Anthony Ogogo: 'When I started boxing I was an angry little boy'

- Published

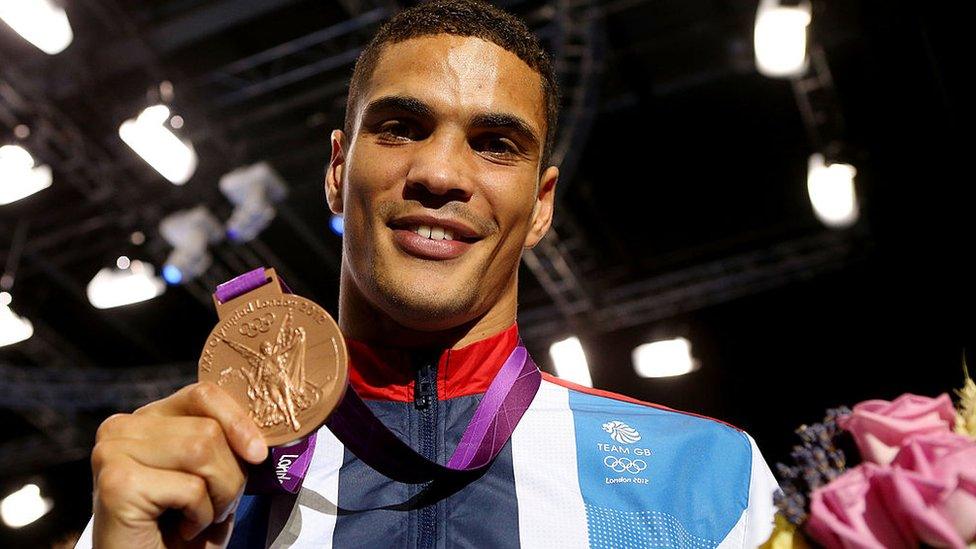

London 2012 Olympics bronze medallist Anthony Ogogo shares his experience of growing up in Lowestoft, Suffolk

Former boxer Anthony Ogogo was born to a white English mother and a black Nigerian father. Here in his own words, he reflects on his extraordinary journey from growing up in the UK's most easterly point to Olympic success at London 2012.

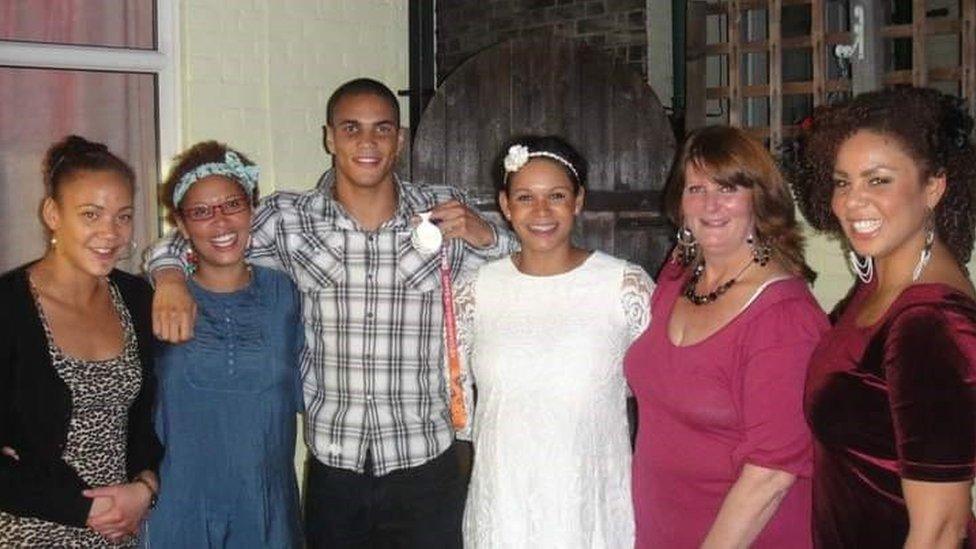

Ogogo says his mum Teresa ensured he and his four sisters had a "sense of identity" and understood their Nigerian roots

My dad is the reason why I have this beautiful skin.

My dad is the reason why I have this amazing last name.

But he never taught me anything - he was never here, he was never around.

