Holocaust Memorial Day: Survivor recalls 'hell on Earth'

- Published

Frank Bright with his father Hermann in Berlin; as a boy; on his 1945 visa application. and today at his home in Suffolk

Aged 16, Frank Bright was taken to Auschwitz. He avoided the gas chambers, but his mother and father did not. Now 88, he visits schools in the UK to talk to pupils, in the hope that future generations will learn from the mistakes of the past.

Mr Bright can still remember the "terrible" stench of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the concentration camp where he arrived on 12 October 1944.

"It was the stench of death," he says. "People had the power of life and death over you. It was hell on Earth."

Mr Bright was living in Prague when he was sent to Auschwitz with his mother a fortnight after his father. He made it out. They never did.

His parents were among an estimated 1.1 million people killed at the camp in Nazi-occupied Poland during World War Two.

He has never forgotten their fate, and is determined that no-one else does, either.

Frank Bright is now retired and living with his English wife near Ipswich

Now retired and living near Ipswich, Mr Bright still visits schools in the area to share his own terrible experiences with students.

Born Frank Brichta in Berlin in 1928, he was brought up as the only child of Hermann and Toni Brichta.

The Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, but it was not until 1938 that the Jewish family decided to leave.

"Things started to get pretty bad. I remember a newspaper vendor on the corner had cartoons on his stand which were anti-Semitic," Mr Bright says.

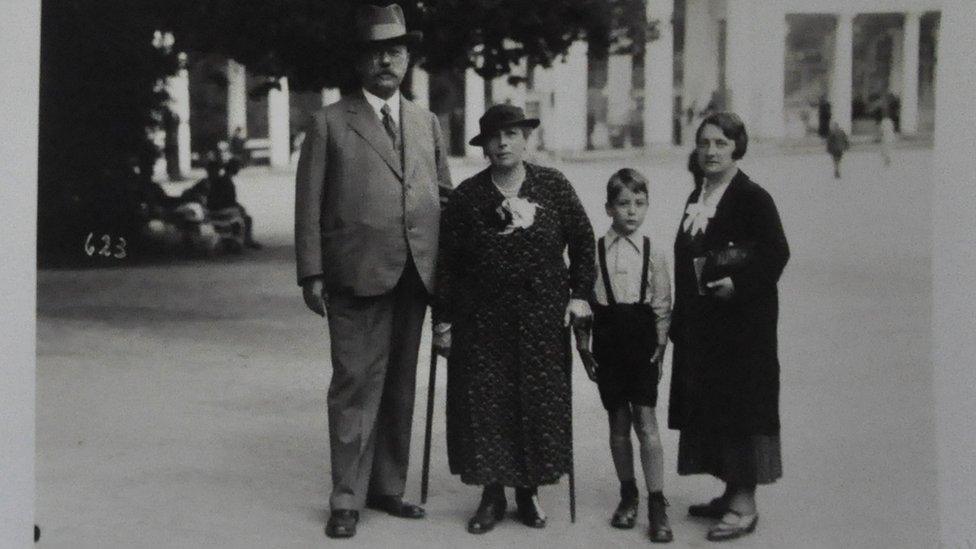

Frank Bright (second from right) last saw his mother Toni (furthest right) when they were separated on arrival at Auschwitz

"The Nazi newspapers showed Jews with big noses either dressed as Russian communists or American capitalists in top hats. Either way you couldn't win; you were a menace."

The family fled, but by Mr Bright's own admission, went "the wrong way". They headed east to Czechoslovakia because his father, who was born there, had a Czech passport, rather than attempting to emigrate to western Europe, the United States or Palestine.

They settled in Prague when Mr Bright was 10, but the Germans were not far behind, occupying Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

As Jews, the family faced restrictions on what they could do, although Mr Bright did attend a Jewish school until its closure in 1942. In July the following year, they were sent to the Jewish ghetto created in the military fort of Teresienstadt, north of Prague.

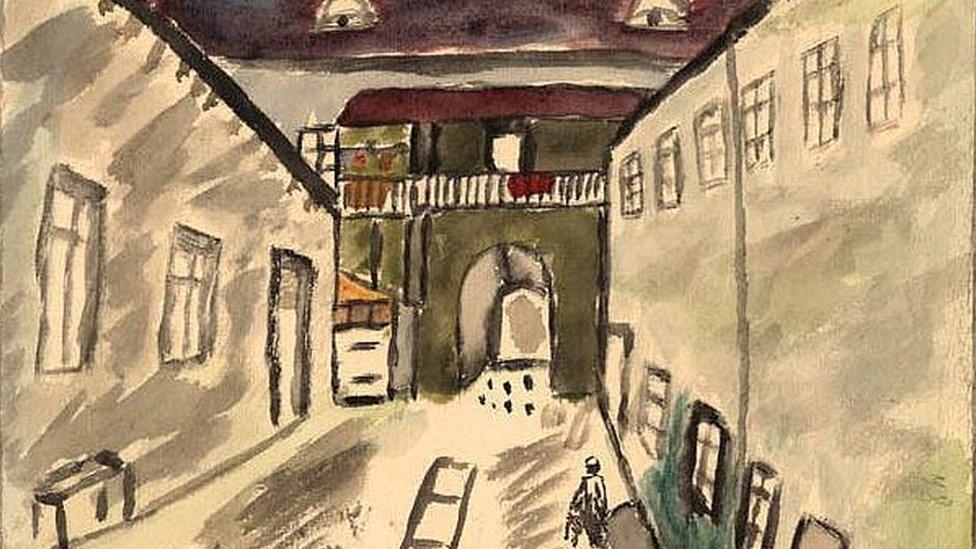

Frank Bright (circled) at a Jewish school in Prague during the occupation by Nazi Germany

By then aged 14, he was living in a separate part of the fort from his parents and working as a locksmith, although he was still allowed to meet up with them.

