Thousands of bodies under Bath Abbey threaten its stability

- Published

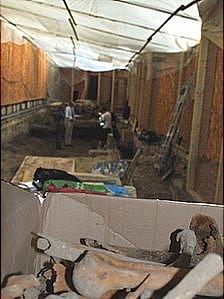

BBC reporter Jon Kay: "Over the centuries, thousands of bodies have been buried underneath the Abbey"

For more than 300 years, thousands of people have been buried just below the stone flooring of Bath Abbey.

It is estimated that up to 6,000 bodies have been "jammed in" to shallow graves under the church's grave ledger stones.

Now as the floor of the 500-year-old building begins to lift and collapse, the abbey has discovered "huge great voids everywhere" beneath its flooring.

"It's where previous burials and graves have settled down and left voids," said Charles Curnook, from the abbey.

"We were quite surprised the floor hadn't collapsed already on us."

Bath Abbey, which dates back to 1499, sits on the remains of a massive Norman cathedral.

Three different churches have occupied the site and since the early 1500s, thousands of people have been buried under the building.

More than 10 boxes of human remains have been carefully removed

"There were burials here all the way through to about 1840," said Mr Curnook.

"But at that point the place was full and they opened the Victorian cemetery at Ralph Allen Drive and stopped burying people here.

"I've had lots of estimates of how many bodies are buried here, but somewhere between 4,000 and 6,000, but they just jammed them in and jammed them in - it would have been very unpleasant to put it mildly."

But it was not until trial digs at the beginning of 2011 and 2012 that the effect the bodies were having on the long-term stability of the building was discovered.

"We were looking for the foundation walls of the Norman cathedral on which we could lay a new floor," said Mr Curnook.

"But we didn't find any - what we found instead were huge great voids underground in every place.

"And when we went in underneath one of the medieval pillars there was fresh air underneath it, at which point we stopped work."

'Most shocking'

The honeycomb of huge voids, created by burials shifting and decaying, was a problem the Victorians had also discovered more than 100 years earlier.

But under Sir George Gilbert Scott, who from 1864 to 1874 completely transformed the inside of the abbey, it was a problem that had been tackled in the "most shocking" way, according to Mr Curnook.

"They basically churned up the graves that were there and broke them up to try and consolidate the floor," he said.

"They were very much more robust than we are - the burials had not been in the ground for more than 30 or 40 years."

Now a century and a half later the abbey is again lifting every bit of furniture in the place as well as its huge grave ledger stones in an effort to stabilise the ground underneath.

And, as part of its ambitious £18m Footprint project, it is also planning to install new under-floor heating which taps into the city's hot springs.

'Say a prayer'

With the "weak concrete slab" laid by the Victorians removed, contractors are now clearing wheel barrow loads of earth ready to "drill down" to the fairly stable Norman cathedral floor on the hunt for more voids.

"We're going through the earth where there are burials but we're not going anywhere near any intact burials but obviously we are finding human remains," said Mr Curnook.

Once the voids have been filled the human remains will be reinterred

"And wherever there are voids found we'll be pouring grouting into them to fill the floor up to stabilise it.

"We'll then bring the same earth back in again and any human remains we've found we'll carefully reinter those bones and say a prayer over them."

So far more than 10 cardboard boxes of human remains have been carefully put to one side, ready to be returned along with bits of coffin handles, inscribed plaques and lead-coffin lining.

But, according to Kim Watkins, the archaeological consultant on the project, it is only disturbed graves that they are uncovering, with mainly adult bones dating from the early 1800s.

"The conditions here aren't good for the preservation of anything but there's no jewellery or coins unless they removed them in the 19th Century," she said.

"But it's the extent of the disturbance by the Victorians that more than anything has surprised me and unfortunately it's more the destruction that's a surprise than what has actually survived."

- Published13 July 2013

- Published13 March 2013

- Published24 July 2012

- Published22 March 2012

- Published31 January 2011