More appropriate adults needed to safeguard rights of detainees - charity

- Published

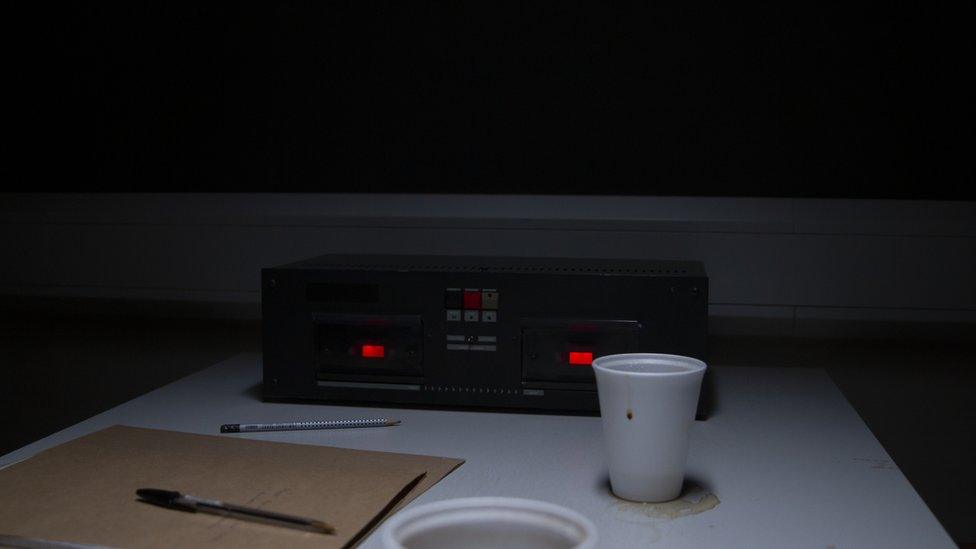

The work of appropriate adults like Fred Cox is invaluable, the Staffordshire police commissioner's office said

Thousands of people a year voluntarily turn up to police custody. They are not detainees, but rather volunteers there to support and protect children and vulnerable adults held on suspicion of crimes.

With demand for the role rising, volunteers share their stories.

Retiree Fred Cox from Stoke-on-Trent started volunteering as an appropriate adult, external (AA) after his wife died during lockdown.

"I was married for nearly 60 years and suddenly you find yourself on your own," he said. "It keeps me active."

"People get themselves in such a mess sometimes. They're not necessarily all bad people, they've just done a wrong, silly thing and find themselves locked up."

He helps with a scheme organised by the Staffordshire Commissioner for Police, Fire and Rescue and Crime, external, which, like others across the UK, ensures children and vulnerable adults detained or questioned by police are treated fairly.

Mr Cox, a 79-year-old with a background in courts and probation, said he could be called up to six times a week.

He said suspects he had supported had been arrested on suspicion of a range of crimes, some of them the most serious - including the murder of children.

Despite the challenges, he finds working as an AA rewarding, citing a case of an autistic 18-year-old man he convinced to consult a solicitor.

"Quite a few of them, they appreciate you being there and they're very grateful for it - but you do get the odd few who resent it," he said.

On the rare occasions he has experienced issues with the actions of a suspect in custody - often linked to extreme mental disturbance - "you get out of the room pretty quick".

In the case of children, an Appropriate Adult could be a parent, guardian, social worker, or a volunteer as long as they are not connected to the police

The National Appropriate Adult Network (NAAN) says demand for AAs is increasing, although it believes there are many cases involving vulnerable adults that slip through the net.

Detainees can include people with learning disabilities, mental ill-health and neurodiverse conditions.

"AAs are a critical protection to ensure people are treated fairly by police. But the gap in identifying vulnerable suspects remains massive," said the charity's chief executive Chris Bath.

Following a freedom of information (FOI) request to forces across England and Wales, external, the NAAN found police had recorded the need for an AA in 7.3% of adult detentions in 2021, up from 5.9% in 2019.

But the charity believes a more realistic figure could be as high as 39%, external, which would mean as many as 200,000 detainees a year not receiving essential support.

