Terry Waite: 'I don't know how I survived captivity, but I did'

- Published

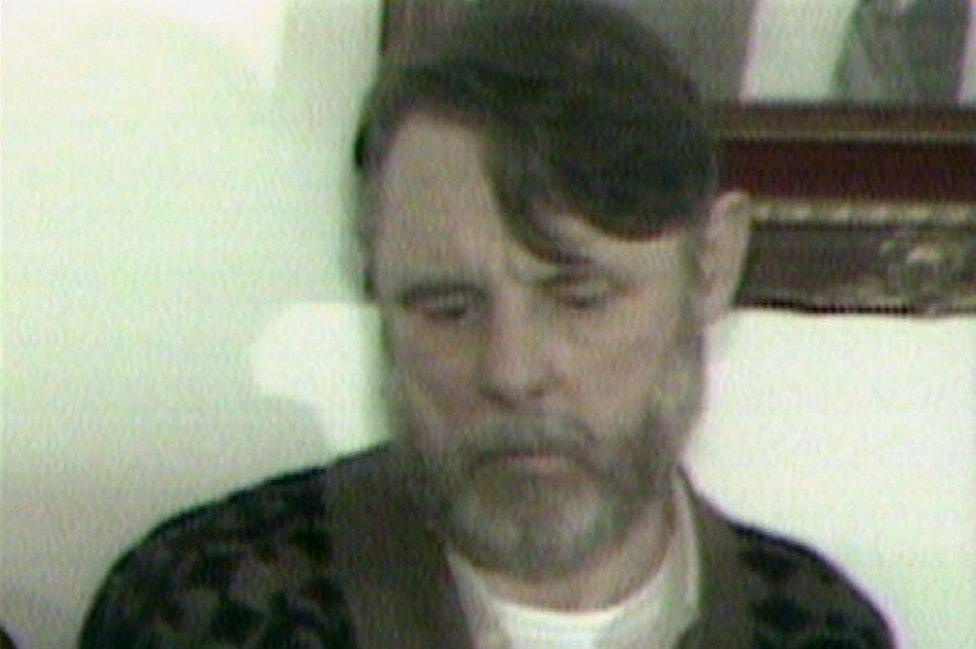

Terry Waite, who now lives in Suffolk, said "plenty of creative things have emerged" from his experience

Thirty years after Terry Waite was released from nearly five years of captivity in Beirut, he said he survived by "keeping hope alive".

The Archbishop of Canterbury's envoy went to Lebanon in 1987 to negotiate the release of several captured Britons - but was taken hostage himself.

Held in "grim" conditions, his Islamic fundamentalist captors freed him on 18 November, 1991, after 1,763 days.

He told the BBC: "I don't know how I did it really. But I did."

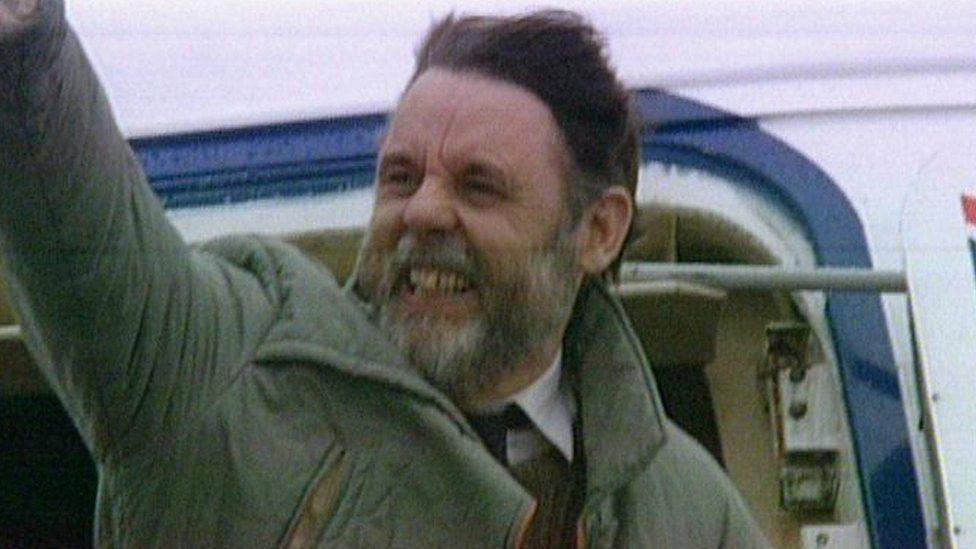

Terry Waite was released on 18 November 1991 after 1,763 days

Terry Waite, now 82, who lives in Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, was working on behalf of Robert Runcie to try to secure the release of several British prisoners, including journalist John McCarthy, when he was captured by Hezbollah.

