Why are football clubs banning local newspapers from covering their teams?

- Published

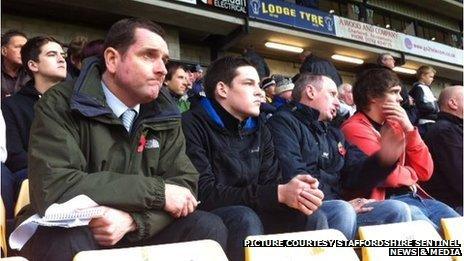

Michael Baggaley, of the Stoke Sentinel, is refused access to the ground

Another football club has banned a local newspaper from its press box for home matches. But what effect does such a move have on the media, the clubs and the fans who want to know what is going on at their favourite football club?

Every match day, Michael Baggaley packed up his laptop and took himself to the press seats at Port Vale Football Club to capture the cut and thrust of their latest League One fixture.

In doing so, Mr Baggaley was following a well-trodden trail of sports reporters who have covered the club for his paper, the Stoke Sentinel, for more than 100 years.

Down at pitch level, a Sentinel photographer was positioned behind the advertising hoardings, poised to capture any goalmouth action.

At least, that was how things worked until last Saturday. When Mr Baggaley and a photographer turned up at Vale Park they were told they were banned from the press box.

The newspaper said Port Vale chairman Norman Smurthwaite demanded a financial contribution from it of £10,000 to gain access to the club.

Port Vale is far from the first club to limit media access to its team.

On Tuesday, Newcastle-upon-Tyne's stable of regional papers - The Journal, The Chronicle and the Sunday Sun - revealed they had been banned from Newcastle United's press box following their coverage of a fans' protest march.

And Nottingham Forest has limited the city's daily newspaper The Nottingham Post's access to its management and playing staff to post-match press conferences.

So why are some clubs adopting such an uncompromising stance towards local newspaper coverage? And are such practices likely to become widespread?

What the papers say

Newspapers feel baffled at the clubs' actions.

"We have helped save the club - why would we want to damage it?" asked Stoke Sentinel editor Richard Bowyer, referring to his paper's campaign to expose financial irregularities at Port Vale.

Since the ban, sparked by a story the paper ran about fans not receiving replica shirts, Mr Bowyer's team faces having to report on the club from the stands.

Coverage of a fans' protest march at Newcastle United prompted the club to ban local newspapers from press facilities

He said the idea of charging the newspaper to cover matches was unprecedented.

"There is not one local newspaper in the country I know of that pays any money to sit in a press box," he said.

"If I added up how much coverage Port Vale get in terms of advertising space, it would be thousands of pounds a year. But we are pleased to do this."

In addition, journalists say the coverage they provide is unparalleled, honest, knowledgeable and objective.

"Newcastle is a football-mad city and it is our duty to report on the club," said Lee Ryder, chief sports writer at the Newcastle Chronicle.

"Unlike the players, journalists don't have to toe the party line and we don't come out with cliche-ridden quotes that fans have heard before.

"I've watched Newcastle United all my life, so I write from a position of authority and what I write is balanced."

What the clubs say

In the high-pressure, high-spending world of modern football, clubs feel they have a brand to protect.

"Times are changing," Ben White, media and communications manager at Nottingham Forest, said. "We have a media team of our own who are fully focused on keeping fans updated.

"We haven't banned any of the local media. They still have access to the press box and can attend post-match press conferences with the manager."

Since January, however, Forest has ceased to allow journalists from the city's newspaper and radio station daily interaction with its management and players.

It is a far cry from the club's halcyon days under Brian Clough in the 1970s and 80s, when not only were Forest European champions but local journalists such as Duncan Hamilton, who wrote an award-winning book, external based on his years of dealings with Clough as a reporter for the Nottingham Evening Post, were virtually permanent guests in the manager's office.

All breaking news about the Championship club is now released via the club's website and social media channels.

"We fulfil all the contractual rights of the Football League," said Mr White.

He makes no distinction between independent press coverage and that provided by the Forest media team.

