The Dig: Who was Sutton Hoo archaeologist Basil Brown?

- Published

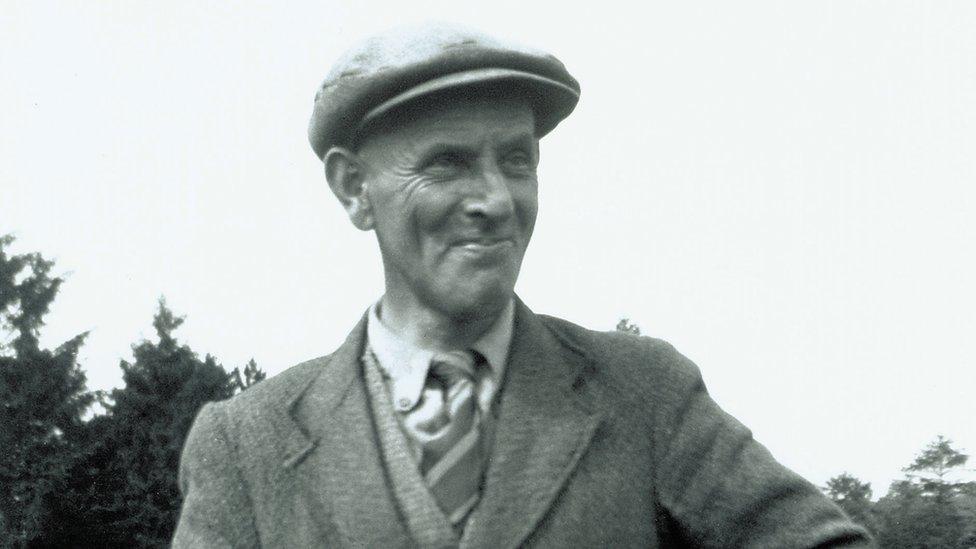

Basil Brown was an archaeologist who worked for Ipswich Museum

Archaeologist Basil Brown unearthed some of the greatest treasures ever found in the UK. The story of the Sutton Hoo discovery is being retold in the new Netflix film The Dig. Who was Mr Brown and what was his role in revealing the Anglo-Saxon finds?

Who was Basil Brown?

Born in 1888, he was the only child of farmer George and Charlotte Brown.

He spent almost his entire life in the Suffolk village of Rickinghall and left the local school there at the age of 12.

Despite his limited formal education, he taught himself several languages and studied diplomas in astronomy, geography and geology, says historian Caleb Howgego.

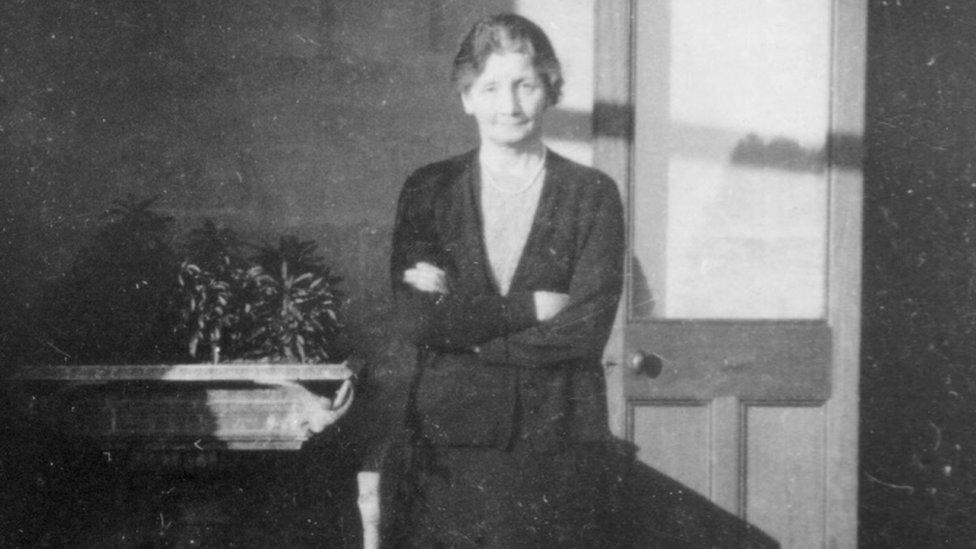

The relationship between landowner Edith Pretty (played by Carey Mulligan) and Basil Brown (Ralph Fiennes) forms the backbone of the film The Dig

He was rejected for front line service during World War One on medical grounds, but volunteered for the Royal Army Medical Corps.

