Care worker shortages: What is it like working in the industry?

- Published

Latest figures show the number of care workers in England fell for the first time and the number of empty care jobs rose by 52% in a year

Thousands of carer roles are unfilled in England and the overall number of care workers is falling, leaving more people without support. What is it like for those working in the industry and why are some choosing to stick it out, while others leave?

Debra Parnell says some carers leave after a week because they realise it is "not an easy job"

"We don't do this job for the money, we do it because we enjoy what we do," says Debra Purnell.

The carer of 50 years runs a care company in Daventry, Northamptonshire.

Like many businesses similar to hers, she is finding it harder to retain staff.

She says it is "not an easy job" and some people leave after only a week when they realise the amount of hard work involved.

Her hope is for the government to give carers more recognition and funding towards training.

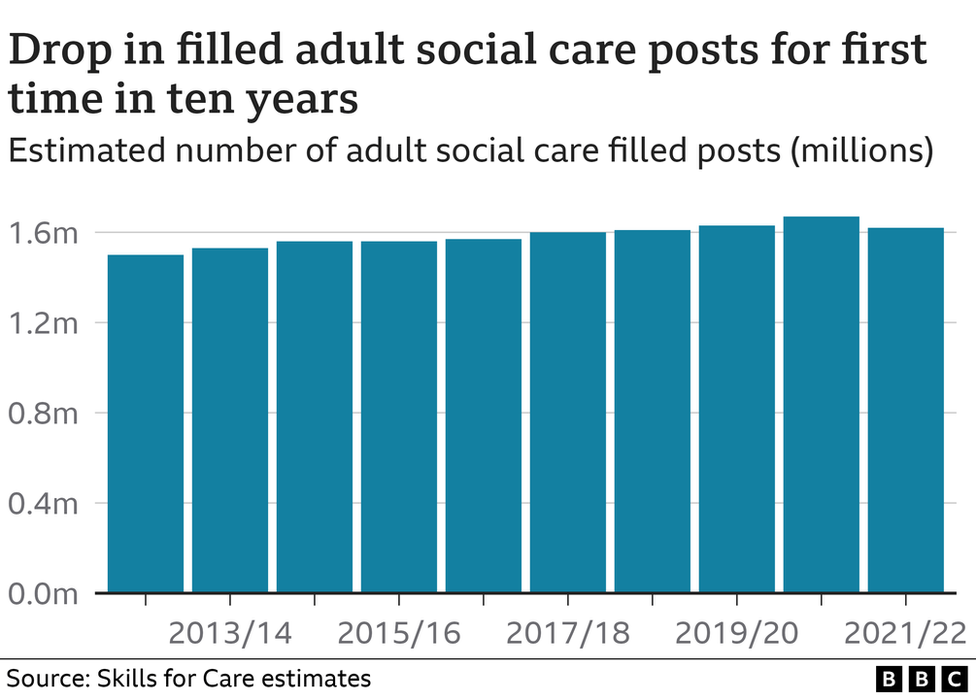

Latest figures, external, published in October, show the number of care workers in England fell for the first time and the number of empty care roles was up by more than half.

The industry body, Skills for Care, found in the year to March 2022 there were 1.79 million posts in adult social care, of which 165,000 were vacant - a rise of 52% on the previous year.

It said the number of filled posts fell by 50,000 compared with the previous year - the first drop ever.

These figures referred both to staff in care homes and workers who support people in their own homes.

Nicole Greenaway, 24, says being a carer is a job she enjoys

Among Ms Purnell's workforce is carer Nicole Greenaway.

The 24-year-old from Crick says she wanted to work in the sector after being a carer for a family.

Since starting the role two years ago, she enjoys the satisfaction of helping people with their day-to-day needs.

"You're their extra limb and you're there just for conversation and the chat and housework and so forth.

"I would say we could probably do with more recognition from the government because we are doing an amazing job as it is, but it's a job I enjoy more than anything," she says.

'People don't understand how hard it is'

Emi Iancu, 31, worked in a care home since 2019 but left in December to work at Felixstowe docks

Emi Iancu, of Ipswich, started working in a care home in 2019 and says at first it was a "pleasure to go to work".

But the 31-year-old says after the pandemic and Brexit,it started to be "more difficult" and he was effectively doing "two jobs in one night".

Married father-of-one Mr Iancu says he left his job as a carer in December to work at Felixstowe docks as a tug worker where he now earns £13,000 more.

Mr Iancu says he can afford to provide for his wife Laura and their two-year-old daughter Ayla better since quitting his job a carer

"Working with residents was very rewarding, very nice, but sometimes I had hot cups of tea spilled on me, I was punched and slapped.

"People don't understand how hard it is".

Mr Iancu says other members of staff would breakdown as they were struggling to cope with the workload and he was often a shoulder for them to cry on.

Mr Iancu says he was doing effectively two jobs in one night when he worked as a carer

Mr Iancu says his new job at the port gives him the opportunity to save money and provide for his wife Laura and their two-year-old daughter Ayla.

He says wages for care work are "ridiculous" and the pay needs to be increased to attract and retain people.

Although he has left the industry, he says he might one day return to work as a carer.

"It all depends what's happening in the future," he added.

'People are leaving in droves'

Tina Judd was a community carer for 18 months and left last August

For Tina Judd, she found working as a community carer took too much of a toll on her physical and mental health.

But the 55-year-old from Henley, near Ipswich, remains in the care sector.

She became a carer because she lost her mum five years ago and had loved looking after her.

After 18 months in the role, however, the "very busy, very long and unsociable hours" took their toll.

She says "hidden problems" added to the pressure, including traffic jams, roadworks and diversions between calls.

Ms Judd went into caring because she lost her mum five years ago and she says she "loved caring for my mum"

Ms Judd decided "enough was enough" when she was "too exhausted and too shattered" to enjoy time off.

She decided to take a job in sheltered housing instead which she describes as "absolutely wonderful".

Ms Judd says she is also financially better off.

"The amount of money people get paid in care is terrible, especially with the amount of responsibility they have... all the rushing around.

"In some places they offer literally minimum wage to work there, it's no wonder people are leaving the industry in droves," she says.

Ms Judd says it was a "very difficult" decision to leave community care because the clients "become part of your family and you become part of their family".

But she says: "Life's too short not to make the most of every single day that you have."

'Biggest funding increase'

The government says social care was prioritised in the Autumn Statement, making up to £7.5bn available during the next two years to support adult social care and discharge.

It says it was the "biggest funding increase in history" and would allow more people to access "high quality care and help address challenges including; waiting lists, low fee rates and workforce pressures".

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson adds: "We're promoting careers in care by launching our annual domestic recruitment campaign and investing £15 million to increase international recruitment of carers."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published5 February 2023

- Published30 January 2023