We are Stoke-on-Trent: 'Debt was a circle I could not get out of'

- Published

It is estimated people in Stoke-on-Trent owe £80m to high-cost lenders

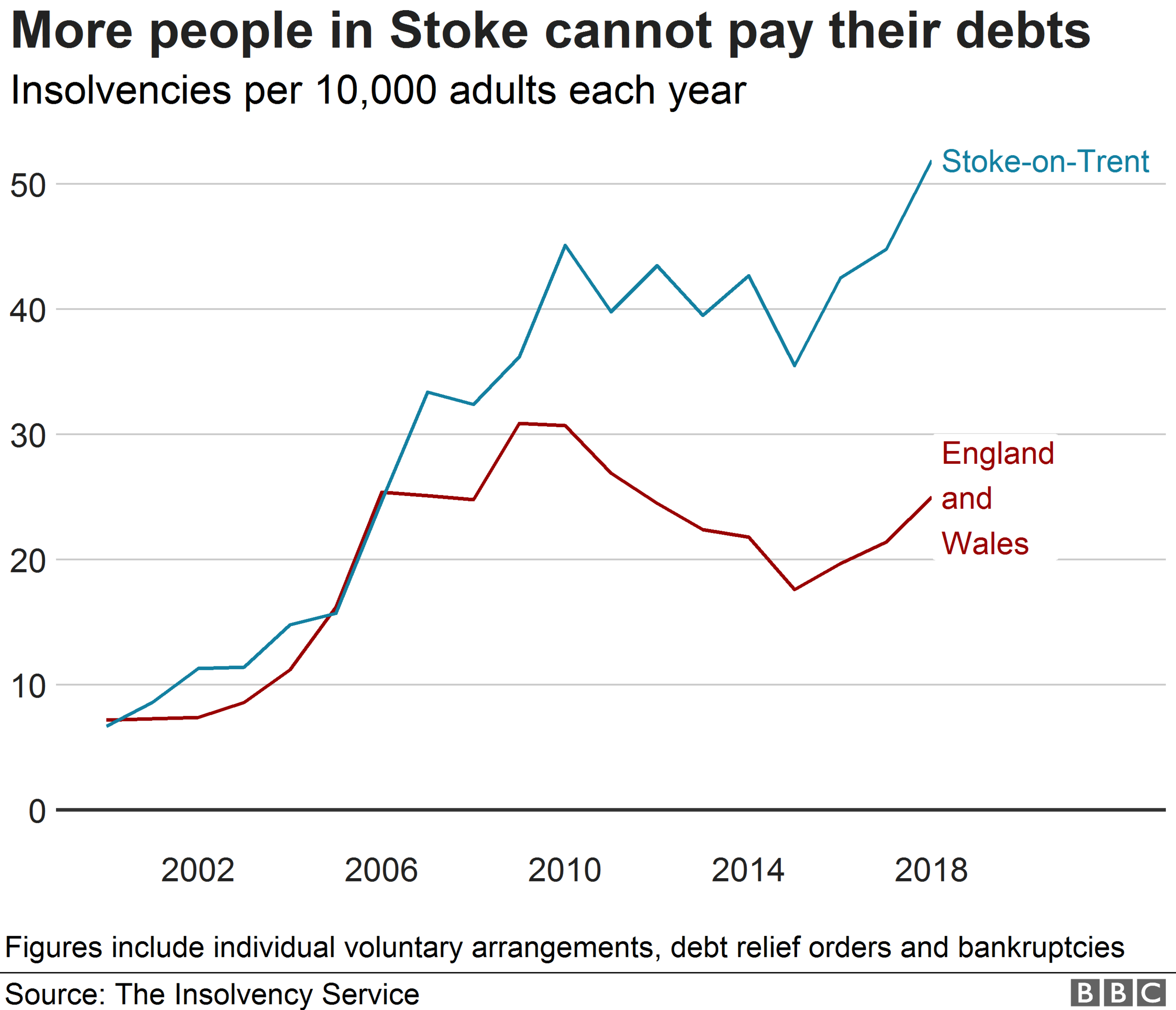

One in every 200 adults in Stoke-on-Trent became insolvent in 2018 - the highest rate in England and Wales. The BBC spoke to some who are managing to claw their way out of debt, and to those helping to fight the epidemic.

The haunted face of a new client arriving at the door has become a familiar sight to Anne Riddle.

"They're very frightened, and usually carrying a big bag - very occasionally carrying a suitcase - of unopened letters. Letters that they recognise the shape and colour or the print on so they haven't opened them. Because that's very often what happens - burying their heads."