For much of the time he was kept in solitary confinement, chained to a radiator, beaten and subjected to mock executions.

But he said "by keeping my mind alive and by keeping hope alive" he got through, and wrote many stories in his head, including his first book which he then committed to paper after being released.

He arrived back in the UK at RAF Lyneham to face hundreds of reporters

"The conditions were pretty grim," he said.

"I was chained to the wall for 23 hours and 50 minutes a day, I slept on the floor, I didn't have any books or papers, I was in a room where shutters were put in front of the window so no natural light came in and of course there was no companionship so it was a fairly austere existence - a little bit worse than lockdown.

"But I recognised that I still had life and, although it was very limited, I was still able to live as fully as possible.

"In that situation, you have to learn to live one day at a time."

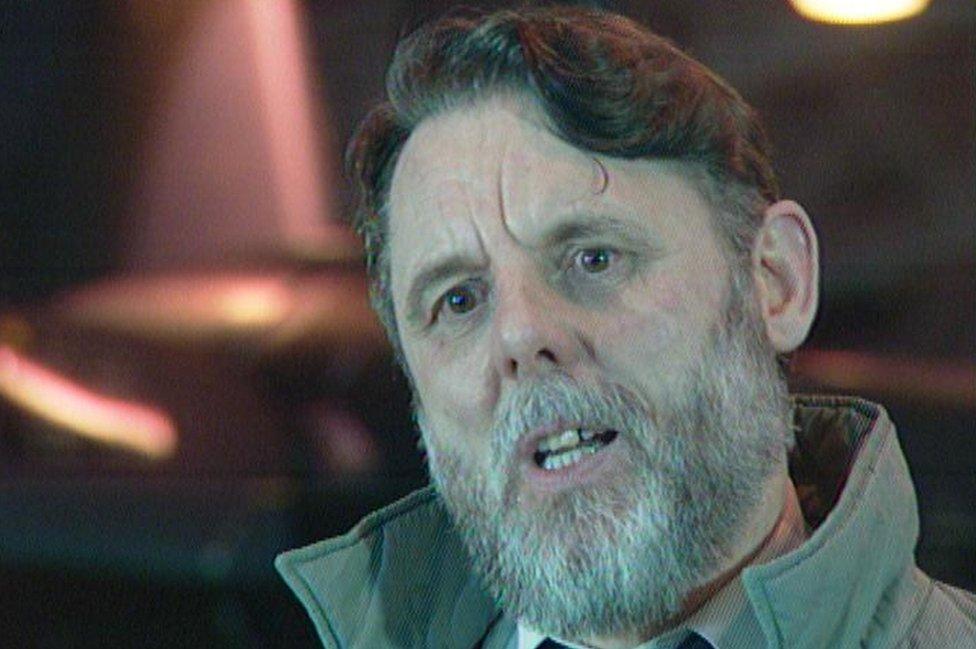

Terry Waite said has lived in Suffolk for about 26 years

He recalled that in his dark cell, there was a chink of light used to come through the shutter in the window.

"Gradually that light illuminated that room and I used to say to myself, "don't give up, remember light is stronger than darkness" and somehow I was able to maintain hope in that situation."

He added that he never questioned his faith.

"I used to say in the face of my captors, you have the power to break my body, the power to bend my mind but my soul is not yours to possess," he said.

"What I meant by that was you're never going to take me completely because my soul lies in the hands of God - and that very simple belief was enough to enable me to maintain hope."

Terry said he can "hardly believe" it has been three decades since his release and while it had "gone in a flash", it took time for him to readjust.

The Archbishop of Canterbury's envoy arrived at RAF Lyneham shortly after being released by his captors

He said since his arrival back in the UK at RAF Lyneham, "plenty of creative things have emerged" from his experience.

"I was determined to make one last speech and then I got away," he said.

"It took me a while, I was very lucky I was elected to a fellowship in Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and was able there to have time away, time to get myself together, but it did take time."

"I'd always had sympathy for people who have been on the margins of life, the homeless, the prisoner, the captive, but during captivity that sympathy was changed to empathy, and that was one of the gifts I got from that experience," he said.

Terry Waite said he was "determined to make one last speech" at RAF Lyneham before "getting away"

He works with the homeless and founded Hostage International, external, an independent charity which works all over the world and advises returning hostages.

"Our advice is that when you come out, yes, certainly make a statement, but then get away and give yourself time," he said.

"Some people don't realise that it really does take time to readjust to life after you've been through a significant period of difficulty in your life.

"I'm very glad that this has been one of the positive outcomes of my incarceration."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk