'I know pilots who are driving for Sainsbury's now'

- Published

Passenger numbers have fallen by more than 80% at Gatwick due to coronavirus

Crawley flourished while nearby Gatwick Airport grew, but the town now faces gloomy forecasts of widespread unemployment and deprivation as the aviation industry struggles through the coronavirus pandemic.

Louise Crunden has applied for 72 jobs in the past two months and she is starting to lose hope.

"You think what's the point of even getting out of bed," she said. "If you're lucky you get a rejection letter; if you're unlucky you get ignored."

Louise Crunden: "Where I live so many of us have all been ditched"

The 54-year-old graphic designer was made redundant by an airport parking company in August as bosses tried to cut their wage bill during an unprecedented and sustained fall in air travel.

She is not alone.

From cabin crew to cleaners and baristas to baggage handlers, more than 6,000 people, external once made the short commute from her hometown of Crawley to Gatwick Airport. Many more are employed by local businesses, like airline caterers and B&Bs, which rely on the airport and its customers.

So, when coronavirus restrictions led to a precipitous drop in passenger numbers, work soon dried up.

In August it was revealed that 25,800 people in Crawley were on furlough, external - at 41% it is among the highest proportion of workers in any part of the country. Others have already lost their jobs, and unions fear more redundancies will follow.

"It's terrible out there," Ms Crunden said. "The real people are suffering. Where I live so many of us have all been ditched. I know pilots and all sorts who are driving for Sainsbury's now."

In total, more than 23,000 people worked at Gatwick, where several thousand jobs have already been cut or are earmarked for redundancy this year. But by some estimates, external the airport directly or indirectly supports a further 60,000 jobs - and it is unknown how many of those will be lost.

Gatwick predicts it will take four to five years to recover

Airlines predict business will not return to normal until at least 2024, while local politicians and union officials fear that, without further government support, Crawley will suffer mass unemployment and deprivation that could last generations.

Ms Crunden, who has three decades' experience in graphic design, has applied for jobs as everything from a supermarket assistant to a PCSO.

"At 54, people are just not interested in you," she said. "I'm either too experienced or not experienced."

But she counts herself lucky, having recently discovered she can cash in a pension scheme early. "I went to bed and cried [after finding out]. I thought, I'm going to get through this. I don't need to lose my house."

Abigail Kelly lost the chance of her "dream job" due to the coronavirus restrictions

Early retirement is not an option for Abigail Kelly. The 20-year-old was nearing the end of cabin crew training in March when she was made redundant over the phone.

"I just started crying," she said. "I was in hysterics."

She couldn't afford to be out of work for long. "We were panicking, because we have to fend for ourselves, so we were worrying about rent, food, loans, everything."

Having borrowed money to pay the bills, she eventually found a job in a call centre, selling insurance. "I lost the opportunity to do my dream job to sit in an office for seven hours a day cold-calling people, receiving abuse," she said.

She has now started work as a childminder's assistant and is considering retraining, but money remains tight and she fears she will soon need to borrow again.

"It's a constant, vicious cycle of being in debt and trying to pay it off," she said.

Jon Best: "I have got to sell blades of grass off the lawn if I can"

Jon Best is also struggling. The 54-year-old, who runs a B&B less than two miles from the airport's south terminal, said business had been "absolutely dire" and the B&B was "running about £3,300 a month short".

But it's not just his livelihood - and his home - at stake. He recently piled his parents' life savings into an extension and a separate residence for his widowed mother, who has cancer and must be shielded from his customers.

"If I was to lose this [business], my mum would lose everything my dad ever worked for, so I am in a really tough situation," he said.

"I have to do everything I can," he said. "I have got to sell blades of grass off the lawn if I can."

During lockdown, when flights were essentially grounded, his business was kept afloat by government grants. But while some industries have bounced back, hospitality around Gatwick is crippled by travel restrictions, he said.

"The thing that's really hit us is the 14-day quarantine," he said. "That's making everyone cancel."

He remains hopeful that more targeted support is just around the corner for Crawley.

"So many people are set to lose everything they have ever worked for, I don't believe the government could ever or would ever let that happen to so many people," he said.

The number of jobs on offer in Crawley had been rising in recent years

In recent years, the town has enjoyed some of the highest levels of jobs growth and average earnings in the country. It also has among the lowest proportion of adults with no formal qualifications, external. And yet, at Gatwick there is a "concentration of lower-skilled employees," according to a 2014 assessment, external.

Peter Lamb, the leader of Crawley Borough Council, fears the slowdown at Gatwick will have a far-reaching impact on any local business that "relies upon consumer spending".

Without more targeted support for the town - and its major employer - he fears it will end up like parts of the north of England, which experienced long-lasting hardship after the collapse of the coal industry.

