Showman doctor: From travelling fairgrounds to the Covid frontline

- Published

The A&E doctor's family have travelled with fairgrounds for at least five generations

As a teenager, John Castle lived a double life. He had love and loyalty for his family of travelling showpeople. But at school, in the face of prejudice and discrimination, he felt compelled to hide his roots. Now an NHS doctor, he believes his upbringing prepared him for the pressures of the pandemic.

From his bed inside the caravan, John could hear the thump of fairground music above the whirring diesel generators.

It was not a conventional lullaby, but it had the same effect. "It sent me to sleep and made me feel safe," he recalls.

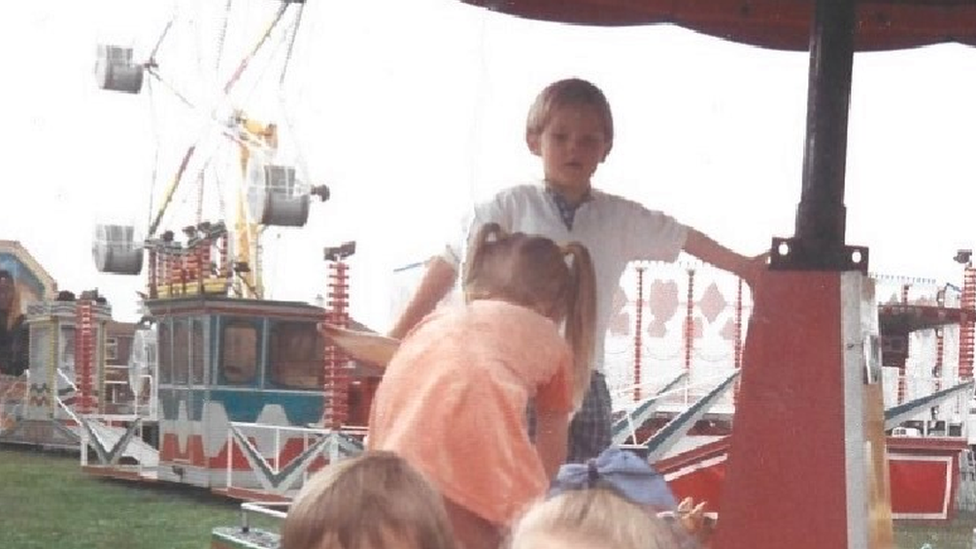

As a young child, he was often on the road and out of school, helping his family run burger vans and rides at fairs across the south coast of England.

Twenty years later, early exposure to this hustle and bustle proved to be invaluable conditioning for life on the Covid frontline at a busy Brighton hospital.

"When I am on the A&E shop floor it feels like I was almost trained to be there," he said. "The multiple noises, the sensory overload, I don't think anything of it.

"That's what I've always known and I thrive in it."

John Castle spent much of his childhood on the road with his family of travelling showmen

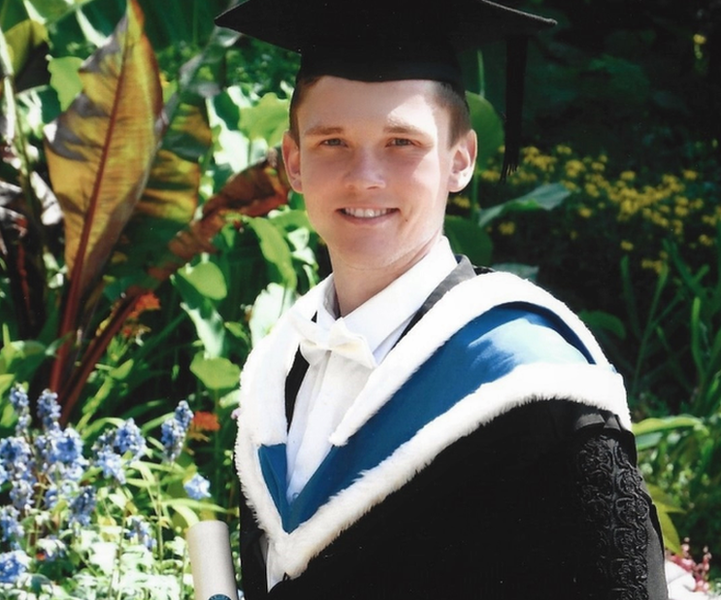

Today, the 28-year-old University of Oxford graduate proudly identifies as both a doctor and a member of the showman community - a centuries-old culture of travelling fairground operators.

