Jack Phillips: Boy from Godalming became Titanic hero

- Published

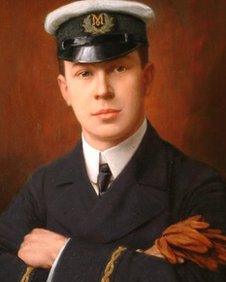

Jack Phillips by Martin Ellis. Picture: Godalming Town Council

For a young man from a Surrey village, being promoted to chief wireless telegraphist on the new luxury liner Titanic was a source of great pride.

The son of a draper, Jack Phillips operated the most modern and powerful wireless equipment of any merchant ship of the time.

But before the doomed vessel sailed, he told a friend he would have preferred to be aboard a smaller ship - for Jack had a dread of icebergs.

Nonetheless his actions in the early hours of 15 April 1912, as Titanic sank in the Atlantic, ensured that he was remembered as a hero of the disaster.

He stayed at his post, sending out the distress calls and advising on the latest position of the ship until it foundered.

His last message was picked up by another ship, the Virginia, at 02:17, three minutes before the stern sank.

His body was never found and it is believed he went down with the liner.

"He was a tremendous hero at the time," said Alison Pattison, curator of an exhibition about Phillips at Godalming Museum.

"His messages brought the Carpathia to people in the lifeboats.

"That is the reason they survived. Otherwise they would have died of exposure."

The Jack Phillips Memorial Cloister in Godalming has been restored with National Lottery funding

In all, 705 people were rescued, though more than 1,500 perished.

Phillips was born and grew up above the shop where his father worked in Farncombe, near Godalming, and his first job was at the local Post Office, where he learnt Morse code, before moving on to Marconi.

He was 25 on 11 April 1912, the day after Titanic set sail from Southampton.

But although he is remembered as a hero, his role is not without controversy.

Two warning messages of icebergs from other ships in the area were not passed on to the bridge - Phillips was concentrating on handling messages for passengers.

"There is a lot of controversy about the whole sinking of the Titanic... everything from the quality of the rivets to the messages that Jack and his assistant Harold Bride received," said Ms Pattison.

"Something we really want to do is to put that in context and remind people that when it came to it, Jack behaved with extraordinary heroism.

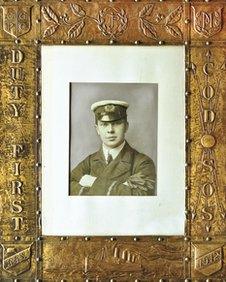

The Post Office memorial to Phillips, made by his headmaster Charles Elworthy

"He sent messages from the moment the captain first told him the ship was going down and he stayed at his post, even when the captain told both the radio operators they should save themselves.

"Harold Bride left at that point and he did survive, but Jack wouldn't go."

Since the exhibition opened on 6 March, thousands of people have visited and learned Phillips's story.

"The reaction has been really wonderful. It is unprecedented - really remarkable," said Ms Pattison.

Ms Pattison said children were among the most enthusiastic visitors, enjoying activities such as dressing up and trying to guess whether their outfits were for first class or steerage passengers.

"Children are fascinated," she said.

"It is quite an old fashioned story - about duty and how a young boy from a small Surrey village found himself in such an impossible situation and ended up such a hero."

- Published11 March 2012

- Published20 October 2011

- Published11 July 2011

- Published23 June 2011