Sheffield DocFest: How film festival helped city 'reinvent' itself

- Published

Major filmmakers attended the festival's first edition

Sheffield DocFest, the documentary film festival, launched nearly 30 years ago at a venue with no screens in a city struggling after the collapse of its steel industry. Three decades on, the event has grown into one of the biggest in the world.

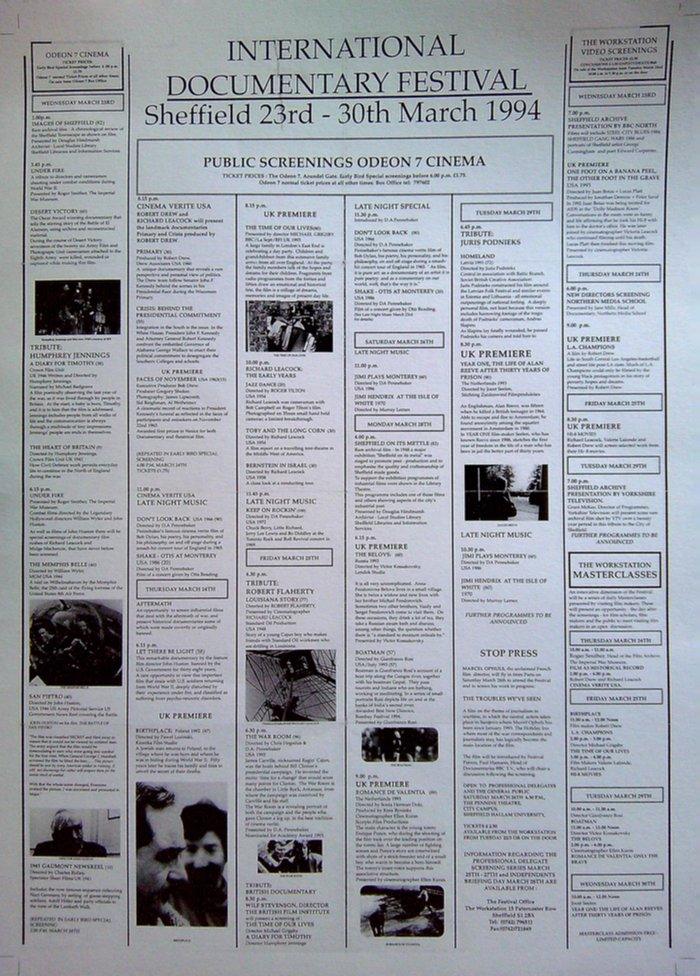

Mrs Doubtfire and Schindler's List were riding high at the box office as people settled into seats at Sheffield's Odeon 7 cinema on the afternoon of 23 March, 1994.

But the audience were there to watch a film that was markedly different from the latest blockbusters - and which would begin a highly significant chapter in the city's cultural history.

The screening of Images of Sheffield, a chronological compilation of footage of the city unearthed by local archivist Doug Hindmarsh, was the first at the inaugural Sheffield International Documentary Film Festival.

DocFest, as it later became known, is now in its 30th year and has grown to be one of the biggest events of its kind.

Its 2023 edition, which is taking place this week, sprawls across 22 venues including the City Hall and Crucible Theatre. More than 32,000 people are expected to attend a programme boasting 37 world premieres, as well as theatre, live podcast events, industry sessions and talks from actors such as David Harewood and Rose Ayling-Ellis.

