Minnie Pit: World War One mine disaster remembered

- Published

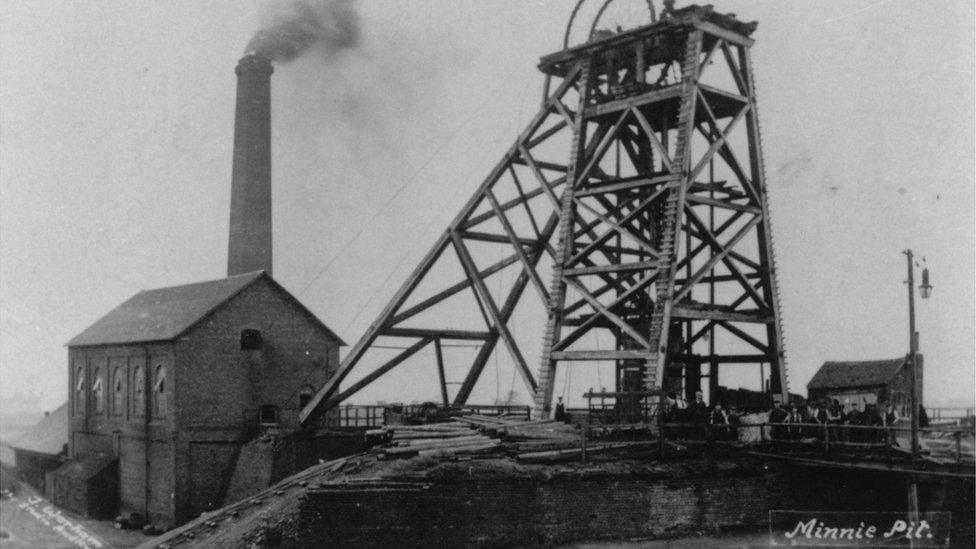

This picture of the Minnie Pit, supplied by the Audley Family History group, was taken by photographer Thomas Warham

Events marking 100 years since England's worst wartime mining disaster are due to take place.

The underground explosion at Minnie Pit in Staffordshire on 12 January 1918 killed more than 150 men and boys.

It devastated the village of Halmerend, near Audley, and is also said to have inspired Wilfred Owen's poem Miners.

Those still living in the vicinity of the pit are working to make sure the events and effects of that day are not forgotten.

Descendants of those who died were among the 400 people who took part in a memorial walk on Saturday.

Some were dressed as miners through the ages, with each of the 155 men and boys who perished represented.

What happened at Minnie Pit?

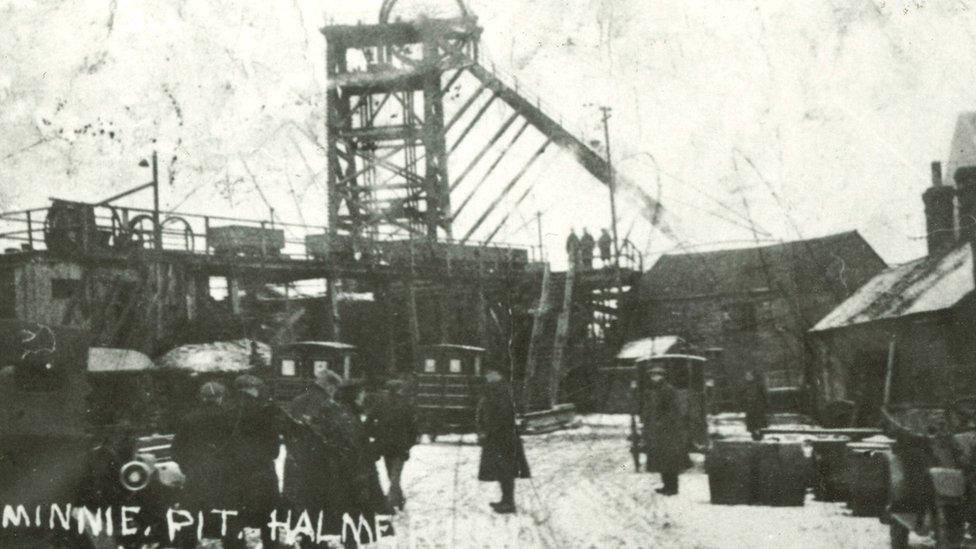

The scene outside the Minnie the day after the disaster

The explosion happened just before the morning "snap" time, when the miners were due a break

Many of those working in the mine were boys, or men who had been sent home from the trenches due to injury

Of the 155 who died, 44 were aged under 16

An inquiry into the disaster found it had been caused by a build up of methane gas in two of the pit's main seams

As a result of the gas in the mine, it was 18 months until the last body was recovered

Investigators concluded a faulty safety lamp had almost certainly caused the explosion

Survivors' stories

This mining rescue team is about to descend into the tunnels of the Minnie Pit following the explosion.