On 27 June 1923, he married Dorothy May Oldfield, who was known as May.

The couple, who had no children, took responsibility for the family farm, but according to Suffolk Archives, external, Mr Brown was "more interested in studying the night sky or excavating the ground beneath his feet".

What was found at Sutton Hoo?

The remains of the Sutton Hoo warrior's helmet are at the British Museum in London, with the pieces mounted to show where they would have been on the complete helmet

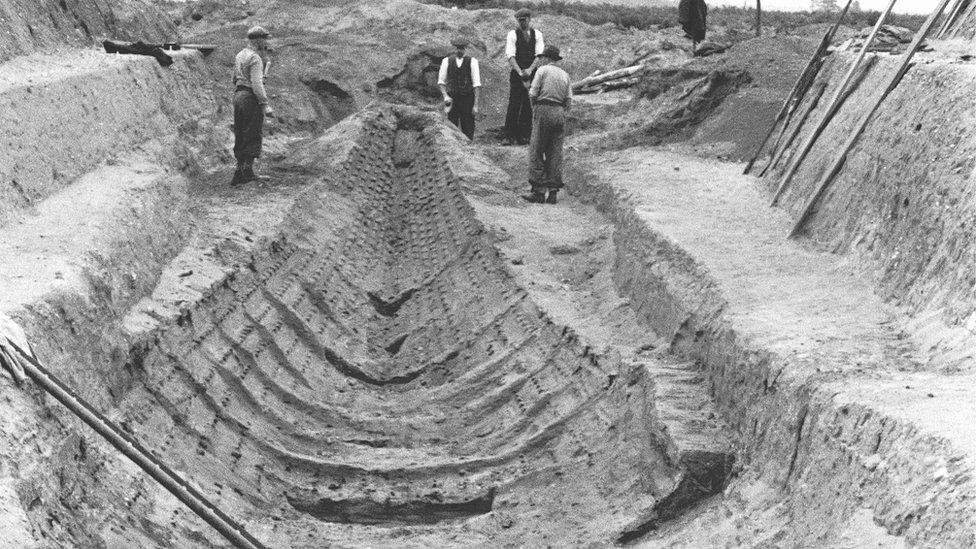

The 27-metre long (88ft) wooden burial ship had long since rotted, leaving only the iron bolts and the impression of the timbers in the earth

In the middle of the ship was a chamber containing the body and treasures for the "next world", including the remains of the iconic warrior's helmet, a sword, a complete gold belt buckle, Byzantine silverware and a feasting set

No written records exist from the Anglo-Saxon period in East Anglia, but the burial is widely believed to have been of King Raedwald, who died in AD624

The ship is believed to have been sailed up the River Deben and dragged a mile up the hill to Sutton Hoo for burial

Later excavations found the remains of a warrior buried alongside his horse under another of the mounds

Mr Brown, who was also a keen astronomer and author of Astronomical Atlases Maps and Charts, had previously been involved in excavating the Roman settlement at Stanton Chair, external, near Ixworth, and Roman pottery kilns in the Wattisfield area, external.

His work caught the attention of Ipswich Museum.

The burial ship was 88ft long (27m) and is believed to have been sailed up the River Deben

When Edith Pretty decided to excavate part of her estate at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge, Suffolk in 1938, she was advised by the museum to call upon his services.

While working on the site, Mr Brown cycled 35 miles (56km) each way between there and his home every week.

Cambridge archaeologist Charles Phillips, who took over the excavation once it became clear it was of huge significance, called Mr Brown "a pure piece of rustic Suffolk" in his book, My Life in Archaeology.

How was the treasure found?

Mr Brown, who is portrayed by Ralph Fiennes in The Dig, focused on three of the mounds, cutting a trench across them and looking for a difference in soil colour that would indicate the presence of an in-filled chamber or grave.