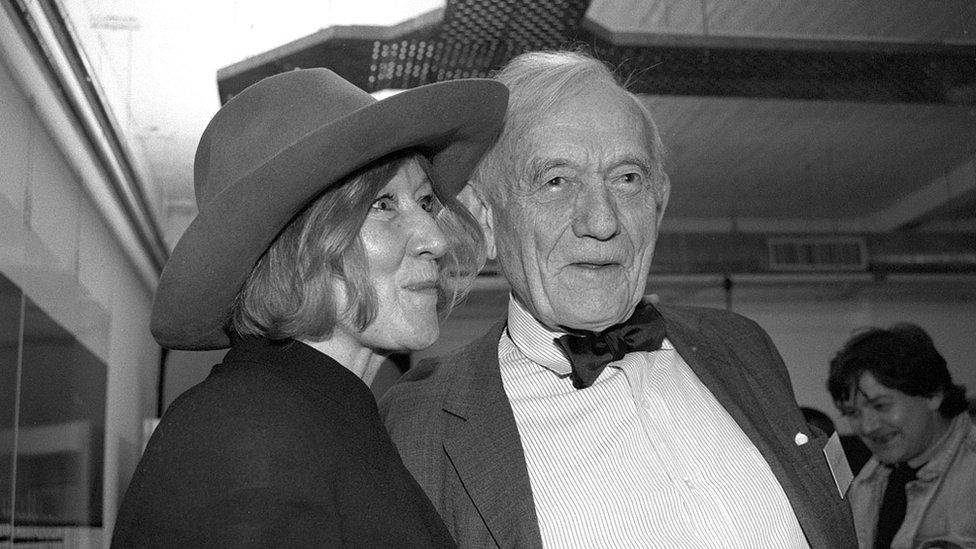

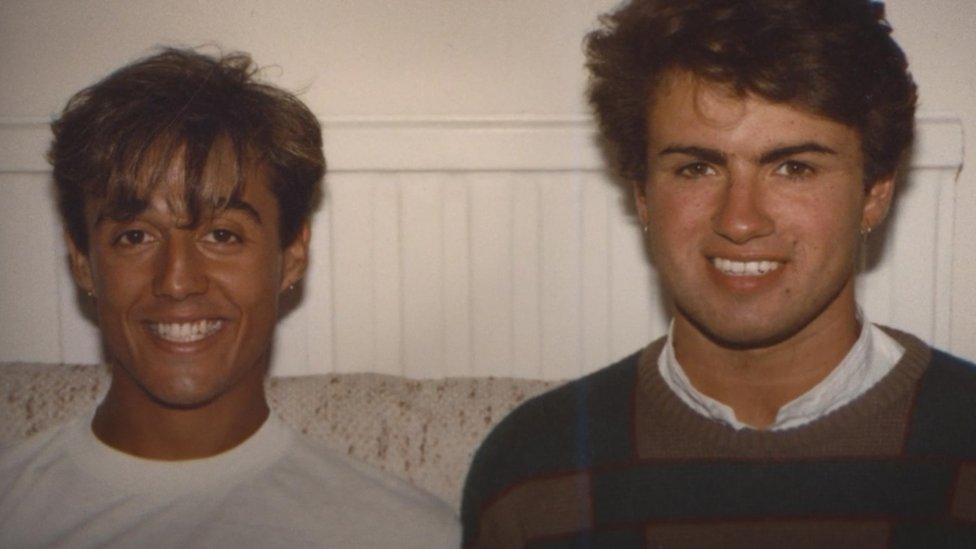

Midge MacKenzie, the festival's first director, and filmmaker Richard Leacock

The first festival, three decades ago, was rather more humble.

It had been hoped the event would take place at the newly developed Sheffield Media and Exhibition Centre (SMEC), which - now known as the Showroom cinema - remains at the heart of today's festival.

But the renovation of the art deco building, a former car showroom in the city centre, was not completed in time, leaving organisers without any screens to show films on. Forced to improvise, they borrowed other venues such as university lecture theatres and turned the SMEC's foyer into a makeshift screening room using bin bags to cover windows and block out the light.