"We are talking about a generation of the town's young people having their economic future devastated," he said after Gatwick announced it was laying off a third of its staff in August.

Crawley Food Bank says demand has already more than doubled and it is preparing for it to increase further as furlough ends.

Sharon Golightly, a trustee of the charity that runs the service, is another one of the many people in Crawley drawing parallels between the town's plight and the closure of coalmines.

"When you have a town that is quite highly dependent on one particular profession, it becomes quite disastrous when that comes to a crashing end," she said.

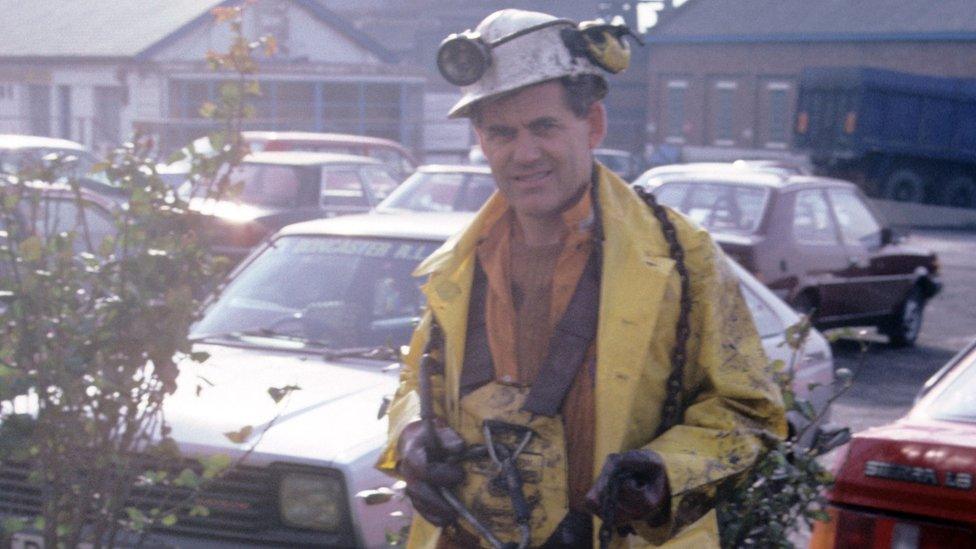

Ex-miner Peter Davies said he sympathised with the people of Crawley

In the Dearne Valley, South Yorkshire, people know only too well how that feels.

At one point 80% of men relied on the area's coalmines for work, until these were closed abruptly in the 1980s. The effects are still being felt today, charities say, external. Crime rates are high, while both life expectancy and educational achievement are below average.

Peter Davies started at the bottom of his hometown pit in Thurnscoe, Barnsley, at 16 and had climbed above ground to work as a manager by the time he was made redundant in his 50s in 1990.

The 78-year-old says he sympathises with the people of Crawley. "I've been through it all and I know what it does, and it isn't easy for the community overall."

In Thurnscoe, South Yorkshire, the local economy has struggled since the mines closed

A parade of derelict shops and homes was demolished and the site left empty

In his town, the hardship was delayed, he said, while people burned through their redundancy pay. But with no jobs to move on to, many were left on the dole, with little to spend in the local economy.

"It knocks on to the whole community when it's a one-industry town like we were.

"Shops shut down, pubs shut down, they're left derelict. It destroys the area."

The Centre for Cities estimates that in Crawley, over half of all jobs are at risk, external due to the town's reliance on aviation, which employs about one in five people.

But, unlike places like Thurnscoe, where poor transport connections contributed to a delayed recovery, Crawley is a 45-minute train ride from London.

And Manor Royal, the vast business park next to the airport, continues to provide employment, despite the loss of some aviation jobs.

Virgin Atlantic quit Gatwick in May

Virgin sold its vast training base in Manor Royal business district near the airport

While Gatwick is a "big part of our economy," comparisons to mining towns are "overstating the point", said executive director Steve Sawyer.

The area has become a "hotbed of innovation, manufacture and design", he said, with jobs in medical technology, pharmaceuticals and logistics companies.

Several firms have moved in recently, and some companies are recruiting, he added.

Gatwick estimates it will take four to five years to recover from the pandemic.

With the right support, it would return to "playing an important role supporting the region's economy, jobs and future prosperity", an airport spokesman said.

Louise Crunden tries to remind herself that she is "just one of the many" out of work

For Ms Crunden, the job hunt has been an "emotional rollercoaster", with low points that left her in floods of tears.

But she's hopeful she'll find work next year - and in the meantime takes some comfort from the fact coronavirus has ended countless careers indiscriminately, irrespective of talent.

"I'm just one of the many," she said. "That's what you have got to say and hopefully at some point it will get back to normal, whatever normal is."

- Published28 August 2020

- Published26 August 2020

- Published19 June 2020

- Published5 May 2020