What happened to the British children born to black GIs?

- Published

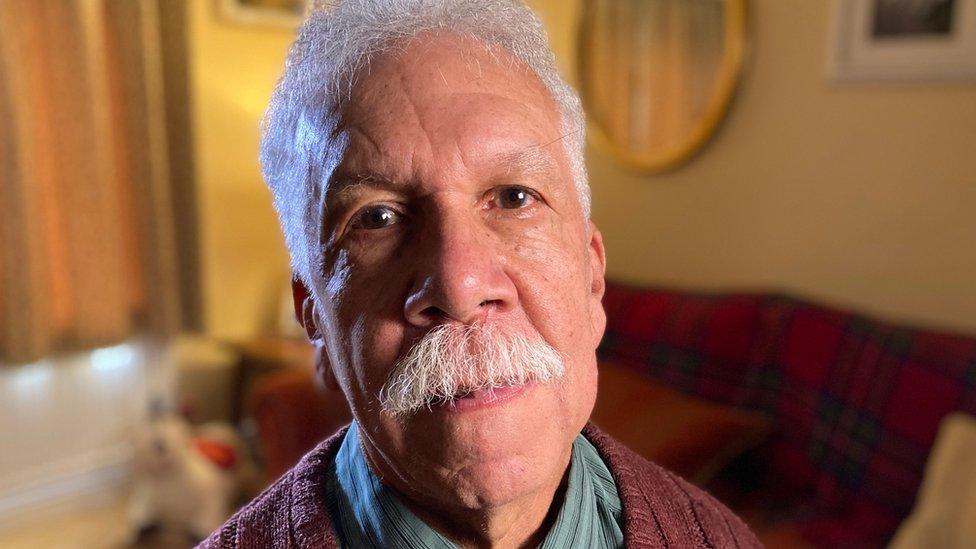

Eldridge says he would have loved to have met his father

Eighty years ago, US soldiers began arriving in the UK to help in the fight against Hitler's Nazi Germany. In a small sleepy village in Suffolk, life was about to change forever.

Best friends Eldridge Marriot and Trevor Everett grew up together in Tostock, where they still live today.

As the pair, now aged in their 70s, reminisce over summers spent playing on the village green, it is clear they have a deep connection.

They were two of 14 children in the village, and about 2,000 across the UK, born to white British mothers and black American soldiers during World War Two.

"We definitely stood out with our curly hair," Eldridge laughs. "But we didn't have any racial problems; we were never treated differently."

"We had some good times and I've had a brilliant life, I wouldn't change it for nothing," Trevor adds.

Eldridge and Trevor bonded as children over having absent fathers who were black US serviceman

As small boys they played in the woods by Tostock Hall, a large house taken over for the war effort, where their fathers were stationed a few years before.

It was very exciting for the village, near Bury St Edmunds, when the soldiers arrived in 1943, Eldridge says.

About 240,000 of the three million US troops, who began arriving in the UK in January 1942, were black.

It was the first time many British people in rural areas had seen a black person.

People living in the village of Tostock in Suffolk were very welcoming to the black US servicemen who arrived in 1943 to serve at the area's military bases

The US servicemen were mainly helping build airbases, such as Lakenheath and Mildenhall, but in nearby Tostock they were asked to look after Italian prisoners of war at the hall.

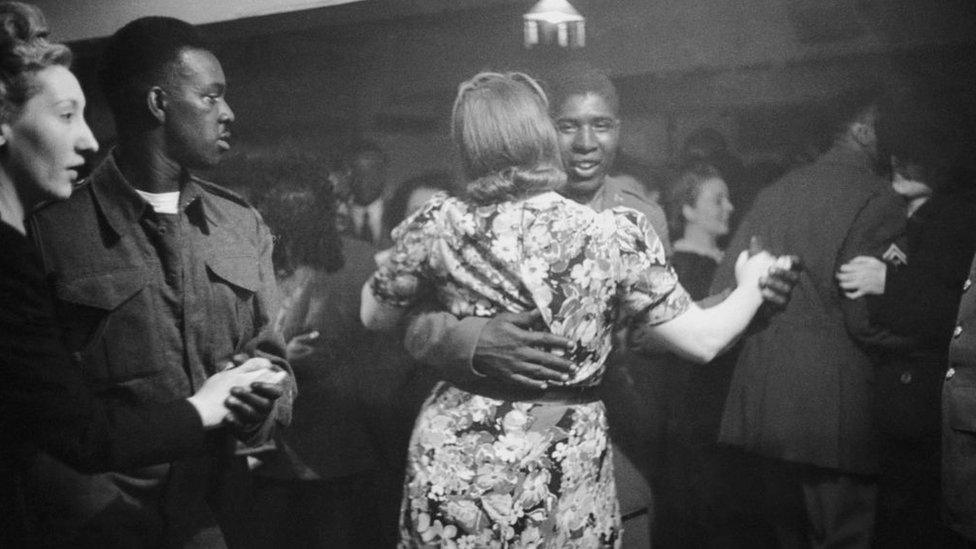

Dances were held at a ballroom attached to the house, where many romances began.

