Young people 'feel anxiety and terror' using fitness apps

- Published

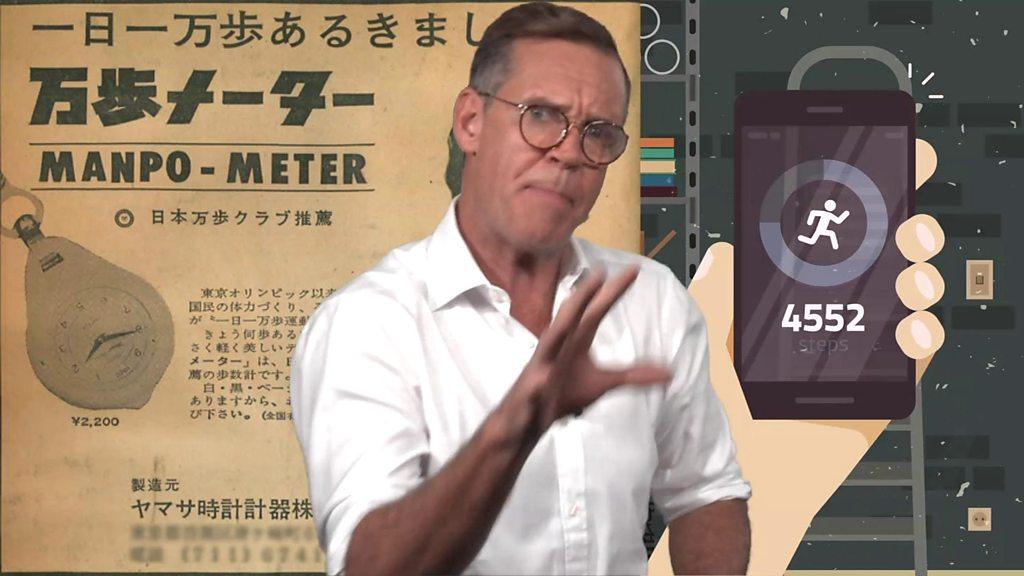

Use of fitness tracking technology has become commonplace among runners in recent years

Young people's use of phone apps to monitor and improve their health has led to "obsessive behaviour, anxiety and terror", a study has suggested.

The Digital Health Generation said children as young as eight were using the internet as part of their quest for fitness, a six pack or a thinner body.

It warned the use of fitness trackers, while "potentially motivating, could lead to obsessive behaviour".

Respondents also said the apps should identify when users needed to stop.

Jack Bardzil, 19, from Bath, said he could see how fitness trackers and apps could make people paranoid.

Jack Bardzil is now studying chemistry at UCL

"There are heartbeat monitors and in the future they might have glucose monitoring... these things can lead to paranoia," he said.

And he said the way social media sites sometimes promoted content based on users' previously-viewed material felt "upsetting.... [as] they can keep shoving it down your throat".

The survey noted the use of health and fitness apps, external could contribute to some young people over-exercising or engaging in harmful dietary practices.

More than 70% of young people, some as young as eight, are using apps and other digital online technologies to track and manage their health, according to the authors

One respondent, named Leif, said society judged people by their appearances and many went to great lengths to improve their physique.

"There's a fine line between going too far and developing an obsession," he said.

"I think, a lot of these fitness apps... you're not seeing the results you want to see instantly.

"I'll look in the mirror and be like 'Why am I not ripped yet?'."

Another respondent, Daphne, said she had become obsessed with an app that tracked her food intake and exercise and her sister had told her to delete it from her phone.

Many young people "lacked comprehension" of how their personal health data is stored or who can access it

Tom Madders, from the children and young people's mental health charity YoungMinds, said while fitness tracking could be a positive experience, when it became "all-consuming" this could cause negative consequences for mental health.

"For some young people, fitness trackers may exacerbate disordered eating and exercise, and it's important that they are designed in a way that minimises the risks - for example, by not bombarding people with notifications," he added.

Nearly half the participants said they struggled in finding accurate medical information online.

One respondent, Andrew, spoke of how easily searching symptoms online could lead to a "ridiculous" diagnosis that only made the person even more anxious.

He said, for example, typing in symptoms often produced an article wrongly suggesting "you've got cancer and you are going to die tomorrow".

"That kind of panic, I think, is pretty prevalent on the internet," he said.

"I think there are a lot of amateurs who think that they know a lot more than they actually do, and they're undoing all the work that the NHS is trying to do."

Prof Emma Rich, from the University of Bath's Department of Health, said the two-year study looked at how 1,019 people aged between 13 and 18 engaged with digital health via apps, social media, and the internet.

The research suggested as a result schools should expand their digital literacy lessons to include health matters.

Prof Rich said many participants used apps to to track their sleep, diet, heart rate and menstrual cycle, but often what the trackers said did not tally with how their bodies felt.

She was concerned people were constantly checking fitness trackers and worried the "gameification" of health apps led to obsessive behaviour in an attempt to get the most shares or likes from their peers.

"Many spoke of the need for health and fitness apps to come with warning alerts... advising them on when they might be exercising or dieting excessively."

And Elliot, 14, said: "I think if you're going to have a [fitness] app it needs to tell you when to stop, to stop you going too far."

The study was conducted by the universities of Bath, Salford and University of Canberra,

- Published27 April 2019

- Published20 September 2016

- Published23 November 2018

- Published13 January 2017