The mothers supporting each other through child separation

- Published

Penelope says she counted every single day after her daughter was taken away until they were reunited

Some 21 years ago Penelope's heart broke into pieces and it has never fully healed, she says. Her four-year-old daughter was taken away after a court ruling, leaving her bereft.

"She was my entire world, I absolutely adored her," she says.

Penelope, now 58, met her daughter's father while she was living in France, and had moved back to Norfolk alone to bring up their child.

But she was struggling with her mental health and her mother was dying from cancer, leaving her with little support.

"I asked for help. I wanted to go to a mother and baby home, but I wasn't given the funding," she says.

Penelope came to the attention of social services and her case ended up in court, where a judge decided her daughter should be put up for adoption.

"I was told she could come to emotional harm," she says. "I knew I was a good mother and I didn't deserve this."

Penelope takes part in art therapy sessions to help process her enforced separation from her daughter, which has devastated her life

Penelope, who now lives in Suffolk, insists she was not in a fit state to defend herself because the court case was the day after her mother died. She tried and failed to appeal against the decision.

"I know I could have brought my daughter up with the right support. I did everything in my power to keep her. I spent my life savings in court trying to get her back," she says.

Five years ago, Penelope started going to Beam, a support group in Suffolk, external run and attended by women coping with enforced separation from their children.

"There is a great empathy and understanding between us, which I haven't experienced with anyone else," she says.

The charity runs wellbeing courses, coffee mornings, trips to the zoo and beach, and art therapy sessions, which allow Penelope to release her "anger, tensions and fears".

Not long after joining Beam, Penelope's daughter traced her.

"She called me on her 21st birthday. I had been waiting for that phone call for so many years," says Penelope, breaking into a smile.

"It was the answer to my prayers. I counted every single day we were apart. I never stopped thinking about her. I love her to eternity and back."

Donna's three children were taken into care but Beam has helped her maintain a relationship with them

Seven years ago, Donna started attending the charity, where her affectionate nickname is "naughty Donna".

The 38-year-old hospital cleaner now helps run the coffee mornings and has become an ambassador for Beam, which she says has given her a huge confidence boost.

"I was sad, depressed and anxious before I started coming here," she says. "I understand the heartache the other women are going through. I like cuddling people. It makes them at peace and it gets them smiling again."

Donna was in an unhappy relationship which professionals wanted her to leave, when her three children were removed and taken into care.

Donna says the other women who go to Beam have helped her feel better about her situation because they understand how it feels

She says her heart was "ripped out" by the decision.

"I love my children with all my heart. I felt lonely, I just thought they should be with me. I felt like it was my fault and I shouldn't have stayed in that relationship," she says.

Beam has supported Donna, who has a learning disability, to maintain contact with her children and she is now in a relationship with a "kind, loving and caring" man.

"I was so nervous when I first started coming here. I thought people would judge me, but we all support each other," Donna adds.

Former barrister Cherie Parnell founded Beam in 2015 after years working in the family law courts, where she often represented mothers who would lose their children to the care system.

She realised there was nowhere for these women to go for support.

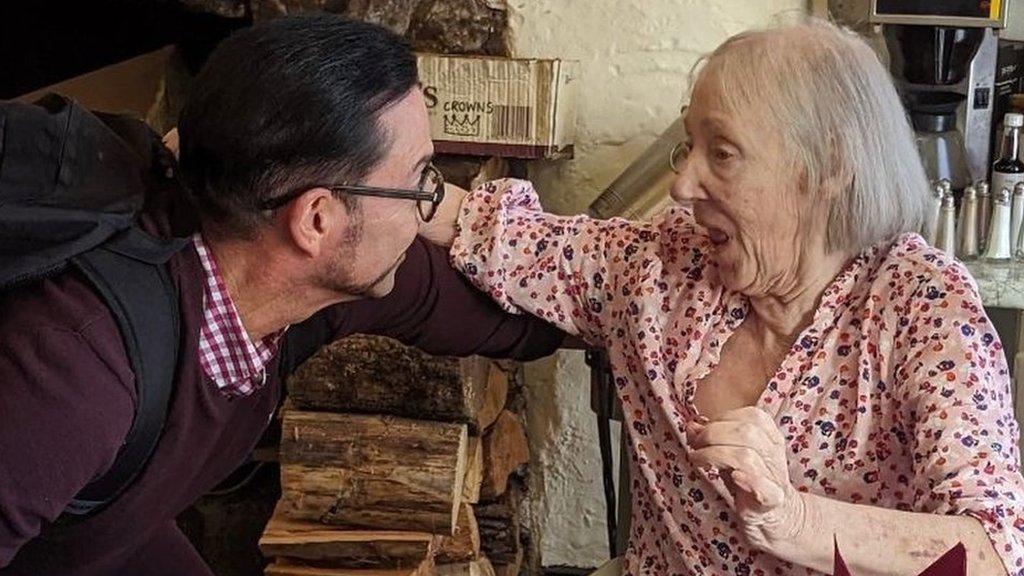

Cherie was a successful barrister before she gave up her career to start the charity

Many of the mothers were domestic violence victims, while others had been suffering from mental health issues like post-natal depression.

Some had made mistakes, she acknowledges, but she believes many could have brought up their children with the right support.

"A toxic mix of grief compounded by shame keeps them isolated and stuck in destructive cycles," she adds. "They are forgotten women; they are hidden."

Cherie felt she could no longer leave them at the end of a court case "with a handshake and an expression of regret" and she made the decision to leave her job.

"I thought it would only be for around a year. I didn't want to leave, the money was very good, but this was a calling," she adds.

Art produced by the group of mothers, who meet weekly in Ipswich

Cherie says when women first come to Beam they are "so clearly hurt and ashamed" but love from their peers allows them to flourish.

Many are supported to get jobs, degrees and, most importantly, to form a relationship with their children.

Beam currently helps 50 mothers in Suffolk, and others across the UK through online groups, but Cherie says there is a desperate need for similar groups elsewhere.

Why do children get taken into care?

Abuse or neglect was the most common reason children were taken into care in 2022

There were 82,170 children in care in England last year compared to 75,360 in 2018, according to the Department for Education.

Abuse or neglect, including domestic abuse, was the most common reason children were removed in 2022, accounting for 66% of cases. Family dysfunction was the next most common, named in 13% of cases, followed by family in acute stress (7%), parental illness or disability (3%), and the child's disability (2%). Around 90 children were taken into care due to the family's low income last year.

Prof Karen Broadhurst, from Lancaster University, has spent 25 years researching child and family justice. She says many children come before the courts because of "maternal unmet needs".

"There is not enough support for mothers to leave relationships of domestic abuse, or to access help for mental health issues and substance abuse," she says.

"The courts, which are already overloaded, are under pressure to get through the cases in 26 weeks, so there often isn't enough time to work with even the most motivated parents who want to get help.

"We do see pockets of really good practice, where intensive support services work to reduce repeat removals from families, but many local authorities simply don't have enough money to scale these projects up."

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care said mothers can benefit from NHS talking therapies and it has allocated an additional £2.3bn a year for the expansion of mental health services in England.

Cherie believes that, once you have established a place of safety and love, it can be transformative for the women.

"The love is healing and they suddenly have hope for the future," she says.

"I thank God every day for the opportunity to be involved in the lives of these amazing women. They have brought so much joy into my life.

"If you can change the life of one person... what a legacy."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published8 March 2023

- Published5 February 2023

- Published15 July 2022

- Published22 November 2021

- Published23 September 2021