Dwarfism: Woman pens book to raise awareness of condition

- Published

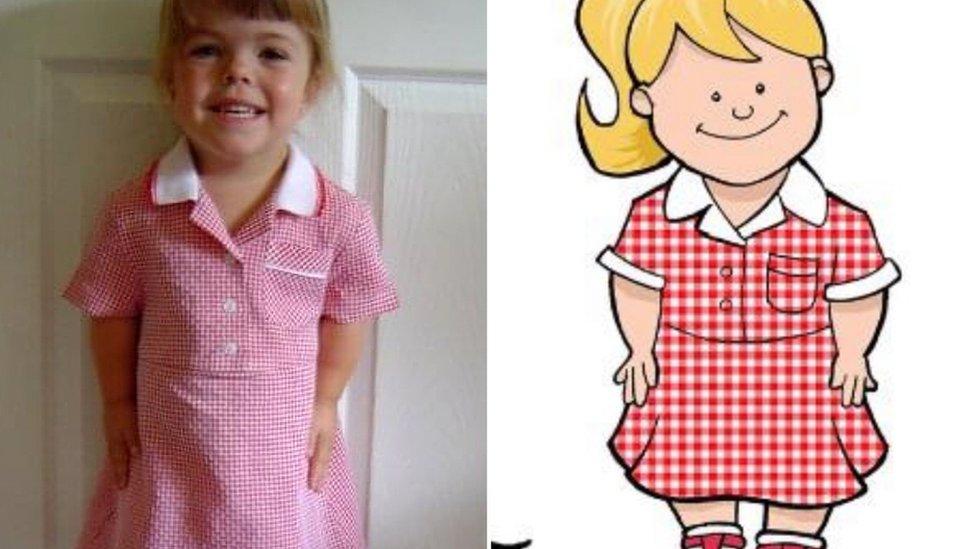

Danielle Webb said her book mirrors her childhood experiences of "making friends, watching those around me grow whilst I didn't"

A woman with dwarfism who wants parents to stop "pulling their curious children away" when they see her, has written a book to raise awareness about her condition.

At just under 4ft tall (121cm), 22-year-old Danielle Webb has a rare form of the restricted growth disorder.

Her book "Mummy there's a new girl" is about a boy who learns "size is no big deal" when a new girl joins his class.

Ms Webb said: "I wanted to answer the questions I commonly get asked."

She grew up in Portishead, near Bristol, in an average height family.

"I was the first one in my family to have my condition," she said.

"So I've grown up like everyone else doing everything my friends and older cousins did."

Ms Webb said the first time she met someone like her was when she was 13

It was at the age of about eight that she "really started to notice" she was the smallest in her class.

"I remember going home and telling my mum: "All my friends are growing and I'm not," she said.

"But by the time secondary school hit, there was no denying it. It was really obvious."

What is dwarfism?

There are two main types of dwarfism, also known as restricted growth, according to the NHS, external.

Proportionate short stature involves a general lack of growth in the body, arms and legs and is most commonly caused by being born to small parents, although it's sometimes the result of the body not producing enough growth hormone.

Disproportionate short stature, where the arms and legs are particularly short, is most commonly caused by a genetic condition called achondroplasia. Many children with achondroplasia have parents of normal height.

Ms Webb said she "didn't ever look like anyone" she saw when she was growing up and the first time she met someone like her was when she was 13 years old.

"I'm very open about it, I have dwarfism," she said.

"For me dwarfism just means I'm smaller than everyone else, nothing more."

She hopes her new book will remind people "to look past one another's differences".

She said she wrote her book, to help parents deal with the embarrassment of their children asking: "Mummy, why is she small?".

"The parents don't know the answer and that's when the panic starts to kick in, pulling the child away, crossing to the other side of the street, hoping that I haven't noticed," she said.

"But I can guarantee I've noticed. So you might as well allow your child to ask because you're probably causing more of a fuss by trying to hide it."

She hopes her new book will remind people "to look past one another's differences".

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published3 June 2021

- Published24 July 2014

- Published17 February 2013

- Published11 July 2011