Inside Ironbridge Power Station's doomed cooling towers

- Published

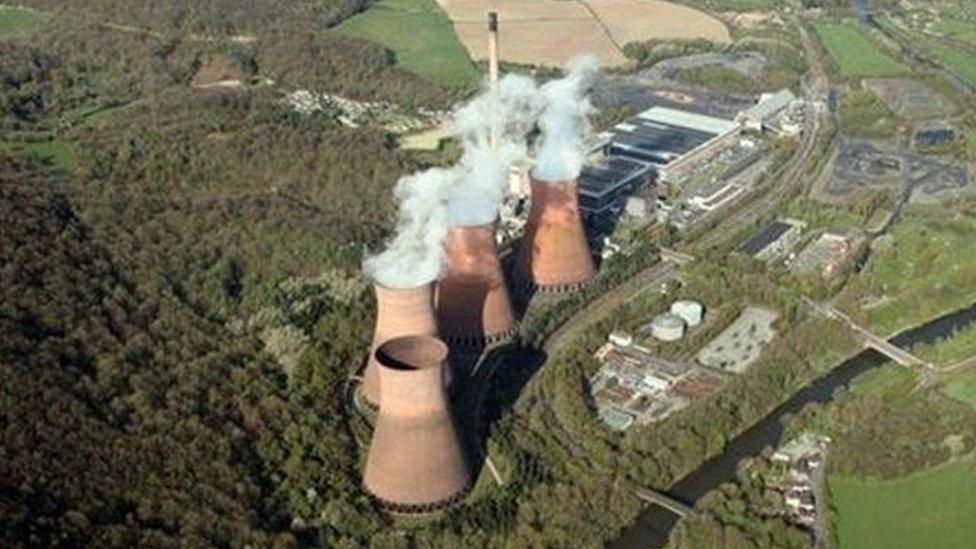

Ironbridge Power Station dominates the horizon in the Ironbridge Gorge

For 50 years now, they have stood proudly at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge as one of Shropshire's best-known landmarks. But the cooling towers at Ironbridge Power Station will become just a memory later this year - when they are demolished simultaneously in a matter of seconds.

The power station opened in 1969, but stopped generating electricity in November 2015. Now a major programme of demolition is under way at the site, nestling on the banks of the River Severn.

It's nearly five years since the cooling towers were in operational use

The dramatic moment will be the collapsing of the four cooling towers. And although no firm date has been announced, developers Harworth Group said they were committed to bringing them down "later this year".

Preparation work for the demolition has been under way since the summer

A circle of light at the top of tower two

It is a date in Ironbridge's history that is likely to draw large crowds to the area. Already photographers and fans of the towers have been scouting out the best positions to position their cameras and tripods.

For now, a team of demolition workers continue working to transform what was once one of the UK's largest plants, providing power for the equivalent of 750,000 homes.

A huge recycling scheme will take place after demolition

The most recent master-plan shows a mixed-use scheme for 1,000 new homes in addition to a range of commercial, leisure and community uses, including a park and ride facility and a school.

Talks have been taking place with Network Rail over bringing existing rail sidings on the site back to life.

The countdown is on to demolition, with the developers awaiting final permission from Shropshire Council

Walking around the site, you are immediately struck by the imposing size of the towers, and the bravery and skill of the workers who built them.

And it is pretty awe-inspiring to step inside one of the towers, where air and water were once brought into direct contact with each other to reduce the water's temperature.

Next door to the towers is the cavernous turbine hall, where you could be forgiven for thinking you have wandered on to the set of a Mad Max sci-fi film.

The giant turbine hall helped deliver power for up to 750,000 homes

It is a mass of mangled metal and giant tubes, with workmen using oxy-acetylene cutting equipment.

The demolition work is due to take 27 months to complete

Machinery parts await removal from the turbine hall

Large pieces of machinery are taken apart with oxy-acetylene cutting equipment

Building work on the power station began in 1962, and it was connected to the National Grid seven years later.

Originally coal-fired, it converted to burning wood-pellets in 2013.

The power station was switched off when it reached its 20,000 hours limit of generation under an EU directive.

The four towers sit on the banks of the River Severn

A familiar Shropshire view - but not for much longer

You may also be interested in:

Nearby residents were divided over whether they wanted to see the demise of the cooling towers, with some saying they were "an eyesore".

But others had been clinging to the hope that at least one tower could be preserved for generations to come.

Photography and words by John Bray

- Published2 July 2019

- Published1 July 2019

- Published19 July 2018

- Published19 June 2018

- Published9 November 2017