I was born in Lowestoft but my dad was Nigerian, lived most of his life there and came over here [for] education.

He wasn't much part of [my] life growing up but my mum knew it was very important for us to have a sense of identity, understand why we look what we look like and why our last name is Ogogo and what that means to us.

She instilled that in me, which is weird because my mum is a white lady from Lowestoft, Suffolk.

Ogogo says his father, who was also called Anthony Ogogo, was not part of his life when he was growing up

In my teenage years, I had a lot of anger towards [my dad] - a lot of borderline hatred actually.

We were in Suffolk and he was in London.

He would come back at weekends and he'd start on me - he'd tell me off and I'd done nothing wrong.

He'd hit me, my mum would protect me, then he'd argue with my mum and then he'd get in his car and drive away - this happened for a long, long time.

You might also be interested in:

As a kid, it felt like they were arguing over me.

For my entire life I thought they got divorced because of me, that really messed me up.

So, as a teenager I was just focused on me, on boxing and being successful.

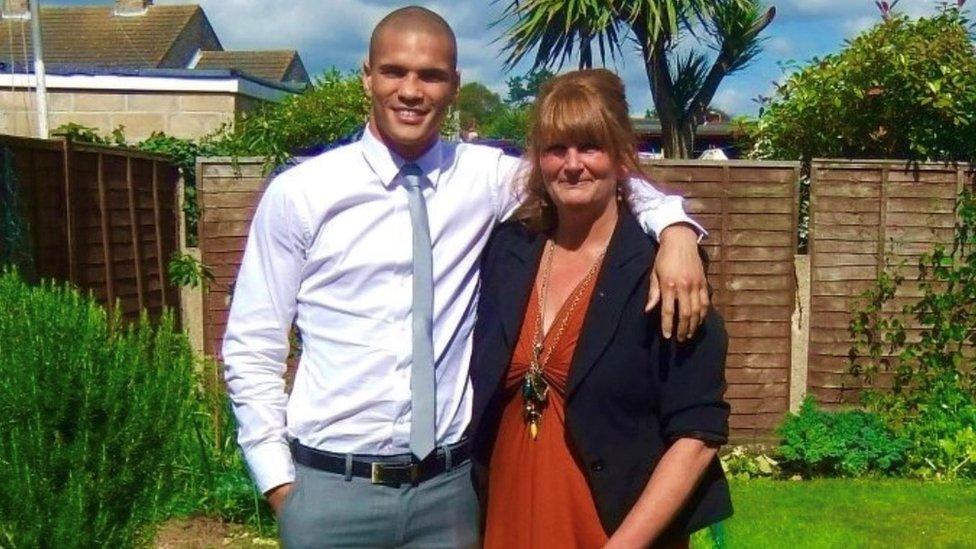

I saw my mum struggle, I saw her work her backside off to provide for us, so I was very much driven at being successful to make her and my whole family proud.

He says he "didn't see anybody else like me, other than my sisters" when they were growing up

It wasn't until my dad died that I said to myself that I did want to know more about my heritage.

He died when I was 23 and I didn't want to go and see him at hospital, didn't want to go to his funeral, that's my one regret in my life.

But it wasn't until he died that I realised the hatred had started to dissipate and I was like: "Do you know what? He was an inspiring man."

He was the oldest of 10 brothers and sisters, he provided for his family, he had a PhD, he was a very good man and ultimately as children we look to our parents like these superhero people.

I still do with my mum - but he was just a human and he had his flaws.

