficking and rape of vulnerable girls.

The affluent university city was soon to learn of the world of sadistic sex abuse that had been flourishing in its eastern suburbs.

Over the past decade and through six trials, 18 victims have recounted their experiences, leading to the convictions of 21 men for offences spanning the late 1990s to the late 2000s.

Over seven years, dozens of jurors have heard how girls were "sucked into the vortex" of the gang.

For legal reasons, the links between the trials could not be reported until the recent conclusion of the final court case.

The men, mostly British citizens of Pakistani origin, operated in the Cowley Road area, where student digs sit alongside family homes, and ethnic food shops and pawnbrokers neighbour hip bars and vibrant restaurants.

The group was organised. There were those tasked with grooming, there were runners and enforcers.

There were "friendly" estate agents who allowed access to properties where the gang's victims would be "pimped out" as sexual commodities for their abusers' financial gain.

Victim: "I was scared to say no"

The younger gang members would linger outside shops and parks chatting to the girls as they passed.

Many from dysfunctional homes, these children would be treated like grown-ups, supplied with drugs and alcohol and, as one judge said, provided with a "sense of belonging, a sense of esteem".

Such was the gang's hold over its victims, when one of the girls was left naked and abandoned after a gang rape, it was one of her abusers she phoned for help, not her social worker or the police.

Some of the girls contracted sexually transmitted infections and became pregnant - or both - with one 12-year-old girl, who was branded with the initial of a man who claimed to "own her", being made to have a back-room abortion.

Anjum Dogar and Mohammed Karrar were sentenced again in 2018, five years after receiving life terms

One 15-year-old victim, raped by gang ringleader Anjum Dogar and the case's most prolific offender Mohammed Karrar in 2004, told the BBC she had an abortion and did not know who the baby's father was.

Mr Morton said the men's victims went from "one minute believing in Father Christmas and the Easter bunny and the next they are being sold" for sex.

Unemployed Karrar would spend his days with his wife at his parents' house in Cowley and his nights with his girlfriend - when he was not carrying out horrific acts of child abuse.

In 2005, he had two children by the two women, born less than two weeks apart.

Dogar and his brother Akhtar, who "ruled the Cowley Road", were the ringleaders of the grooming gang and, according to the victims, the other gang members were scared of them.

Simon Morton's final case resulted in the jailing of seven men at the Old Bailey in 2013

The question for detectives was, if none of the girls would co-operate with social services and the police after they had been reported missing, how could their abusers be stopped?

In Rotherham and Rochdale, similar grooming gangs were coming to light. Mr Morton visited the investigation team in Rotherham, swapping notes.

One tactic Mr Morton's team used was to get consent from the parents of some victims to take the girls' underwear to be tested for DNA, to try to establish who was sexually abusing them.

"We didn't start with any victims. No-one came forward... we had to find the victims and then find the offenders," Mr Morton said.

"Normally we deal with things that are told to us, not things that aren't told to us."

'My life has been destroyed'

In a statement read at the sentencing of the final three defendants last month, Oxford Crown Court heard how one victim turned to crack cocaine to deal with the trauma she had experienced, which led her to a "life of crime" to fund her habit.

She said: "I struggle to live a normal life day to day. I still have a fear of going outside. I feel my life has been taken away from me.

"My life has been destroyed. I cannot form loving or lasting relationships with men. I have not been able to care for my children as a mother should be able to."

The abuse survivor, now an adult, said for many years she never told anyone what had happened to her because she felt "scared and embarrassed".

"This has ruined my chances of a normal life."

The team checked missing persons files, care home, hospital and truancy records. Detectives managed to track down one woman who told officers she had been abused as a teenager.

"I realised it was the same blokes she was talking about from six years earlier and it was then I realised the extent of the offending," Mr Morton said.

"We were able to make the leap between the years and the fact they were so organised as a crime group. I was able to show it spanned all those years."

After the first trial in 2013, seven men were jailed for crimes against six girls. Over the following years, men accused of similar crimes in Rochdale, Rotherham, Manchester and Newcastle would go on trial.

The same day the first group of Oxford abusers was sentenced, 27 June 2013, Mr Morton retired from the force.