The independent money adviser has seen her client list rise across Stoke in the past 10 years, as more people across the city are stifled by debts. She's also lost a few: those who could see only one way out.

"Suicide is as bad as it gets, when people can't face living because it just gets too much."

For two years running, Stoke-on-Trent had the largest proportion of people becoming insolvent - being unable to pay their debts - anywhere in England and Wales.

Debt adviser Anne Riddle says talking about debt with loved ones is an important first step

In 2018, almost 52 in every 10,000 adults in the city - a total of 1,029 people - had either an individual voluntary arrangement, a debt relief order (DRO) or went bankrupt. Scarborough had the next highest rate of insolvency with just under 48 in every 10,000 adults, followed by Torbay in Devon at just under 46 in every 10,000 adults.

Clare, a care assistant on a basic wage, became insolvent and took out loan after loan to make ends meet. By the time she went to see Anne Riddle, she didn't even know how many thousands of pounds in debt she had mounted up. She lives near Bentilee, in the most deprived ward of Stoke-on-Trent, where 45% of households have an income of under £15,000. Her problems began with a loan when she was a single mum in her early 20s.

"They say you can borrow £50, and then if you pay that back you can borrow £100. It keeps going up. And I thought I could do it, but then I realised I couldn't."

Panicking as the interest she owed rose, Clare took out more loans to try to pay off her escalating debts.

"When you've got a little 'un who comes home from school saying 'we're going on this trip, can I go?', you do what you have to do. It was very easy to get more credit. And I just used to ignore how bad it was getting. I couldn't sleep with worry, it made me ill. And then I had to take time off work - it was a circle I could not get out of."

The city has the highest rate in England and Wales

1,029People became insolvent in 2018

52in every 10,000 adults

27%above average for England and Wales

223were women aged 25-34, the group with the most insolvencies

A candid report into Stoke's debt situation by the Financial Inclusion Group (FIG) estimates about 100,000 people in the area owe a total of £80m to high-cost, short-term credit lenders. It identified low wages, poverty, poor health, and low levels of literacy, numeracy and IT skills as reinforcing "financial exclusion, trapping far too many people in a spiral of debt and deprivation".

"The debt and general personal financial position of many people in Stoke is extremely fragile," says Alan Turley, a former Stoke city council boss and FIG member.

"Many people are living on the very edge of financial catastrophe."

What do to if you're struggling with debt

Tell someone you trust - be open and honest with your loved ones. They might be able to help you deal with letters you've been receiving, and help you put together a budget

Prioritise - work out which of your debts should be paid off first, i.e. the ones with the most serious consequences. Mortgage and rent payments are seen as the highest priority as non-payment can result in repossession or eviction

Get professional help - if you can't pay your debts there are many free advisers who will help you find the best way forward. Citizens Advice, external has specialist money advisers, and other organisations that can help include StepChange, external, Business Debtline, external, Christians Against Poverty, external, Debt Advice Foundation, external, National Debtline, external and Shelter, external

There are many reasons why Stoke in particular has suffered financially. For decades, it was powered by industry, with tens of thousands working in mining and pottery. But when the mines and factories closed, generations of people were left out of work, creating a culture of not working that has trickled down to "third, fourth generations of people", says Ms Riddle.

In place of the lost industry, minimum wage-paying distribution centres are emerging as the big employers. The average full-time salary for workers in the city is £24,907, almost £5,000 less than the national average. Many people simply don't earn enough to keep themselves afloat, according to Julie Prendergast of the city's Citizen's Advice Bureau, which sees people every day with money worries.

"It used to be all credit cards and unsecured loans, but now we see more and more people who haven't got enough money for the priorities - so it's mortgage arrears, council tax arrears," she says.

"Changes to the benefits system haven't helped. Even if someone has a job, they can't always manage the basics."

More from the We are Stoke-on-Trent project:

'The buses are so bad, going out is pointless'

How ceramics are powering your car and phone

Cafes where the lonely find friendship

Joe knows that feeling. The 22-year-old warehouse operative was tempted by a type of lender that has replaced many payday loan companies - one that had teamed up with his employer.

"It was so easy," he says. "I applied through a place where I was working for a loan that would be taken out through my wages and by the end of the week I had £3,000 in my bank."

Joe got his car fixed and took his first holiday. But he then began to borrow more until his debts grew to about £8,500.

"That's where my problems came in really because when I found myself struggling to pay them back that's when they really increased. I wasn't letting my family know that I was in debt; I was really on my own with it because I was embarrassed. Every morning I'd wake up worried I would get found out."