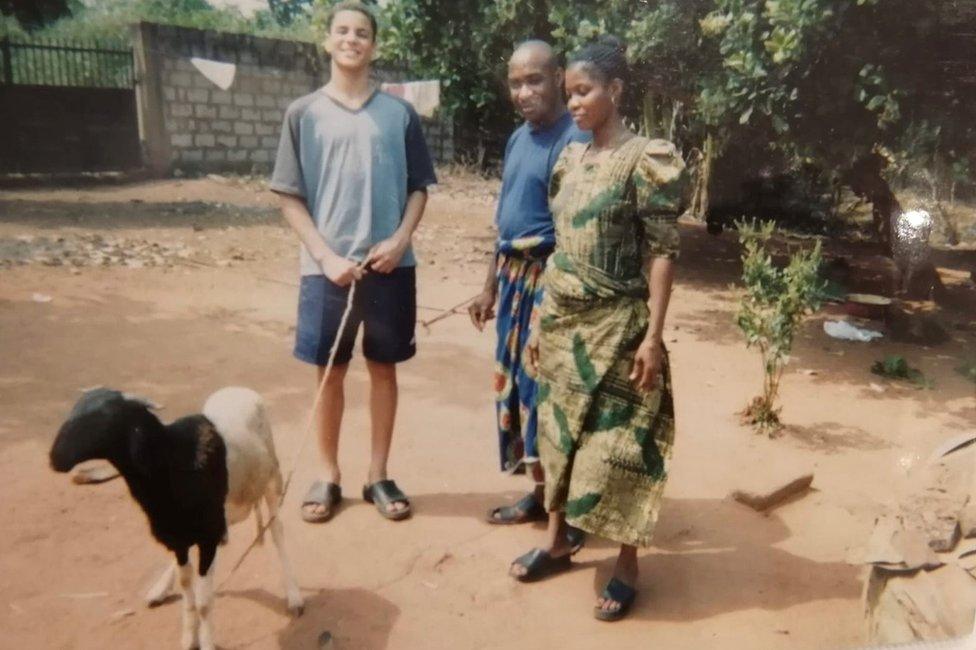

Ogogo, pictured with his uncle and cousin, visited Nigeria as a young boy

Nigeria is a place I've been longing to go back to for years, it was the first country I visited.

Lowestoft is the most easterly point in the UK, that's our little tag line, but what that means is it's [difficult] to get to, nobody goes there, it's [difficult] to get from and nobody leaves.

When I was 12 or 13 years old I went to Nigeria and, wow, what a culture shock.

Ogogo says he sees his mum Teresa, who had a brain aneurysm in the weeks leading up to the London 2012 Olympic Games, as a "superhero"

When I started boxing I was an angry little boy. I was in trouble at school a lot of the time, but boxing was the perfect vehicle for me.

In boxing, I was a warrior, when the bell went, I went into this place where I was so determined and driven to win.

I was a very good footballer but boxing gave me something different that football didn't give me.

I loved [the fact that] when I won, I won. When I lost, I lost - I didn't lose because the goalkeeper made a mistake or the left-back wasn't paying attention. I lost because I needed to get better.

I had the responsibility and I loved taking control of the situation.

