'Lost' baby ashes: How has it happened?

- Published

Campaign group Action for Ashes called for an inquiry into Emstrey crematorium in Shropshire

A report has criticised a crematorium in Shropshire for failing to give bereaved parents the ashes of their babies. How often does this happen, and why?

At least 60 families are believed to have been affected by failures at Shropshire's Emstrey crematorium between 1996 and 2012, which led to parents not being given the remains of their babies.

Research by the BBC suggests the return of baby ashes is routine in some parts of the country, but not others.

Over a five-year period, crematoriums across the UK did not return the ashes of more than 1,000 babies to their parents.

Sands, a national charity that supports those affected by the death of a baby, is campaigning for all parents to be given the option to receive their babies' ashes.

"There's a huge hole if parents don't have ashes because they don't have a special place they can go and be with their baby," Judith Abela, director of operations, said.

"They don't have that natural outlet for grief, to actually go and visit the baby on an anniversary, or their birthday, or at Christmas."

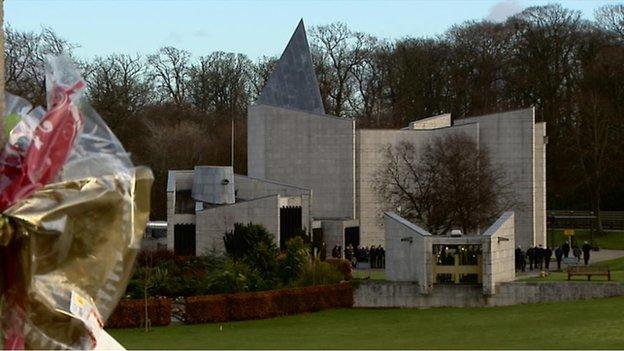

The practice of burying baby ashes in secret at Mortonhall crematorium went on for more than 40 years

The investigation into Emstrey crematorium follows a similar investigation into Mortonhall Crematorium in Edinburgh.

Parents in Scotland were told there were no ashes left when young babies were cremated, and crematorium staff buried baby ashes in secret for decades.

The inquiry found parents were not told as managers believed it would have been "too distressing" for them.

Any ash found after the cremations "would be mixed in with the first adult cremation in the morning," it said.

Following the Mortonhall report, the Infant Cremation Commission recommended new laws and guidelines to protect bereaved families.

Improved technology

Rick Powell, from the Federation of Burial and Cremation Authorities (FBCA), said the Scottish reports were a "wake-up call" for crematoriums.

"The Emstrey report is historic rather than current," he said.

"The situation they are referring to isn't necessarily the case now."

The FBCA code of practice requires crematoriums to recover ashes whenever possible.

Recovering those of a baby is potentially more difficult than recovering those of an adult as there are less remains, and these may become airborne within the cremation chamber and therefore lost under normal cremation conditions.

But Mr Powell said improved technology has made it possible for remains to be recovered in more cases.

"It's quite a different process when you are carrying out a cremation of a small infant, rather than a grown-up person," he said.

"Baby cremation runs at a lower temperature with more control over the turbulence, that's air added to the cremation chamber to help with the process."

Modern cremators have software programmes so the turbulence and heat can be better controlled.

"Baby trays" can also be put under coffins so that the remains can be collected more easily.

At least 60 families are believed to have been affected by failures at Shropshire's Emstrey crematorium between 1996 and 2012

Emstrey has returned ashes from all infant cremations since January 2013, after new equipment was installed and different cremation techniques were adopted.

David Jenkins, who led the Emstrey inquiry, has recommended the government appoint an independent inspector to oversee standards across England.

Meanwhile, Sands has written to every hospital trust in England and Wales, funeral directors and all the organisations that run crematoria, in an attempt to make standards consistent everywhere.

"The biggest issue is that there is no definition about what constitutes ashes, so it has led some authorities to say no ashes are left at the end of the process, because they don't contain human remains," Ms Abela said.

"Other authorities say whatever is left is valid remains, whether it's remains of the coffin or if there's a cuddly toy.

"What we want is for parents to be offered the choice, so that if they can be offered some ashes, regardless of whether it contains some remains, then they should be."

- Published1 June 2015

- Published7 April 2015

- Published7 March 2015

- Published10 February 2015

- Published30 April 2014

- Published9 December 2014