"A lot of them figured they'd got nothing to lose anyway, they could just disappear back to the States," Eldridge says.

His mother Olive was already married to a merchant seaman who was away at war when Eldridge was born in November 1944. Two months later, his father William Ellis - known as Willie - "disappeared to France, never to be seen again".

British authorities tried to discourage relationships between white British women and black troops but many romances began at dances like this one in London in July 1943

When Olive's husband came back and discovered the baby, he said they could only stay married if she put Eldridge into care. Olive refused and they got divorced, while Eldridge went to live with his grandparents.

"My mother wasn't in a position to bring me up," Eldridge says. "She used to come over every Tuesday throughout her life. We never spoke about my father - it was a closed shop.

"My grandfather talked about my father a lot, he liked him. The circumstances were I was left behind and they had to bring me up but they didn't bear any malice at all."

Eldridge's aunt and uncle also lived in the family cottage while he was growing up and he was "spoilt rotten" by them and his grandparents. He later built a house at the end of the garden where he still lives today with his wife.

"All my life I've been on this patch of land. I've had a really good life. It's difficult to see how it could have been any better," he says.

Eldridge's wife had this treasured photo produced for his birthday - a picture of his father Willie superimposed on to a photo of his mother Olive holding him as a baby

Trevor was born a few years after Eldridge and the others, in 1946, after his father Paul Woods left his post in France to go back and visit Trevor's mother.

"He got in a lot of trouble for that. He used to climb up a drainpipe to see her; it was very exciting," Trevor says.

His father, who he describes as "half-Indian, a native American" was born in Atlanta and later moved to Maryland.

Trevor still has seven years' worth of letters from his father to his mother, who brought Trevor up and later remarried.

"My mother used to worry someone would come and take me away so she was ever so protective of me. She used to watch me wherever I went," he says.

Unlike Trevor and Eldridge, many of the babies were put in children's homes

Both men grew up in loving homes but that was not the case for many of the so-called Brown Babies - the term given by the African-American press to these children born during the war.

Black troops were not allowed to marry their pregnant white girlfriends and many of the children were given up for adoption, according to Prof Lucy Bland, from Anglia Ruskin University, who interviewed 50 of them for a book called Britain's Brown Babies.

Many of them experienced racism and were shunned by society, like Babs Gibson-Ward. Her mother told her white naval officer husband that Babs was his daughter, until her skin darkened at six months old and the lie was revealed.

She was sent away from her family in Ipswich to live in a children's home until a foster family came forward, but local children avoided her and teachers refused to educate her.

Babs-Gibson Ward found herself on the streets aged 15 but went on to gain two master's degrees

Speaking on The Localist - Suffolk podcast, Prof Bland says: "Nearly half of these babies were put in children's homes. They were often lied to and told their fathers were dead and that their mothers didn't want them.

"They were often called names and didn't understand. Some of them didn't even realise they were a different skin colour; no-one was explaining it to them."

Very few of them were adopted. Officials said it would be impossible to place mixed-race children and the government blocked adoptions from the US, worried they would be seen as dumping them there.

Leon Lomax was one of only a few of the children who went to the US to be brought up by his father, Cpl Leon Lomax.

He arrived back in Ohio at the end of the war with a confession for his wife Betty - he had fathered baby Leon, who was born in Chelmsford, Essex in December 1945.

Leon Lomax's arrival in the US in January 1949 was heralded by the US media as the first "Brown Baby" to reach home, but the British government blocked other adoptions, despite great demand

"As a kid I wondered 'why hasn't my mum tried to find me?,'" says Leon, speaking on the phone from his home in Ohio.

He had a difficult upbringing with his father, who never told him who his mother was or even that he was mixed race.

"I figured I was just black basically," he says. It was only when he had children of his own that he decided to find out more about his heritage.

Leon managed to trace his mother to England, but sadly she had died two years previously.

"I found that I had a sister, Pauline. She said our mother was always nervy around Christmas time and Pauline didn't know why, but I was born on 17 December. My mother never shared anything with her about me," he says.