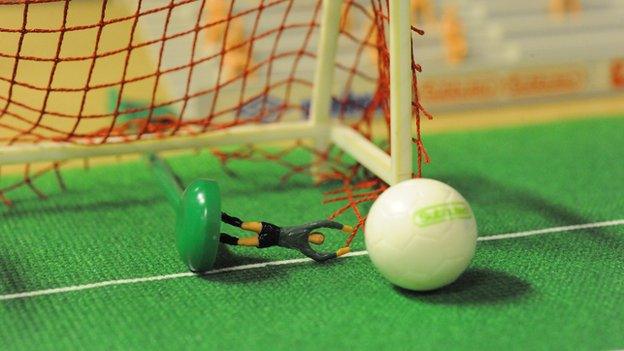

The Swindon Advertiser used Subbuteo figures to recreate a 2010 match against Southampton

Southampton decided to ban press photographers from its ground - other papers used old photos or employed a cartoonist

Southampton has now changed its policy but other clubs have restricted media access

Media experts describe the trend as "worrying"

"There are so many rumours floating around in football and we want people to come to our website and get the facts," said Mr White.

However, some facts are, inevitably, more palatable to a club than others.

The press restrictions at Port Vale and Newcastle United have been imposed in response to stories they considered damaging.

Port Vale chairman Mr Smurthwaite said his concerns related to a number of Sentinel stories, including one about former chairman Paul Wildes - although the Sentinel said it had never received a complaint about that article.

Newcastle United refused to comment on its falling out with the three Newcastle papers but in a letter to their editors Wendy Taylor, the club's head of media, described recent coverage of a fans' protest march as "completely disproportionate".

None of the three clubs commented on when they were likely to lift the restrictions. Mr Smurthwaite said he hoped the Sentinel would issue an apology to him, while Nottingham Forest said they would review their strategy at the start of each season.

What the fans say

While the clubs' restrictions may be problematic for editors and galling for defenders of press freedom, the question remains whether they matter as much to followers of the teams concerned.

Fans of clubs in the upper reaches of the Premier League have probably never been exposed to as much news about their teams as they are in the modern world of 24-hour media, internet message boards and social networking.

But supporters of lower-division clubs, who inevitably receive less national coverage than their more successful counterparts, are more likely to find themselves relying on local media for news.

Kevin Miles, a former freelance journalist who now heads the Football Supporters Federation, said: "Realistically, the ban at Newcastle on one set of publications is not likely to majorly impact what a fan can find out about their club.

The Sentinel bought its reporter a ticket to watch the match from among the fans

"But the smaller the club, the narrower the range of outlets covering it, so the bigger the impact of any media ban."

In response to the idea that clubs' websites could become the main outlet of coverage, he said: "Among fans, there is a genuine suspicion of clubs' websites. They are seen very much as a propaganda outlet."

Peter Williams, honorary president of the Port Vale Supporters' Club, said: "The Sentinel has stuck their neck out a number of times in support of the fans, during many of the problems we have experienced at Port Vale. They have worked tirelessly to help us.

"There are a considerable number of people who depend upon their reports, like my mother-in-law, who's 93 and can't go to the matches any more."

What happens next?

In the meantime, the affected newspapers are finding inventive ways of continuing their coverage, through a mixture of social media appeals for fan photographs, interviews with ex-players and match reports written from the stands.

They can draw inspiration from papers such as the Swindon Advertiser, which in 2010 used pictures of Subbuteo figures to depict the action when its photographer was denied access by Southampton, who wanted media outlets to buy its own official photos.

The Plymouth Herald got round the same ban by hiring a cartoonist, external while the Bournemouth Echo used photos from matches between Southampton and Bournemouth in the 1980s.

Mr Miles believes clubs may be forced to reconsider the bans - if only as a result of the poor PR they have received.

He says he cannot see such actions becoming widespread.

That said, he acknowledges that local papers - many of which are already suffering from falling sales - could be hit hard by such actions.

Tim Luckhurst, who heads the University of Kent's centre of journalism, described the bans as "a very worrying phenomenon".

"There is a sense at the top of the Premier League that the management can control the message," he said.

"I'm afraid my impression of football is that clubs are very reluctant to even begin to understand the idea of free speech. They are not interested in being held to account in any way."

- Published19 October 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 March 2012

- Attribution

- Published25 August 2011

- Published11 August 2010

- Published10 August 2010

- Published9 August 2010