Staffordshire Hoard reveals its secrets

- Published

Conservator Kayleigh Fuller is one of a team responsible for reassembling items from the almost 4,000 fragments

Six years after the largest treasure haul of its kind was discovered in a field, experts continue to uncover its mysteries. But what has the Staffordshire Hoard taught us about the Anglo-Saxons, and what secrets might it still hold?

The items - out of almost 4,000 uncovered - reveal the work of highly skilled and technically advanced smiths.

They were even capable of chemically removing alloys in gold to make it seem more golden, and producing slithers of fine, embossed foil, today too delicate to handle directly.

All the items are believed to have been made in workshops in what is now England, with only the garnets imported - possibly from Sri Lanka or India.

Some of the plates are believed to belong to a helmet

Some of the foil decoration is too delicate to handle, so conservators use computer software or sometimes even pieces of printed paper to find out how they might go together

"At that moment in the 7th Century, they were able to create the best of all of Europe. We truly didn't give them enough credit," conservation coordinator Pieta Greaves said.

"Giving them that 'dark age' term is quite unfair."

As items are painstakingly reconstructed, the best of them are being added to those already on show to the public in Stoke-on-Trent and Birmingham.

The hoard

The Staffordshire hoard is made up of almost 4,000 fragments, belonging to an estimated 450-500 objects

It is thought to have been buried between 650 and 700 AD

Valued at £3.3m, it was discovered by metal detectorist Terry Herbert in July 2009, in a field in Burntwood, Staffordshire, with other items found later

The area was once part of the Mercia kingdom, which by the 8th century had become the most powerful in the country

Dr Giovanna Fregni is analysing some of the smallest fragments to understand how they piece together

Yet, possibly one of the most exciting objects in the whole hoard is yet to be reconstructed, and currently being worked on in the basement Birmingham's Museum and Art Gallery.

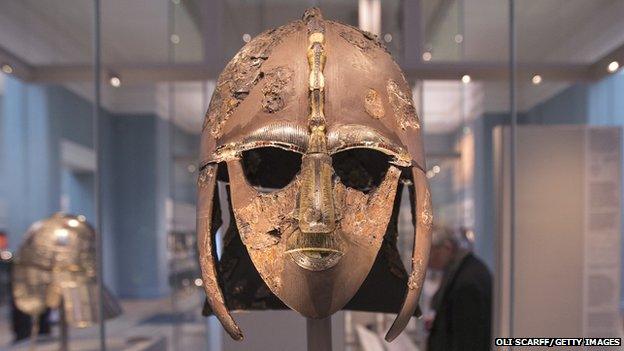

Conservators believe a set of decorated gilded silver panels, featuring armed warriors going to battle, belong to a helmet, not dissimilar to that found at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk (pictured below).

"If this is a helmet, and we're pretty certain it is, it would most likely be the helmet of a king.

"They're just so rare, this would only be the sixth known one," Ms Greaves said.

"The detail is such that you can even see a sense of movement, they're marching to war, fully armed," conservator Dr Giovanna Fregni said.

Conservators believe the full helmet would resemble the one found at Sutton Hoo

As well as piecing together the hoard, researchers will use the items to better understand the period

She is responsible for analysing the precious panels.

After all the pieces are assembled, the helmet will be digitally reproduced and the ultimate hope was that a reconstruction could then be made, Dr Fregni said.

One theory is that some of the items in the hoard could even have been produced in the same workshop as treasures found at the Sutton Hoo burial site, Ms Greaves said.

But that find pales into comparison to the sheer scale and value of the Staffordshire Hoard.

Researchers said many of the items, such as these seahorses or stylised horses, showed highly skilled work and were probably designed for kings or their elite warriors

"This is 60% more [Anglo-Saxon items] than everything we had in the country before," Ms Greaves said.

"There are 84 pommel caps from the top of swords, but before the hoard was found there were only 20 known ones in the whole of Britain."

The quality of items has also surprised researchers.

While some items are "more apprentice", the overwhelming majority were most likely made for kings and their elite warriors, the project team said.

The items, dating back to the 7th Century reveal a society on the cusp of change, researchers said, with paganism giving way to the new religion of Christianity

"We have almost 4,000 fragments, but we think it only represents 450 to 500 objects," Ms Greaves said.

The items, mainly gold and silver, sometimes decorated with garnets, were torn and hacked apart before being buried, making the conservation team's job even more difficult.

Archaeologist Chris Fern, and conservators Kayleigh Fuller and Dr Fregni are responsible for piecing together the various fragments.

Ms Fuller said some objects, made up of dozens of pieces, took several days to reconstruct.

Once items such as this filigree mount are conserved, the hoard will be handed over for further research

Similar styles, decorations, fixing holes, cut lines and corrosion marks all help the team to understand which pieces go together - a huge jigsaw puzzle.

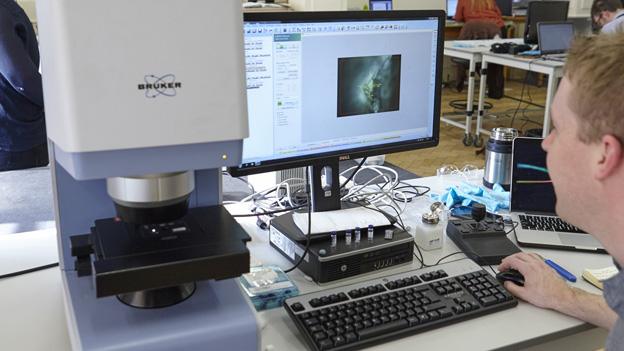

"Part of my job is to look at every piece, weigh it, measure it and become so familiar with it that I can identify it and understand exactly where it goes," Dr Fregni said.

"They're all measured in millimetres, but now I've been doing it for so long I can look at a piece under the microscope and understand straight away what it is."

Two of the most exciting finds, including a garnet encrusted sword pommel, were discovered as recently as May, almost six years after the hoard was recovered

Despite the challenge facing the conservation team, they hope to finish their job in the next year, before the hoard is handed over for further research.

When it was discovered, £900,000 was raised through a public appeal, alongside grant funding, to purchase it for the West Midlands.

Some items have been constructed from dozens of fragments, that were scattered among the 4,000 items

Further funds have been ploughed into its conservation, but £120,000 is still needed to complete the job and the project team hopes the public might come to the rescue once again.

"When the hoard was actually discovered they decided to put on a little display both in Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent. In Birmingham we had it for 19 days and 45,000 people came to see it," Ms Greaves said.

All items in the hoard are believed to have been made in Anglo Saxon workshops, although the red garnets, seen in this sword pommel, could originate from as far as Sri Lanka or India

"It was clear people were excited, even early on.

"It takes some dedication to queue for five hours to see a bit of gold glittering among some mud."

How and why the hoard came to be buried in a unremarkable field, near Burntwood, remains a mystery, however.

One of the main theories is that it was collected off battlefields and used as a treasury to be dispensed like modern day coinage.

The research effort has also seen the remains of organic matter, such as bone, hair and beeswax, analysed in a bid to understand how items were constructed

"It's not a single battle, there's just too much elite warrior gear in the hoard," Ms Greaves said.

"By the time you get them and all their men together, that should have been a battle we've heard of and it just doesn't exist.

"When you look at poems such as Beowulf, they often mention these elite warriors with their amazing weapons and fine decoration.

"But there was no archaeological proof of them, so it was thought they were made up.

"But actually, the hoard is that proof."

- Published26 May 2015

- Published4 August 2014

- Published12 March 2014

- Published17 October 2014

- Published18 December 2012

- Published18 December 2012

- Published29 October 2011

- Published3 July 2011