Aspen tree beaver attacks replicated in seed growing bid

- Published

A Shropshire tree company hopes an experiment will produce more aspen seeds

For Springwatch I'm looking at the work of Shropshire company Forestart, who gather the seeds of native trees from all over the country to sell on to nurseries for them to grow into new plants.

You might assume trees tend to produce their seeds in the autumn, season of mellow fruitfulness and all that.

But in fact some trees choose to produce and drop seeds much earlier in the year, in the spring. Most notably the willow and the less familiar aspen.

These are usually solitary trees and their Latin name Populus tremula gives a clue to their appearance.

They have leaves that flutter and tremble in the breeze in a way which looks a bit like a wagging tongue.

Indeed some people call them wagging tongue trees, or even mother-in-law tongue trees.

Clones not seeds

The teams at Forestart travel the country collecting seeds from all sorts of trees

But aspen present a bit of a problem for a company like Forestart.

The company aim to gather seeds from all sorts of different aspens from all over the country, then grow a nursery of trees that can interbreed and so produce stronger, more genetically diverse saplings in the future.

Trees that have more chance of being resistant to diseases that are arriving here in the UK thanks to imports, travel and a warming climate.

The problem with aspen is it isn't that bothered about producing seeds for much of its life.

Instead it sends up tiny suckers through the ground around the tree. Any of these could grow and become a new tree, genetically identical to the parent; a clone.

Much older trees do produce seeds, but given the solitary nature of the tree you end up with a potential seed supply scattered all over the country.

It's not very useful if your company's job is collecting seeds.

As a quick sidebar though, the fact these trees effectively clone themselves means when you see an aspen, it could well be the clone of a tree that's stood in roughly the same spot for hundreds, perhaps even thousands of years.

Certainly the one Rob Lees, from Forestart, showed me in a hedge near Ellesmere could have been around as far back as 1403, witnessing the nearby Battle of Shrewsbury.

Replicating beavers

Removing a strip of bark from the trunk simulates a beaver gnawing at the aspen, in the hope it produces a bumper crop of seeds

So cloning is useful for longevity, but rubbish for seeds.

The team at Forestart are trying an experiment to put aspens under stress to make them produce seeds.

Aspens like fairly wet conditions and one thought is at some point in their history they would have shared the landscape with beaver populations.

The beavers would level trees around the aspen and also have a good go at the bark of the aspen themselves. This creates stress, which produces seeds to take advantage of the newly cleared ground.

We spent a pleasant afternoon in the sunshine replicating the effect of a beaver on a small group of aspen trees.

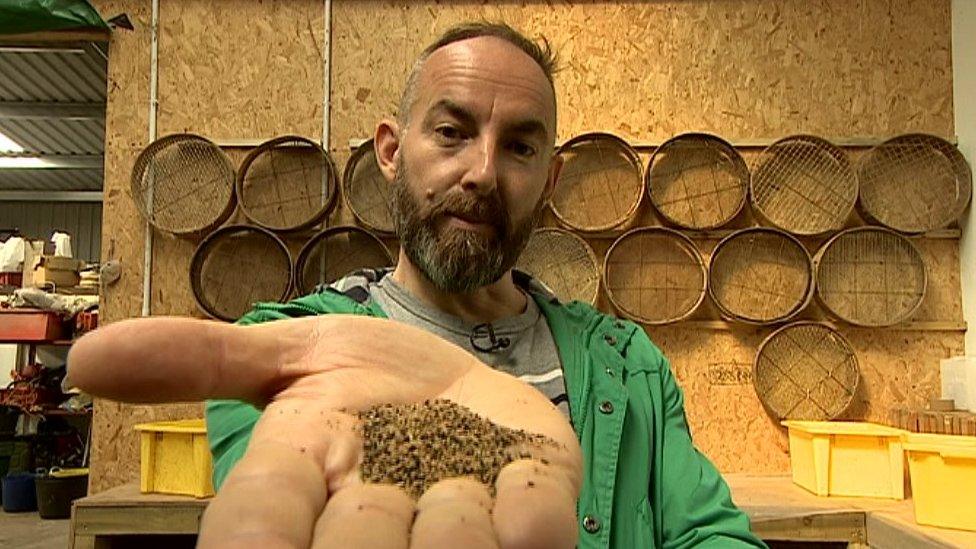

The tiny golden grains are in fact the seeds of the aspen tree

Unlike the beaver and, for the sake of my teeth, we chose to use a small saw and chisel to strip out a line of bark almost circling the tree trunk.

The idea is the nutrients produced by the leaves will mostly be trapped above the line we removed and that will produce a bumper crop of seeds.

We'll find out in 12 months' time if this group of aspens, which have only flowered once in more than 20 years, have taken a turn for the seed producing.

For Forestart though, this is the start of seed season.

They will follow the aspen and willow seeds up the country as they come into seed over the next few weeks.

Then it's on to the native cherry and so it goes throughout the year right into autumn.