One in every 200 adults in Stoke-on-Trent became insolvent in 2018

Clare's family only realised the extent of her problems after she suffered a stroke brought on by ill health at the age of 45 - it was at this point they started opening the many threatening letters that came through her letterbox.

"They said 'you've got to do something about this' and that's how I met Anne," she said. "I don't know how I would have coped without her. Many of my friends are in the same situation and I've just told them they need to get help.

"I am so relieved now - I can sleep, and I'm a calmer person. It was a terrible time and I wish it hadn't got so bad."

Joe and Clare both eventually sought help and are both clients of Ms Riddle's. They now have debt relief orders, which could eventually see what they owe written off, although this will affect their credit rating.

It is five years since the Financial Conduct Authority introduced stricter affordability checks for payday loan customers.

It also set a price cap that slashed the typical interest rate, and said nobody should ever have to repay more than twice the amount borrowed. The result was an immediate contraction in the industry which saw numerous outfits collapse, including one of the most well-known, Wonga.

But this created a gap in the market for more sinister lenders, says Ms Riddle.

"By closing a lot of those down, we've got loan sharks back in business again who are very heavy-handed, who work on the black market, who aren't regulated and it's a very dangerous situation for people."

In Stoke, the age group with the highest rise of personal insolvency in 2018 was 25-34, and 58% of those declaring insolvency were women. Many fit a "low wages, low literacy" profile, while others are of a generation that is impatient and overspends, says Ms Riddle.

"I think people have got more flippant about borrowing money. I think there's a more serious problem today.

"So many people seem to have got a culture of borrowing without responsibility. Younger people want it now, they'd rather pay for it and have it now than save for it and get it later."

The Rev Malcolm Mycock fell into this trap. In 2007, when he was 36, he left a career working with animals to run his own company providing equipment to zoos. His attitude to money at the time cost him his business and he almost lost everything.

'It's fatal - people lose lives through debt'

"The business grew and developed quickly and was fairly successful [but] very quickly I realised even money didn't make me happy.

"I started to spend more and more to find happiness. I was living a life beyond my means - not paying tax on time, not paying VAT on time, generally overspending in the household, too many holidays.

"I believe it could have been very successful if it wasn't for me."

After two years Mr Mycock had no choice but to go into liquidation and he was declared bankrupt. He says there is a misconception that it is an easy way of wiping debt clear.

"This is not the case. Often the debt will still follow you or be passed on to your spouse, my wife in this case. We still had to pay the money back."

'Bold, innovative' action

In the end, it was attending Alcoholics Anonymous that helped Mr Mycock. "I remember feeling very scared, guilty, ashamed, broken," he says. "The drinking got worse and my mental health suffered. I could not see any way out, life seemed pointless at that time."

After getting his life back on track he embarked on a new career in the church. He is now the vicar of Bentilee, where many in the community are living in debt.

To combat the wider issue of indebtedness across the city, FIG has a five-year plan. The group, alongside 14 partners, says the scale of the problem is so large, any significant impact is "through a response that is bold, innovative and above all on an unprecedented scale".

Its business development plan includes working with schools to ensure financial matters are an integral part of the curriculum, ensuring children leave education with a sound knowledge of banking and the risks of taking out credit. FIG also plans to target those who might be struggling by going out into the community - rather than assume they might one day seek out help - by having a presence at gyms, or the school gates, for example.

"We want to work on all the things that contribute to the problem, from better education for the next generations to up-skilling adults that missed out on that, from helping people start saving to getting them out of the trauma of facing the bailiff," says Mr Turley.

Mr Turley points out that some people manage to live within their means - however limited those may be.

"We must recognise that many people in Stoke have managed to cope with very low household income over many years and never been in debt that they couldn't manage - amazing people."

Bentilee is among several areas of Stoke-on-Trent where low-income families are at risk of falling into debt

But until the dangers of taking out credit are made transparent at the point of sale, those who are naive to the risks - or desperate enough to ignore them - will always be vulnerable, according to Mr Mycock.

"There's still adverts on the telly and the radio that say 'we don't care about your credit rating, you can buy a car from us', or 'we'll give you a loan, you can have a credit card at 50% APR'," he says.

"People are still being taken advantage of. I think people think 'well that's normal'. We're in a society where if you want something, you think you should have it now.

"I think I was there - this is just how we live today."

Why Stoke is the insolvency capital on England and Wales: Money Box - Struggling with insolvency - BBC Sounds

If you need advice over managing debt, see the BBC Action Line page where there are details of several organisations that can help.

This article was created as part of We are Stoke-on-Trent, a BBC project with the city's people to tell the stories that matter to them.

- Published27 September 2019

- Published26 September 2019

- Published25 September 2019

- Published19 June 2019