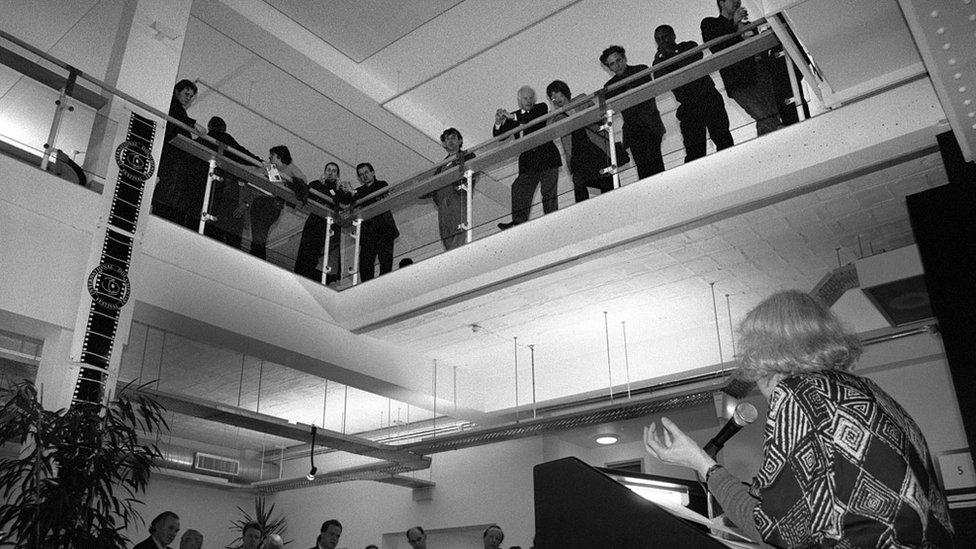

"We screened luminary documentary-makers' works in what basically was a glorified reception area with black bags on the wall and a video projector," said Colin Pons, SMEC's former chair and one of the organisers of the first festival, where he was also a projectionist.

"It really was bubblegum and blue tac. But we had the passion and that's all you need to make things work."

Films were shown in a makeshift cinema in a foyer of the Sheffield Media and Exhibition Centre

The festival's rough-and-ready setting did not stop it attracting major talent from the world of documentary cinema, with pioneering American filmmaker Richard Leacock and Oscar-winning French director Marcel Ophuls among those who attended to introduce their work.

There were also a number of archive-based screenings about South Yorkshire and its history, with titles such as Sheffield Gang Wars, Sheffield on its Mettle - which focused on the city's industry - and Steel City Blues, a short film about Sheffield Wednesday.

The festival's first programme included international films and local archive footage

For many in the film industry, Sheffield is now synonymous with DocFest - but the city was not originally envisaged as the host. The festival's national organising committee had originally planned to hold it in Bristol, before their failure to secure funding from local authorities forced them to look further afield.

Sheffield, lacking in cinemas and in decline following the collapse of its steel industry in the 1980s, did not seem an obvious choice for an international film festival.

But the city had a thriving independent film scene and Sheffield City Council, which envisaged culture as a key part of its urban regeneration plans, supported the event.

"It was just trying in a way to create good and satisfying employment in our part of the world which we saw as coming at that time from media," said Mr Pons. "I think in that sense the DocFest really does focus on the efforts of the good people of Sheffield."

The Sheffield Media and Exhibition Centre, now known as the Showroom cinema, formed a key part of the council's regeneration plans

The council saw hosting a festival as "a key means of overcoming Sheffield's image problem" as it searched for a new identity for the city, according to James Fenwick, a senior lecturer in media studies at Sheffield Hallam University whose research has formed the basis of an exhibition on DocFest's history.

Anna Richards, curator of the exhibition and a PhD student at the university, said DocFest "came at the right time" for the city "in that it helped reinvent the identity of Sheffield in some way".

The first festival attracted around 2,000 visitors and subsequent editions cemented its status as an important date in the industry calendar.

But it was not until the 2000s that DocFest exploded into an event with more mainstream popularity.

Dr Fenwick said this was partly down to new directors who "really kind of focused on expanding it to become this major media event" by showing more "blockbuster" films and music documentaries and "had the contacts to do that".

But he added this had "coalesced" with improvements in Sheffield's infrastructure, such as the building of more hotels, which made the expansion of the festival possible.

The festival is showing a number of music documentaries this year, including Wham!

Alex Cooke, chair of DocFest's board of trustees, said the festival's ability to "keep reinventing itself" had been key to its success.

"I think it's that thing of being adaptable and thinking about audiences and what our audience is interested in and then sort of programming around that," said Ms Cooke, who was also a film programmer for the festival in the 1990s.

DocFest now brings £1.4m in spending to Sheffield each year, according to the council. But its true value to the city may be harder to quantify.

"It has become such a huge event in the cultural calendar," said Dr Fenwick. "Without it there would be a big hole in the cultural landscape of Sheffield."

DocFest 2023 runs until 19 June. An exhibition on the event's history is open at the Sheffield Hallam University Pop-up Shop on Howard Street during the festival.

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.