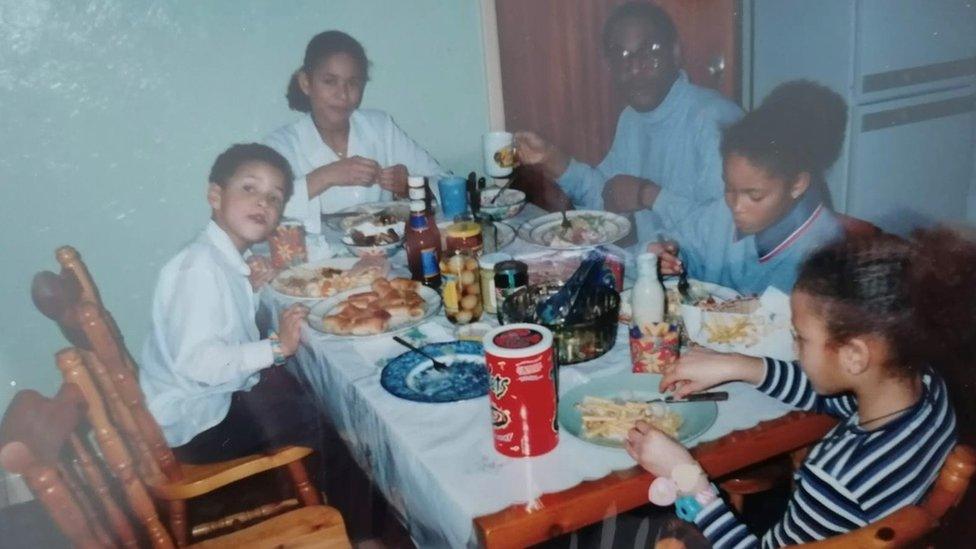

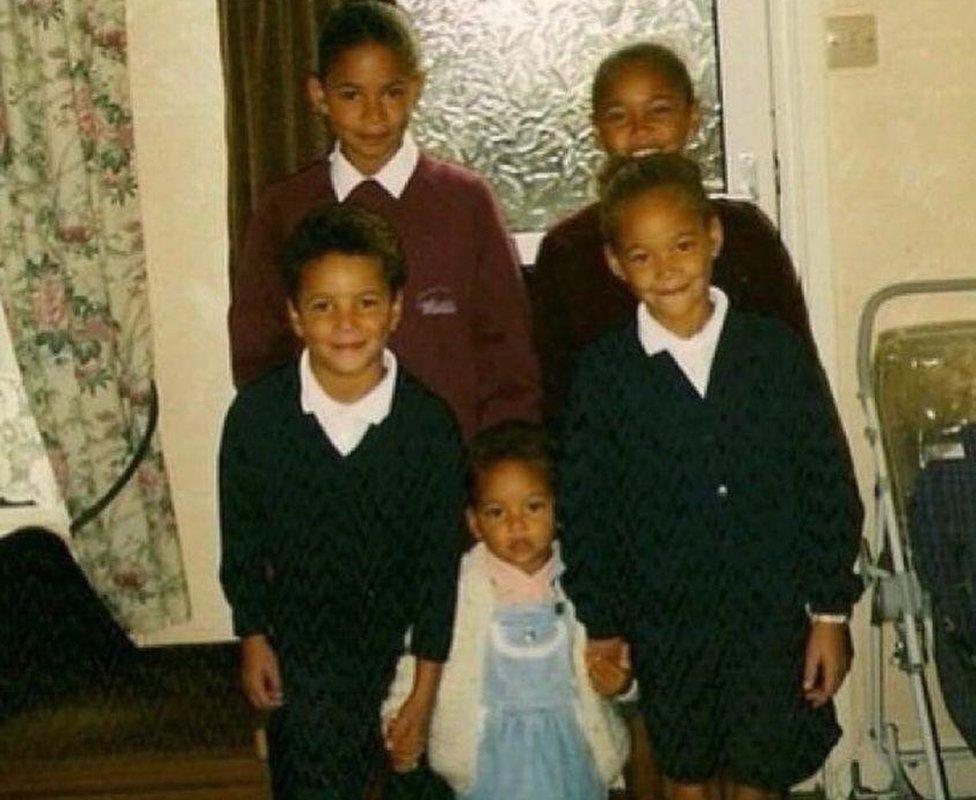

Ogogo, front left, grew up in Lowestoft with his sisters, clockwise from top left, Leanne, Joanne, Toni and Carly

But all the cards were stacked against me. I was from a family full of women - my mum and my four sisters - [there was] not one ounce of male testosterone in my life other than the boxing coaches.

I was from the most unfashionable town in the country, from an unfashionable county in the country.

Where I'm from, people don't go to the Olympic Games, people don't become successful.

Where I'm from, you're a success if you work offshore and earn £50,000 a year.

If you want to be a sporting star then you come from London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, that path has been walked a thousand times before.

When you want to become an international boxing superstar from Lowestoft, Suffolk, it's like: "How do I even do it?"

