The Forgotten Flood: Sheffield's tragic past remembered

- Published

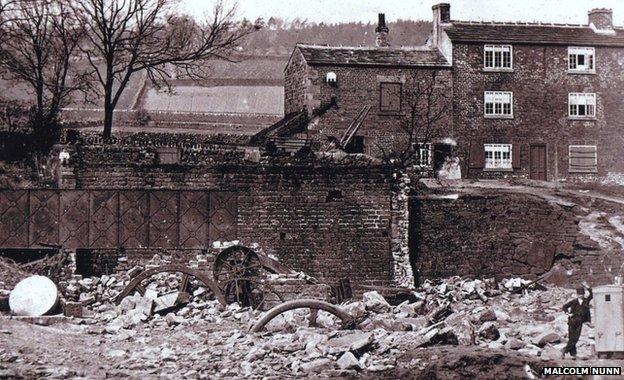

The flood devastated several communities in the Sheffield area, destroying some 43 mills

The Great Sheffield Flood of 1864 claimed the lives of at least 240 people and left more than 5,000 homes and businesses under water when the poorly constructed Dale Dyke Dam at Bradfield collapsed.

Shortly before midnight, on 11 March, more than 690 million gallons (3.14 billion litres) of water surged into the Loxley and Don Valleys and on towards the city.

As families slept, the raging torrent smashed into their homes, killing them instantly and washing away all but the faintest traces of scores of buildings.

The body of one victim was reportedly found 18 miles downstream of his home while, in Malin Bridge alone, 102 people were killed, including 11 members of one family.

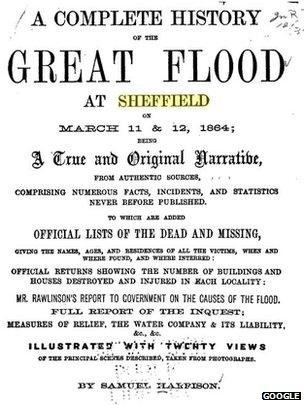

Journalist Samuel Harrison published his account of the flood

Peter Machan, author of The Sheffield Flood, said: "It was a major disaster. In terms of Victorian England it was the greatest disaster in terms of loss of life, apart from maritime disasters."

Despite the widespread devastation, the full detail may have been lost without the efforts of journalist Samuel Harrison to document the disaster and its aftermath.

The story of the Great Sheffield Flood is also little known outside of the city and the surrounding area.

Harrison's book "A Complete History of The Great Flood at Sheffield" provides a unique snapshot of life at the time of the flood and the unfolding events of 150 years ago.

He describes the events of March 1864 as "a calamity, appalling and almost unparalleled".

"An overwhelming flood swept down from an enormous reservoir at Bradfield, carrying away houses, mills, bridges, and manufactories, destroying property estimated at half a million sterling in value, and causing the loss of about two hundred and forty human lives", he wrote.

The dam at Bradfield Reservoir was breached shortly before midnight on 11 March, 1864

The Bradfield Reservoir was built between 1859 and 1864 by the Sheffield Waterworks Company to supply mills along the Loxley Valley and provide a limited supply of running water to Sheffield, about eight miles away.

The water, which was up to 90ft (27m) deep in places, was held back by the 500ft (152m) wide and 100ft (30m) high Dale Dyke Dam.

At about 17:30 GMT on 11 March, quarryman William Horsefield spotted a crack in the embankment "only about wide enough to admit a penknife" and alerted a number of local workmen.

By 19:00 the crack had widened to the width of a man's finger and a messenger was dispatched by horse to Sheffield to fetch the dam's engineer John Gunson.

Gunson arrived at the dam shortly after 22:00 and attempted to relieve pressure by blowing up the waste water weir, but was unsuccessful. Within two hours, the dam was breached.

Malcolm Nunn, Bradfield parish archivist and relative of William Horsefield, said: "It killed 240 in the night. That's the recorded figure but we've found through research there's perhaps about another 50 to 60 that died.

"It was a major disaster."

There was no gradual escape of water but a "sudden and overwhelming rush", wrote Harrison. The reservoir was empty within 47 minutes, he said, as water cascaded down the hillside at speeds of up to 18 mph (29 kmh).