A number of those who survived or witnessed the blast spoke to BBC Radio Stoke in the 1970s.

Tom Burgess was 17 at the time, and described looking forward to "snapping time" with his 14-year-old friend Ernie.

"Just at that moment , there came a swoosh and the air came the opposite way.

"Instead of going in, it came with a rush.

"I went up the shaft and, on the top, oooohh, there were crowds of people and I can remember a girl, her name was Nancy Tipper, she'd be about 16. She asked me where her father was."

Wilson Taylor was 18 when the pit exploded, killing his brother.

"My brother, he was working close to me, in the stables. Well, if he'd have stopped where he was, he'd have been safe. But he knew I was round the corner and he put his vest in his mouth and run out, I suppose to get to me.

"Well, afterwards, I was talking to a fella. It was nine months after, they were still getting the bodies out. They were bringing a coffin along the pit bank and he says to me, 'you were a lucky chap weren't you?'

"I said I was the unluckiest man there was. He stared at me. Why he said, what do you mean?

"In an explosion, it isn't them that are in that suffer, it's those that are out."

'The guts was ripped out of it'

Christine Lamb's father lost two uncles and had a third injured in the explosion

Christine Lamb published her book about the Minnie, as the pit was known, in 2004.

"More died in the Minnie, in the village at that time, than in the war," she said.

Her father, who lost two uncles and had a third injured in the explosion, told her about it as a child.

"People went down into the pit and it was chaos. The guts was ripped out of it, as they would have said at the time.

"There were bodies, they found some very badly damaged bodies, some very damaged road works.

"Parts of the pit were just completely destroyed and there was chaos in some areas but quiet in others.

"I've imagined that atmosphere, the aftermath, many times when researching the book, writing the book and it still gives me a cold feeling what it must have been like.

"It must have been horrendous. There were quite a lot of bodies. Some people would have walked out, imagine the relief when your loved one is walking towards you.

"But then the next person could be your brother on a stretcher."

One hundred years later

A memorial to the Minnie Pit miners - villagers are determined to keep the memory of the pit alive

As well as the memorial walk, several other events took place over the weekend.

Villagers have worked with the Wilfred Owen Association to create a play being performed around the area.

One actor played Wilfred Owen and another played Nancy, the girl who went around the village asking if anyone had seen her dad.

A book, based on research by the Audley and District Family History Association, has also been published to mark the centenary.

Members gathered as much information on the victims as they could.

Clive Millington, whose great uncle died in the explosion, said they had very little information to start with.

"We went through records, traced family histories - it took two years of research and then longer to fill in the gaps. We didn't finish until the end of last year.

"Tracing some of them proved difficult."

Susan Moffatt, who has helped organise the play, said she wanted to use the centenary as an opportunity to bring the community together.

"Many people say the local kids don't know their heritage and many wouldn't know what coal is," said Ms Moffatt, who raised her children in Halmerend after moving there more than 30 years ago.

A memorial garden has also been created - 156 roses, one for each person killed, has been planted and an effigy of a coal miner pushing a pit tub has been created out of stainless steel to be put on a black background. The names of all those killed has been inscribed on the tub.

The village has been awarded World War One Heritage Lottery Funding so more research can be carried out, oral history recordings can be made and an exhibition and education packs prepared.

Mining during World War One

Samuel Healey (left) and James Platt served in the North Staffordshire Regiment before being discharged and both worked in the Minnie

Coal was crucial in the country's efforts during World War One, with miners working to meet an insatiable demand

It was needed to fuel ships, power stations and coke ovens, for home use and for the munitions industry

Many of those who ended up employed in the pits were too old to enlist in the Army, or young boys

As the conflict dragged on, more men left the mines to fight, and some mines were closed due to a shortage of workers

In some instances, men were sent back from the forces and honourably discharged to train others as miners.

Hundreds of miners died below ground in the early years of the 20th century, with causes ranging from explosions to roof collapses

The dead remembered

More than 400 people turned out to remember the victims of the Minnie Pit disaster, with names of the dead read out after a memorial walk

Hundreds of people visited Halmerend to mark the centenary of the disaster, with more than 400 taking part in the walk.

Many of them were descendants of those killed at Minnie Pit.

Andrew Pointon had six members of his family killed in the blast, including Ralph Pointon, his great-uncle, who was 16 when he died.

He said: "For my grandfather it was a real taboo subject, he never really liked talking about it.

"Probably going to his grave, he had never actually got over the death of his older brother."

He said he was pleased to see so many people remembering what happened, adding: "I've never actually seen that many people in Halmerend, in one place at one time.

"I think it has been a fitting tribute to the village, what has happened today."

Andrew Pointon's great-uncle was killed in Minnie Pit. along with five other members of his family

Source: Bob Bradley, mining historian and former surveyor for British Coal