Discover the violent end of the Oxford dodo

- Published

A dodo model on display in Oxford - the actual dodo remains are usually kept under lock and key

For a bird that has been extinct for more than 350 years, you probably think there is not much left to learn about the dodo. But you would be wrong, thanks to the latest research at the University of Warwick.

The specimen that the team based at WMG, external has been studying is a very famous dodo indeed. It belongs to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, external and it is so precious it is kept under lock and key.

From a scientific point of view it is interesting, external because what the museum has is a mummified foot and head. It is our most complete set of remains of a single dodo left in existence and the only dodo soft tissue to be found anywhere - and soft tissue can be used for DNA analysis.

These are the best preserved remains of the dodo anywhere in the world

But it is also a literary dodo, external. This specimen fascinated Charles Dodgson (perhaps better known as Lewis Carroll) and also illustrator John Tenniel. Carroll would write the dodo into his book Alice in Wonderland and Tenniel would add his famous illustrations of the bird.

Killed by humans

Finally, of course, this dodo is also a symbol. A symbol of the terrible impact humanity can have on our environment. These large flightless birds lived happily on Mauritius until Dutch explorers arrived in 1598. Just over 150 years later they were extinct. Killed by humans, or more accurately by the rats and cats we brought with us that ate the young and the dodo eggs.

Oh yes, it was not hungry sailors who did for the plump dodo, contrary to popular opinion. In fact, the dodo was not even that plump - that is a misconception based on observations of fat, captive specimens and poorly stuffed dead ones.

There is a great article on the BBC website discussing the treatment of the science of the dodo after they were wiped out and it makes pretty grim reading. If nothing else it explains why our best dodo specimen is just a foot and a head.

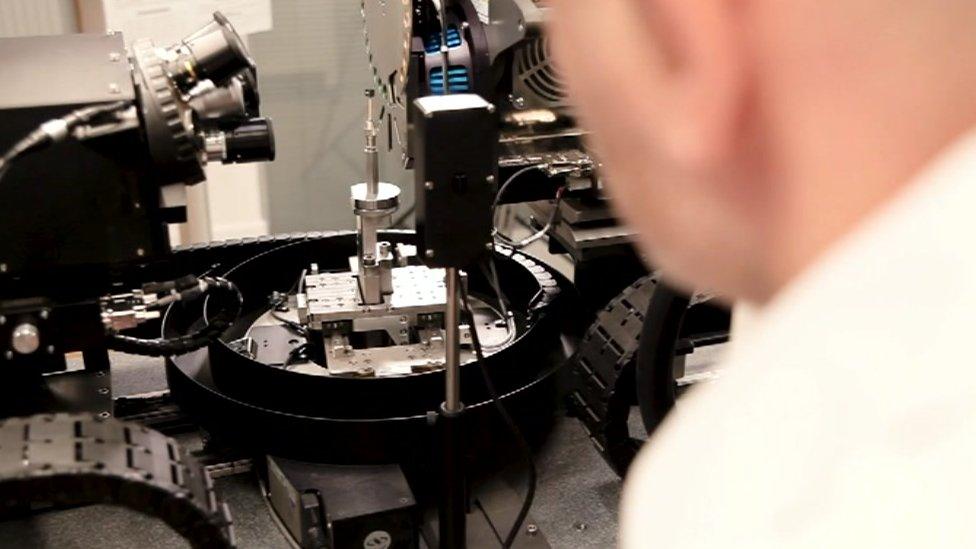

The University of Warwick has used the latest technology to scan the mummified dodo remains

A chance to put the Oxford dodo into the state-of-the-art scanners at WMG at Warwick University was not just an amazing opportunity, it was also a chance to right a historical scientific wrong - to treat the sad story of the demise of the dodo with a bit more respect this time around.

Higher power

Because the dodo is dead, the scanners the team was using could be cranked up to a higher power and better resolution than if they were being used on living tissue. The result is our most comprehensive look yet at this distant relative of the pigeon.

Bird brain

First and most shocking discovery? We know what killed the Oxford dodo. Often assumed to be a captive specimen that probably died of ill treatment or disease rather than old age, it turns out the bird was actually shot in the back of the head and the neck. A number of lead shot pellets, typically used to hunt wildfowl during the 17th century, were found by the team.

Next, it might even be possible to tell which country produced the shot that actually killed the Oxford dodo.

The team also seems to be hinting at other discoveries yet to be announced. Perhaps finally after centuries of neglect, the dodo is getting the attention and respect it really deserves.