The FOI data also reveals stark differences between forces.

While Derbyshire Police recorded the need for an AA to be present in 18% of cases over the three-year period, Staffordshire Police noted it in 4.2%, Warwickshire 1.5% and Dyfed-Powys Police in just 0.3% of total detentions.

The NAAN points out in some cases that police may have failed to secure an AA.

Your device may not support this visualisation

While local authorities are legally obliged to provide one for children, there is no statutory duty on any organisation to do the same for adults.

"Police officers need training, tools, and access to local appropriate adult schemes that are on a statutory footing," Mr Bath said.

"But the best thing we could do is reduce demand. The scale of vulnerability amongst suspects raises questions about whether we are asking police to pick up the pieces from failures elsewhere."

The National Police Chiefs' Council said it was working to improve identification of vulnerable adults in custody, highlighting a national training package developed following Dame Elish Angiolini's review into death and serious incidents within police custody.

It is the responsibility of custody sergeants to identify the need for and secure an independent AA

Ella Worrell, 37, who volunteers as an AA for Southwark Youth Offending Service, external, has witnessed the confusion experienced by people with mental health conditions when they are detained.

"The most rewarding thing is when someone just turns to you and says 'thank you, I really couldn't have done that without you'," she says.

Ms Worrell, a trainee solicitor who hopes to become a barrister, wanted to see the justice system from all angles and help the most vulnerable.

"People aren't always from backgrounds where they've been fortunate to grow up or live in a certain way, and I can feel like that can really impact on why they've ended up in the police station," she said.

"I feel like for the little time I'm in that police station with that person, I'm literally trying my hardest to make a difference."

She believes her age also helps younger suspects open up, with one young person choosing her over their parent to be present during an interview.

"It made me think if I was there, and was in my 50s or 60s, would they have felt the same?" she said.

Lizzie Shenton started volunteering as an independent custody visitor 26 years ago

The legal requirement to provide an AA was established in the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (1984) Code of Practice, external.

In a statement, the Home Office said it was "vital all detained vulnerable adults are supported by an appropriate adult while in custody".

"Officers should carry out a vulnerability assessment, taking account of their appearance and behaviour, any signs of illness or injury, their style and level of communication, information from all sources and the circumstances in which they were found," a spokesperson said.

The monitors

While AAs participate in police custody proceedings, Independent Custody Visitors (ICVs) are more like independent monitors.

They make unannounced visits to facilities to check on the rights and wellbeing of detainees.

Former council leader Lizzie Shenton, from Newcastle-under-Lyme, started volunteering as an ICV when the scheme launched in her area 26 years ago.

She now co-ordinates the north Staffordshire panel and, paired with a buddy, drops in on individuals held in the region's 50-cell Etruria custody facility.

"It's a very privileged role," she said. "We're there as a snapshot of how they're being looked after whilst they're being detained."

ICVs observe the whole facility, including food preparation areas and the state of empty cells, before compiling reports for commissioners.

Mrs Shenton said some cases stayed with her, such as that of a young boy from a children's home arrested after being separated from his sisters.

"He... kicked off and kicked a door and police were called and he ended up in a cell, and it's very hard because of people's circumstances that have led them there," she said.

Antony Jones said sometimes detainees were unaware they could shower, or go for a walk in a yard

About 1,400 ICVs in the UK carry out more than 5,000 visits a year, according to the Independent Custody Visiting Association (ICVA), which describes them as an "incredible resource".

"ICVA regularly receives reports where independent custody visiting volunteers have made positive changes to custody and where issues in detainee care and wellbeing have been highlighted and remedied," chief executive officer Sherry Ralph said.

Antony Jones, 55, from near Lichfield, has been visiting adults and children held at a custody suite in Gailey, Stafford, for about 12 months.

The job is a "two-way street", he said, also making sure police officers are happy in their environment.

"I think the police appreciate us going in because we're like a second check. We can go in and find out something may have been missed," he said.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published28 September 2022

- Published26 August 2015

- Published30 October 2017