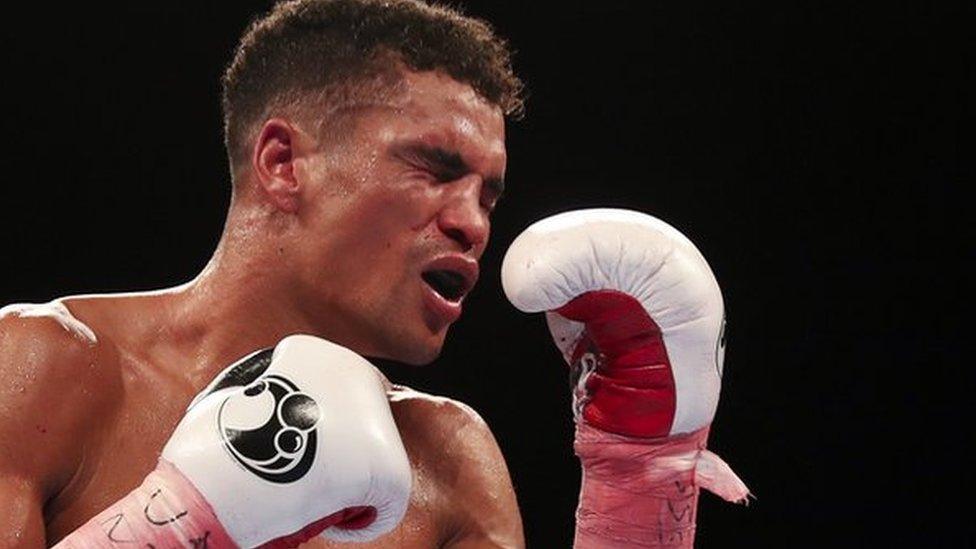

The Lowestoft star beat the then world number one at the 2012 Olympics before losing in the semi-finals

I also found I never fitted in anywhere.

I was one of a handful of black or brown faces in Lowestoft growing up, I didn't see anybody else like me, other than my sisters.

My best friend called me a name when I was four or five years old and that was the first day I realised I was different.

I went home, got a flannel and washed my face as hard as I could, I was sobbing.

When my mum saw, she asked me what was wrong and she told me: "You're beautiful, you're brown and don't ever, ever say that again."

Ogogo suffered a fractured eye socket in 2016, an injury that forced his retirement in 2019

Then when I first got on to the England team.

I was 14 years old and I travelled down to Crystal Palace with my bags on the train. [It was] a four-hour journey to get there.

I finally got there and thought I'm now going to make some friends, some black friends, people like me.

I turned up and there was a little group of black boys and I thought I had found my community.

It was 2003 and England had just won the Rugby World Cup; I didn't know anything about rugby but we watched the final, I knew we won and my mum bought me a rugby shirt.

So there's me, wearing my rugby shirt, proud as punch, and they were like "do you like rugby?" and I went "yeah, I guess" and they chuckled and walked off.

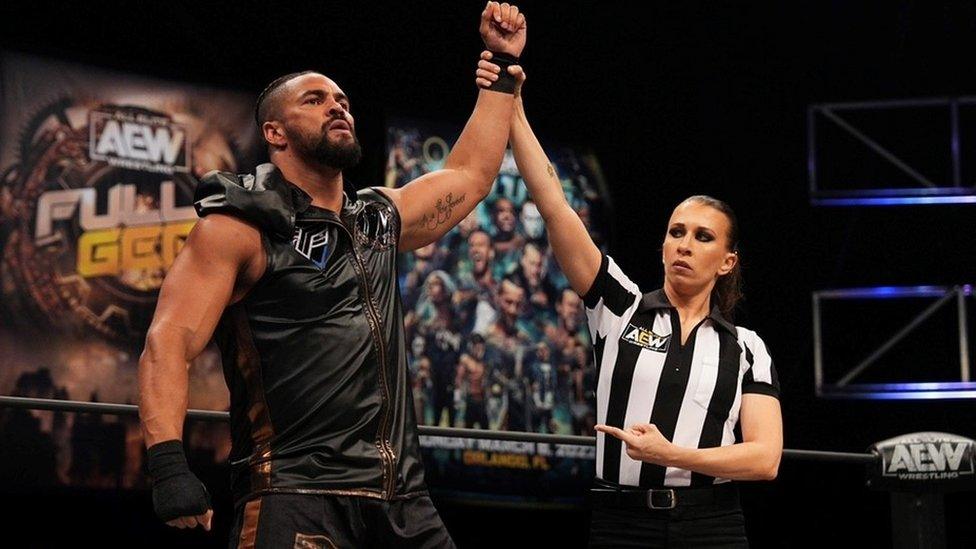

Ogogo made the switch to wrestling after retiring from boxing

Then I realised rugby is a white, posh person's sport. I had no idea.

So it transpired I was too black for the white kids and too white for the black kids. I just didn't fit in anywhere and that was hard for me.

But from that moment, I made a vow to myself then that if I'm not going to fit in and I'm going to stand out anyway - watch how much I stand out, watch what I do with my life.

As told to Angelle Joseph for Belongings on BBC Radio Suffolk. Words by Kate Scotter.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published25 March 2020

- Published28 July 2019

- Attribution

- Published11 March 2019