But in October 1944, his father was put on a train to Auschwitz as the mass evacuation of the ghetto's inmates to concentration camps began.

It was the last time Mr Bright saw him. A fortnight later, he and his mother made the same journey.

Upon arrival, mother and son were separated. Mr Bright was declared fit for work, but he believes his mother was sent straight to the gas chambers.

"My parents were murdered there: my father first and then my mother on the day she arrived there with me," he says.

Auschwitz - shoes from prisoners, canisters of the poisonous Zyklon B gas used to kill inmates and one of the gas chambers

"I was turned to the other side for people chosen to work: not to work properly, but to be worked to death.

"At the time I didn't know what was happening - we were confused, but I think my mother had an idea."

A few hours later, when he spoke to fellow prisoners, he learned what the chimney fumes and smoke signified.

"I remember wondering which came from my mother," he said.

"As a method of mental preservation, an emotional curtain comes down - it doesn't sink in.

"There were no tears at the time - you couldn't afford them if you wanted to survive.

"My grieving came later in life."

He left Auschwitz five days later to be put to work in a propeller factory in Friedland in modern-day Poland.

"The aim of the SS was to kill us, too. The fact that they wanted to make use of us wasn't out of the goodness of their hearts."

After seven months of slave labour, the 16-year-old was freed in May 1945 when Soviet troops pressed west and the Germans retreated.

German civilians were made to look at the corpses at Auschwitz at the end of World War Two

After making his way back to Prague into the care of the Red Cross, he eventually secured his passage to London where he was able to live with distant relatives, who he had only met once before.

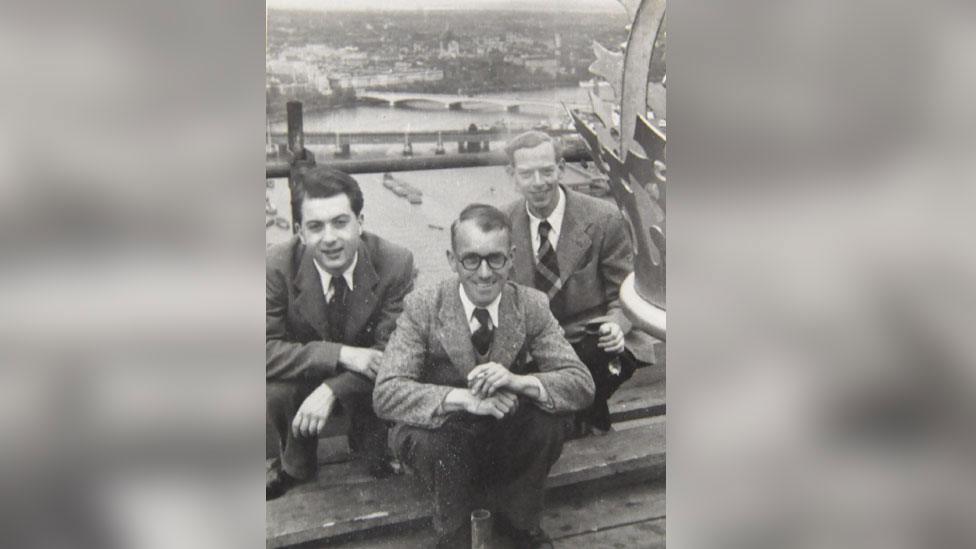

Frank Bright (left) pictured on the roof of the Palace of Westminster when he worked for the Ministry of Works after World War Two

Eventually he was able to build a life for himself as a civil engineer in Canada before returning to the UK to work with local authorities, including Suffolk County Council.

He married an English woman, Cynthia, and the couple have two daughters: Toni (named after his mother) and Miriam, who are both in their 50s.

But his traumatic childhood experiences left an indelible mark.

"My life was turned upside down, because it wasn't normal: you wouldn't normally spend your youth being marked as a Jew with a yellow star and you normally have an education, of which I was deprived," he says.

"You aren't normally split from your parents in a ghetto where they are themselves split from one another.

"You're not normally on your own after that in a slave labour camp.

"When liberated, you know full well you have no parents left; you're on your own with no education and life will be very difficult."

Mr Bright has no grandchildren, but for several years he has been sharing his experiences in schools. It "keeps me going," he says.

The Holocaust is a compulsory part of the school curriculum.

"It is extremely important that it is still taught, because it is the modern history of Europe and it can help you judge what Europe and Brexit is all about," Mr Bright says.

"I'm very depressed about the current state of the world, because obviously people haven't learnt and, as some philosopher said, if people don't learn from the past, they will repeat their mistakes."

Holocaust Memorial Day, external is on 27 January each year - marking the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

- Published21 January

- Published10 October 2016

- Published26 January 2015

- Published14 April 2014