Covid 19: Increase in parents abused by children in lockdown

- Published

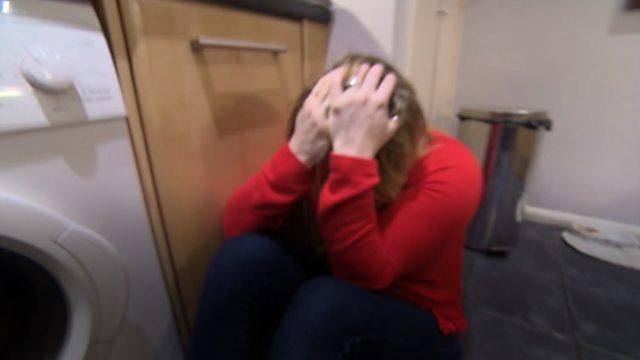

Parents have reported suffering physical and verbal attacks by their children - and many witnessed a rise during lockdown

More than 300 parents who say they are being abused by their own children have sought help from a support group set up at the start of lockdown.

Violent outbursts, verbal attacks and even cases of sexual abuse have been reported by families to Shropshire-based Parental Education Growth Support (PEGS).

Director Michelle John said child to parent abuse was "misunderstood and very much hidden".

"Parents are struggling to be heard and they're living in fear," she said.

In August, a report from the Universities of Oxford and Manchester said 70% of parents who had previously experienced child to parent violence, external reported attacks worsening when the UK went into lockdown in March.

More than two thirds of social workers also said more episodes were reported to them as the support network around families disintegrated.

'I have been hit with metal belt buckles'

Sandra says police have been to her house more than 20 times - but she still feels like no one can help her

Sandra has been abused by her daughter since she turned 12, just over two years ago.

"I think back at the beginning it was probably just a little push or shove and then progressed to more direct hitting," she said.

"I have been hit with metal belt buckles, I have had knives pulled out on me - although they've not been used.

"I've been bitten, lots of scratches, bruises, punches, hair pulled out. I've had scarves pulled tight around my neck in a choking fashion, lots of kicking. And that is just the physical abuse, there is obviously a lot of psychological and emotional abuse that goes along with that."

Sandra says she kept quiet about the attacks for a long time because she wanted to protect her daughter's reputation, and because she found it "humiliating". But eventually she felt she had no choice but to call the police, estimating she's had to do this at least 20 times.

"The last thing I want is for my child to be criminalised especially as she is now getting to an age where she will be of criminal responsibility. But I am frightened. I am frightened of being so badly hurt that I can't protect my younger child in the house.

"Even when you do call the police they are very sympathetic, very understanding but they fill in reports and nothing happens. It is up to social services whether any action is taken.

"I think because I'm not a drug user, I'm not an alcoholic and we don't live in poverty, there isn't that much help offered and any help in the past seems to be directed towards me making changes so me changing my parenting beliefs or values."

PEGS, which helps families across the country, was started by Ms John in March after her research found families had very few places to turn.

It provides tailored support to each case - anything from ensuring homes are as safe as possible with dangerous objects hidden to contacting police forces so they're aware of the seriousness of situations.

They also identify services near to where families live and offer training in how to deal with escalating situations.

"Parents are reluctant to come forward and perhaps they don't realise this is domestic abuse," she said.

"Practitioners aren't even considering that domestic abuse can happen in families where the child or young person is displaying these violent behaviours towards their parent.

"It's really sad what we do. We're regularly seeing parents contacting us saying they're scared and frightened of their child because their child is physically harming them, whether that's punching or kicking them. Quite a few have mentioned their child has made threats to kill."

'The fear of her killing me was real'

Louise had to make the heartbreaking decision for her daughter to live away from the family home because she feared for her life

Louise was so terrified of her teenage daughter's violent outbursts she had to barricade herself in her bedroom. Her daughter is now living elsewhere.

"[She started] trashing the house, setting fire to her room, harming her brother and the police become part of our routine," she said.

"I had to give up work as she was absconding from school or just not going and the school, despite knowing the abusive behaviours at home, were going to look at fining me for her non-attendance - this just added to more stress and worry.

"I repeatedly asked for help [but] we were told that there were no safeguarding concerns or unless my child wanted to engage or ask for help there was nothing anyone can do and that we were to just get on with it."

The girl was eventually arrested but when her mother tried to arrange alternative accommodation for her daughter, she says her local authority threatened to prosecute her for child abandonment. Her daughter returned home but the attacks started again.

"I had to barricade my bedroom as the fear of her acting out and killing me was real. If my partner had acted this way I would have been offered support and not ignored.

"My daughter is not living with us anymore and the risk of harm is still there, her behaviour has become more controlling and coercive rather than the physical attacks."

"We've grown a lot quicker that we anticipated," said Ms John.

"There's very little support out there for parents. What people have said to us is that they finally feel heard and not judged. We've seen parents become more empowered and more assertive in asking for help.

"What I would say to parents is if their child is abusive to them and they are living in fear, then they should access support as soon as possible.

"You are not alone, and it's not your fault."

* Names of family members and some identifying details have been changed to protect identities. For more information on organisations that can help if you are experiencing domestic abuse, visit BBC Action Line. PEGS can be contacted via this website., external

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published7 August 2019

- Published23 April 2020