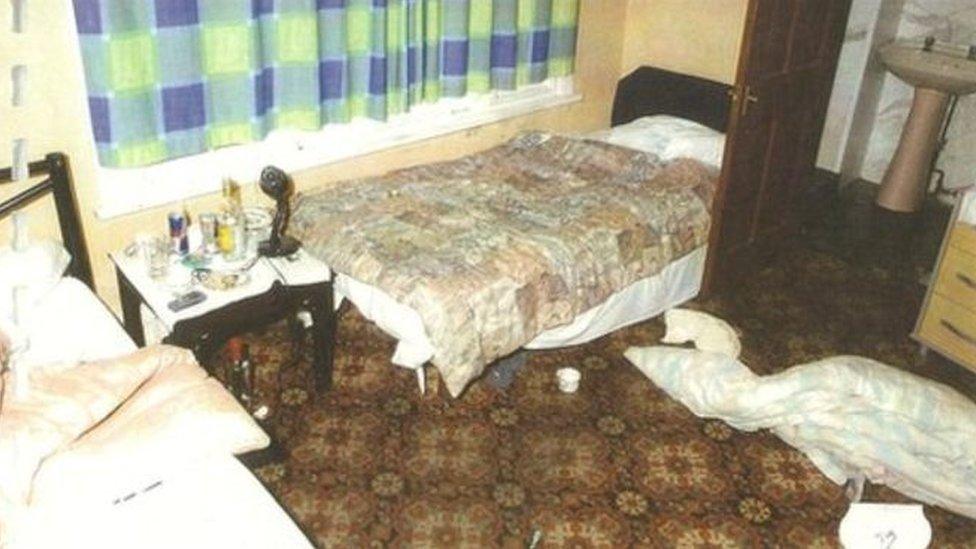

One of the premises used by the gang to abuse girls was the Nanford Guest House in Oxford

The scale of the abuse was not reflected in the cases that came to court - a serious case review published in 2015 found as many as 373 children, including 50 boys, might have been targeted in Oxfordshire over a 16-year period.

The review found "many errors" were made across the Thames Valley force and social services, both of which "failed to see that these children were being groomed in an organised way by groups of men".

At the time, Mr Morton said there was "no hiding" from these failures, adding that "in some aspects, calls for help were ignored".

Despite the lengthy prison sentences given to the seven men who were convicted in 2013, Det Ch Insp Mark Glover - who replaced Mr Morton as Operation Bullfinch's lead detective - knew "there was still a lot more work to do" investigating crimes that pre-dated those that were the focus of that trial.

Mr Glover's colleague Det Insp Nicola Douglas said "it was almost like forming a queue" in bringing further cases to court.

She said police had to be "really honest" with the victims, who could not "expect quick justice".

Mark Glover and Nicola Douglas worked on the Bullfinch investigation following the first trial in 2013

She said victims they approached would often say "this girl called so-and-so was at the party" and provide the nicknames of the suspects.

"Immediately, we knew this was Bullfinch-related. It was all the same names - they were names victims habitually spoke about."

Due to the time that had passed, there was no CCTV evidence, nor were there social media or smartphone records to analyse.

"It was about getting outside, tracking people down, finding all the records," said Mr Glover.

Many of the victims who were identified did not want to give evidence.

"We were knocking on people's doors, maybe professional people, who were married with families, and just the knocking on the door and saying, 'we're from Bullfinch'... it brings it all back to them," Mr Glover said.

He said he believed his team approached between 250 and 300 women. About a dozen would give evidence over the five trials that followed the first court case.

"I didn't know who the baby's father was"

Senior crown prosecutor Clare Tucker said the cases were built on "a number of girls giving evidence of a similar nature about one particular man".

"It was putting together a set of circumstances that the jury could comfortably be sure was believable and that was what had happened," she said.

The prosecutor, who prepared the case files for every trial, said evidence of how girls had been "groomed over the years" was key to showing "they weren't really consenting, they were submitting".

For Mr Morton, the investigation his team started has changed policing forever.

"There's a crime category [child sexual exploitation] that in the past hadn't existed and all of sudden, once you realise that there's all this abuse going on in every city and nearly every town, it makes you realise how many victims there are out there - how many young girls are being picked off the street and turned into something they're not."

Mr Glover, who retired in 2018 but returned to Thames Valley Police as a civilian investigator, accepts that the end of Operation Bullfinch is not the conclusion of this harrowing story.

"There are a lot of men who have escaped justice," he said.

"There's a lot of males out there who must be sweating a little bit because they know that we know."

If you've been affected by any of the issues in this story, you can find help here.

- Published14 May 2013

- Published13 February 2020

- Published21 January 2019

- Published12 June 2018

- Published16 April 2018

- Published21 September 2016

- Published8 July 2016

- Published7 March 2015

- Published4 June 2014

- Published27 June 2013