The first dig season revealed signs the mounds has been robbed centuries earlier but there was just enough evidence for a second excavation to be planned at another mound.

It was in the summer of 1939, just ahead of the British declaration of war on 3 September, that he, together with William Spooner and John Jacobs, external, found iron rivets from the hull of a ship, one of only three Anglo-Saxon ship burials discovered in England.

Excavation work at the Sutton Hoo mounds was interrupted by the outbreak of World War Two in 1939

Suffolk archaeologist Basil Brown was assisted by members of Edith Pretty's staff

He wrote regular letters to his wife from the dig, one of which described the ship burial as "a find of a lifetime", external.

An excavation team led by Mr Phillips took over at this stage.

A treasure inquest deemed Mrs Pretty to be the rightful owner of the finds but she donated them all to the British Museum. She died in 1942, aged 59.

The finds spent the rest of the war hidden in a disused London Underground tunnel and were first shown to the public in 1951 at the Festival of Britain on the South Bank of the Thames.

What did Mr Brown do next?

Photographs from 1939 show the extent of the dig which revealed the imprint of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo

During World War Two, Mr Brown worked at Culford School near Bury St Edmunds in a non-teaching capacity.

He managed to continue with his excavation work, says Mr Howgego.

He says Mr Brown would often involve children to help him with his digs and was "really good with young people, and encouraging their interest in archaeology".

Post-Sutton Hoo finds included the Roman Villa at Castle Hill, external in the Whitton area of Ipswich, in 1946.

You might also like:

Mr Brown had been released by Ipswich Museum to complete the Sutton Hoo dig, and after the war he resumed his employment with the museum until he retired in 1961 at the age of 73.

But he continued archaeological excavations until he had a heart attack in 1965, external.

He died on 12 March 1977, aged 89, of broncho-pneumonia at his home in Rickinghall.

Mr Brown's belief that his initial finds in 1938 were of a rich ship burial that had been robbed was confirmed in excavations led by Prof Martin Carver, external from 1983.

They also uncovered the burial of a high-status woman and the remains of a young warrior and his horse.

How is Mr Brown remembered?

The new Netflix production is based on the novel The Dig by John Preston, published in 2007

At the end of the Netflix film, the on-screen epilogue states that the treasures were "first shown to the general public nine years after Edith's death. Basil Brown's name was not mentioned".

"It is only in recent years that Basil's unique contribution to archaeology has been recognised," it added.

After their appearance at the Festival of Britain, the treasures went on display at the British Museum itself in the late 1950s. Mr Brown's name was not mentioned on the information boards.

Sue Brunning, lead curator for the museum's Sutton Hoo collection, external, says: "I don't believe there was any great conspiracy to omit Basil's name.

"The emphasis in the 1950s was very much on the artefacts themselves, which were mind-blowing, but his name has definitely been on the boards since the permanent display was created in room 41, in 1985.

"In fact, the first full published account of the Sutton Hoo finds, written by Charles Phillips in 1940 in the Journal of Antiquity, included mention of Basil Brown, so he was being acknowledged within a year of the dig, even if you would have had to track it down to read it.

"That 1940 archive report has since been made available to read online, external."

Edith Pretty donated the finds on her land to the British Museum, and her name appears with Basil Brown's on the permanent display's information boards

Mr Brown's personal records were originally deposited at Ipswich Museum in 1977 by his widow.

In the 1990s, the Suffolk Archaeology Department started to transcribe some of his notebooks.

Then in 2014, the material was deposited with the county council's Suffolk Record Office, external, with the agreement of Ipswich Borough Council which owns the museum, keeping much of the material together.

The Basil Brown Collection, owned by Ipswich Museum, contains diaries, notebooks and photograph albums.

It also retains a significant proportion of his records from sites that he worked on other than Sutton Hoo.

Mr Howgego says: "Basil was really interesting, and was really interested by finding out new things and getting stuck in.

"He clearly was a person who really loved history and had an emotional connection to the past; he got a kick out of it and was keen to share it with other people."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk

- Published30 January 2021

- Published30 January 2021

- Published17 January 2021

- Published14 January 2021

- Published5 August 2019

- Published24 March 2018

- Published6 October 2018

- Published20 September 2016