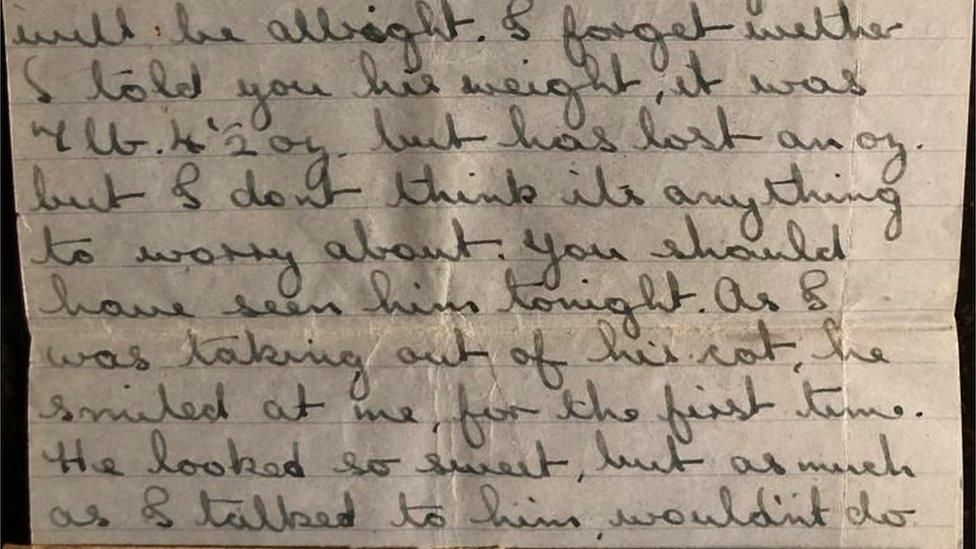

He recently found a letter his mother had written to his father 75 years ago, detailing her visits to him in the children's home before he was flown to the US.

"She wanted to keep me but could not afford to. I smiled at her for the first time and she was really happy," he says, his voice thick with emotion. "I cried when I read that. It closed a circle for me."

Leon's mother sent his father a letter saying he had smiled at her for the first time

Trevor and Eldridge both decided to trace their fathers when they grew up. Trevor traced his to the US in 1987 with the help of the Red Cross and flew out with his family to meet him.

"He worked in a military hospital and he took me to meet all his friends - he was proud. He used to say he had a son in England, but nobody would believe him."

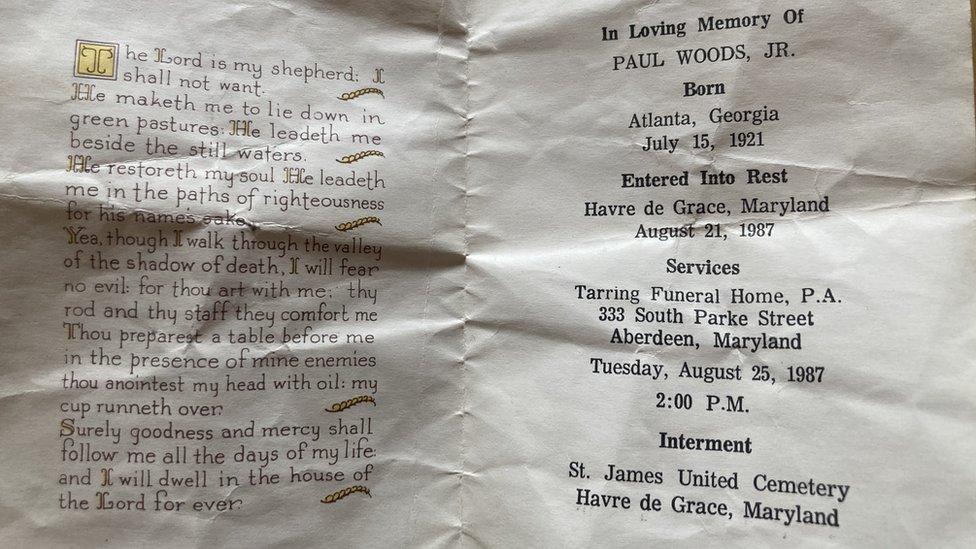

Trevor spent two days with his father, who was then aged 68, but tragically on his third day out there, his father died.

"I was waiting for ages in this hotel and I thought he didn't want to know anymore," Trevor says. "But then his friend drove up and said 'we've got some bad news, your father died in the night'.

"He died in his chair. They said he died from being overjoyed."

Trevor keeps this funeral notice for his father in his wallet

Trevor was pleased to be able to attend the funeral but wishes he had got a photo of them together before he died.

"I didn't get the chance to ask all the questions I wanted to ask," he adds.

Eldridge recently traced his family to Los Angeles, but his father had died in 2004 at the age of 89. He discovered a half-sister called Elsie who was born before him and didn't know of his existence.

"She wasn't really shocked," Eldridge says. "Our father used to tell her he enjoyed his time in Europe. She still lives in the same house as he did.

"Elsie says I look just the same as he did when he was in his 70s," he adds.

Eldridge had always presumed his father was married with children so he didn't attempt to make contact earlier, concerned he would "intrude and spoil his life".

"He was married to his wife for 60 years and kept me a secret all that time. There was nothing he could do. He couldn't say what he had done."

Eldridge says he would have loved to have met him and asked about his time in Tostock.

His son is going to LA to meet Elsie and her family later this year and Eldridge is excited that they are all planning to come to Tostock next year.

And finding Elsie has solved a mystery that has puzzled him for his whole life.

"I always knew my mother in deep Suffolk would never ever have called me Eldridge, and I thought it must come from my father [Willie Ellis]," he says.

"Eldridge was his name at birth. So he obviously picked my name.

"It's a bit unusual, isn't it?" he adds proudly.

Hear more about the story of the Brown Babies on The Localist - Suffolk podcast on BBC Sounds.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published17 May 2019

- Published3 November 2012