A government inspector later remarked: "Not even a Derby horse could have carried the warning in time to have saved the people down in the valley."

In the following hours the settlements of Bradfield, Damflask, Little Matlock, Loxley, Malin Bridge, Owlerton, and many others, as well as the houses, farms, and mills in between, were swept away by the raging water.

In Sheffield the water was as deep as 4ft in places and in Rotherham one man reported seeing "trees, household furniture, pigs, massive beams and iron work" floating past.

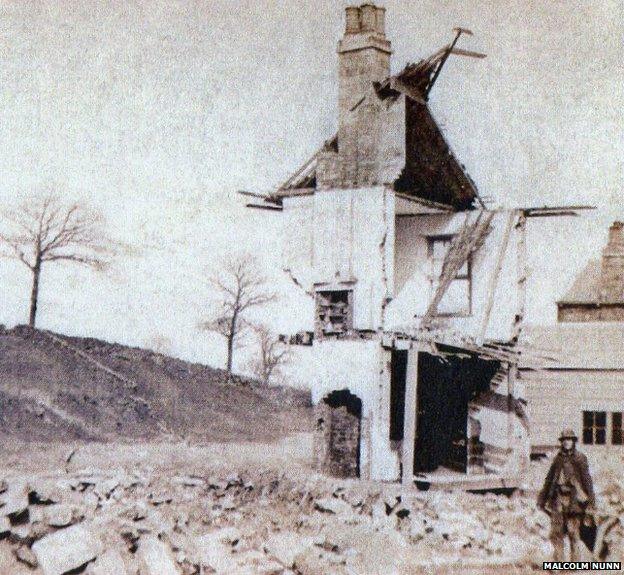

The shattered remains of the Cleakum Inn, rebuilt later as the Malin Bridge, is one of the many striking images of the disaster

Mr Machan said: "It was not just flooding, this was like some kind of great steam hammer battering into them so the buildings were absolutely smashed apart."

Describing the scene at Malin Bridge, Harrison wrote: "A bombardment with the newest and most powerful artillery could hardly have proved so destructive and could not possibly have been nearly so fatal to human life."

Of those killed by the raging flood, the youngest was just two days old and the eldest was aged 78.

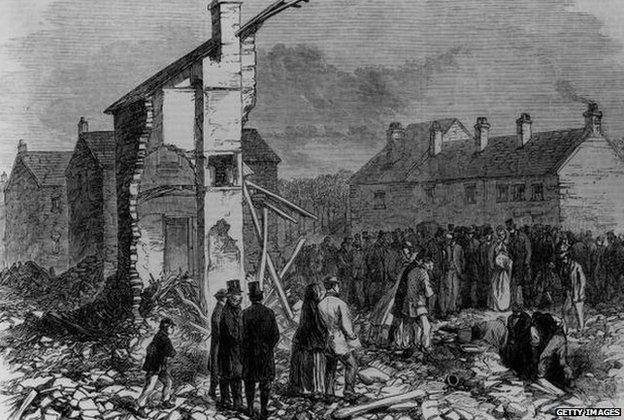

In the days after the disaster the area became a magnet for tourists eager to see the devastating effects of nature.

"The Loxley Valley was more like a fairground the following week," Mr Machan said.

"People sold hot chestnuts by the road side and extra trains were put on to bring people to the area."

More than 100 buildings were destroyed in the Great Sheffield Flood, including at Hill Bridge, where the bridge and five house were swept away

Huge crowds flocked to the Loxley Valley after the flood to see the scale of the devastation

A relief fund was set up to following the flood to help those affected and among the contributors was Queen Victoria, who sent a personal cheque for £200.

In October 1864 the government set up a board of inundation commissioners to deal with more than 7,000 compensation claims totalling more than £450,000.

A report by government inspectors pointed the finger of blame for the dam's collapse at Sheffield Waterworks Company and its engineers Mr Gunson and John Leather.

The jury at the inquest also returned a verdict citing a lack of "engineering skill and attention in the construction of the works, which their magnitude and importance demanded".

The exact cause of the dam's failure however was not uncovered until more than 100 years later when a study uncovered issues with the watertight barrier - or puddle clay - in the embankment.

Now, 150 years after the Great Sheffield Flood, what matters most is that those who lost their lives continue to be remembered.