Shropshire baby deaths review: What do we know?

- Published

Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust was placed in special measures in November 2018

Two troubled hospitals are at the centre of a baby deaths scandal dating back more than 40 years.

Hundreds of cases are being looked at, amid a review into claims children, and mothers, died or were permanently harmed by care failures at Telford's Princess Royal and the Royal Shrewsbury hospitals.

Although not all the cases relate to deaths or serious harm, many are alleging significant errors, according to the BBC's Michael Buchanan.

What has happened so far?

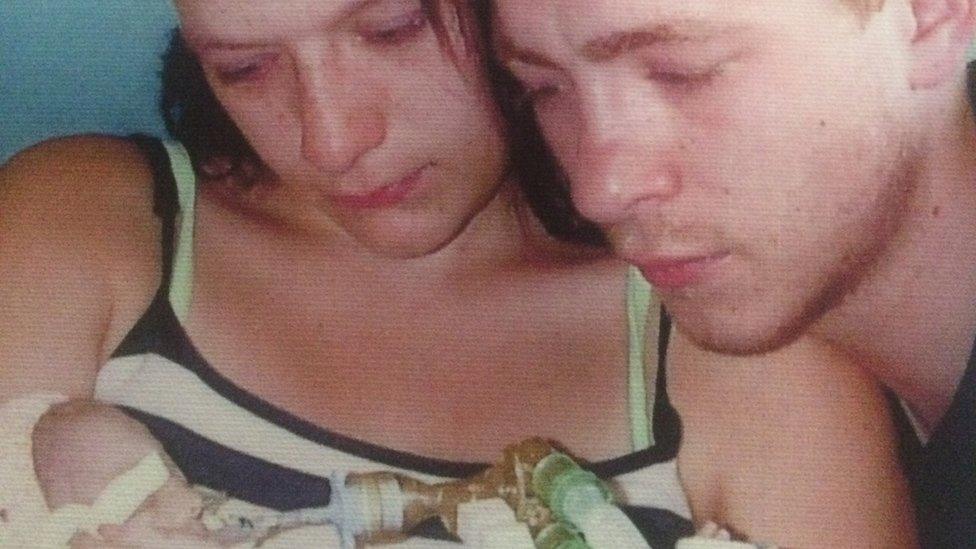

Tasha Turner and partner Jacob's baby Esmai died in 2013 at the Royal Shrewsbury Hospital

In April 2017, then Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt announced an investigation into a "cluster" of avoidable baby deaths at the Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust, which runs both hospitals.

The review was initially focused on 23 cases in which maternity failings were alleged.

In August 2018, its scope was expanded to look at 40 cases between 1998 and 2017, then later to 100.

The figure has now grown to more than 1,000, covering the period from 1979 to the present day.

The trust said it was co-operating fully with the review, which is being led by midwife Donna Ockenden. Its findings are expected to be published by the end of 2020.

Dr Bill Kirkup, who led the inquiry into the Morecambe Bay scandal, says the details revealed so far in Shrewsbury and Telford suggests the failures might be more widespread in the NHS.

How did babies die?

Jack Burn died hours after being born at Princess Royal Hospital in Telford

In some cases, which have previously been reported, failures to properly monitor foetal heart rates and delays in deliveries were found to have contributed.

Out of seven avoidable deaths between September 2014 and May 2016, failure to properly monitor heart rates was found to be a contributory factor in five, the BBC discovered.

One such case involved Kelly Jones, whose twin girls were stillborn at the Royal Shrewsbury in 2014.

She said she had been ignored by staff despite repeatedly telling them she felt pain during pregnancy.

The trust admitted her daughters' deaths from oxygen starvation to the brain had been contributed to by "delay in recognising deterioration in the foetal heart traces and the missed opportunities for earlier delivery".

A further report found the 2009 death of Kate Stanton-Davies at six hours old could also have been avoided after warnings of potential complications were missed.

The trust said it had "failed to meet the high standards we set for all of our patients".

It has since paid out millions of pounds in compensation to families of babies born with brain injuries.

One firm handling claims said it was "repeatedly seeing the same errors - failures in relation to heart trace monitoring and realising the baby is in distress, delays in taking women for an emergency caesarean and issues with the wrong use of forceps".

A leaked interim report has also described some of the experiences of families, including babies left brain-damaged because staff failed to realise labour was going wrong, staff getting the names of some dead babies wrong and, in one case, referring to a child as "it".

What are the other problems?

The inquiry's initial scope was to examine 23 cases but this has now grown to more than 1,000, covering the period from 1979 to the present day

As well as the midwife-led, independent review into alleged maternity errors, the trust in charge of both hospitals has also been placed in special measures, in part due to its maternity units.

It has faced criticism from the Care Quality Commission (CQC), whose inspectors assess the standard of services provided by a hospital. However, a CQC visit in November 2019 found maternity staffing had increased and morale and governance had improved.

Back in October 2018, inspectors were so alarmed by what they saw on the trust's maternity and emergency wards in Shropshire they ordered bosses to submit weekly status reports.

A few weeks later, the trust received its third CQC warning in four months - highlighting staffing concerns in certain critical care and emergency areas.

Two days after that, the trust was placed in special measures - meaning it was no longer trusted to run itself alone.

Unusually, the decision was taken by health service bosses before the CQC had made a recommendation to do so.

NHS Improvement said it had identified a number of "challenges" which could threaten patient safety, including governance, staffing, urgent and maternity care and whistle-blowing issues.

The CQC said it would have been likely to recommend special measures, as it believed the trust would be unable to improve "without external support".

In May 2019, "further urgent action" was taken by the CQC, amid safety concerns over emergency and maternity services.

What's the next step?

Donna Ockenden's findings are expected to be published by the end of 2020

The trust will receive "enhanced support", including additional funding, while in special measures, NHS Improvement said.

The trust is usually re-inspected by the CQC within 12 months of going into special measures, but this can be sooner if there are "significant concerns about quality", or if there is "enough evidence of good progress", the watchdog said.

If inspectors feel a trust has made enough progress, they will recommend it is taken out of special measures.

Where there has been insufficient progress, the CQC will consult with NHS Improvement to decide whether further action is needed.

At the release of the leaked report, Ms Ockenden said families had told her they wanted one, single, comprehensive independent report covering all known cases of potentially serious concern within maternity services at the trust, with she and her review team working hard to achieve this.

There is another factor. In June 2020, West Mercia Police confirmed it was exploring whether to bring a criminal case against either the trust or staff in connection with maternity care.

As it investigated whether there was evidence to begin proceedings, the force encouraged anyone with information to make contact.

- Published30 June 2020

- Published14 November 2018

- Published8 November 2018

- Published5 October 2018

- Published6 September 2018

- Published13 April 2017

- Published12 April 2017