"You can be both," he said pointedly, hoping to dispel prejudiced assumptions that, he believes, cast showmen as outsiders, eager to swindle punters and cheat the system.

"We're represented in every field and we have a lot to offer but there are negative stereotypes that really hinder how people progress," he said.

There are more than 20,000 showpeople in the UK, according to the Showmen's Guild of Great Britain, founded under another name in 1889 in the face of attempts to restrict their itinerant way of life.

The community is distinct from Romany gypsies and Irish travellers, but have faced many overlapping prejudices and inequalities, said Vanessa Toulmin, a professor at the University of Sheffield.

About 20,000 showpeople operate travelling fairgrounds across the UK

"They face the prejudice that all traveller communities face, because people assume that travellers don't contribute to the economy of the country, they don't think they are part of the community," said Prof Toulmin, who founded the National Fairground Archive.

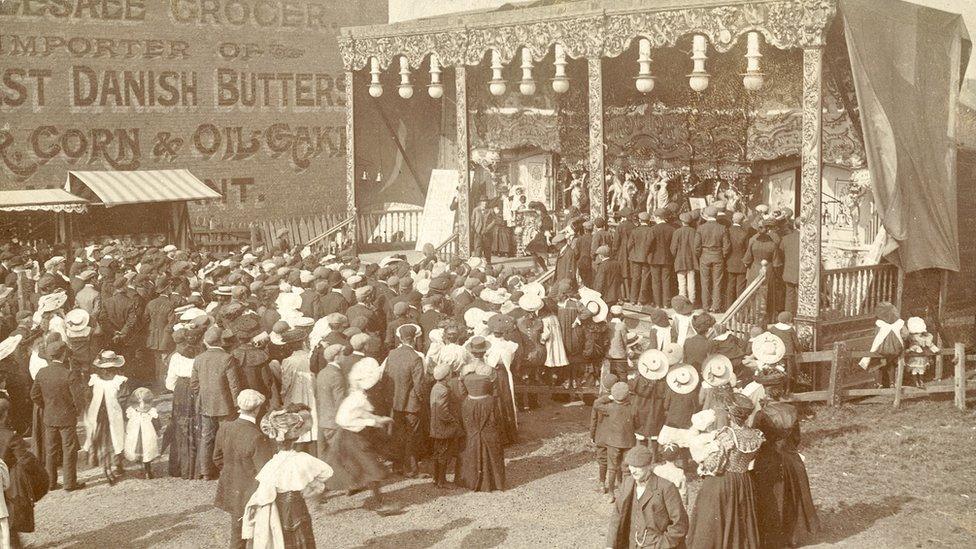

In fact, fairground communities' contributions to British society had been many and varied, with showmen being "early adopters and innovators" in entertainment, including theatre, cinema and holiday camps, she said.

"Cinema went from being a travelling fairground show to an international, corporate organisational structure within ten years," she added. "Suddenly every town had a cinema by 1909."

John's family have travelled with the fairgrounds for at least five generations and "probably longer", he said.

Travelling showmen brought moving pictures to the masses before cinemas opened

Transitioning back and forth between a nomadic life and the more-mainstream society has not always been painless.

Among showmen, from a young age he felt a pressure to be like the other boys; to feign interest in football and engines.

At school in Chichester, West Sussex, when he was not on the road with his family, he felt an equivalent pressure to conform.

He learned to "play a role" and altered his accent, he said.

"It felt like I was living a double life and I had to have two personalities," he said.

"I never felt like I could be who I was at home, who I felt like I was, because people's attitudes changed."

Trying to hide one life from the other was a "huge source of anxiety," he said.

On one occasion, he recalls a friendship ending abruptly after the girl's mother dropped him home to the yard, where his family lived and stored their equipment during the quieter winter months.

"From that point on she never talked to me again, I think because she realised that we're showmen," he said.

John believes an "act of fate" helped secure his place at the University of Oxford

He "retreated into books" and sought solace in schoolwork, embracing a love of nature and science, he said.

Despite missing somewhere between 35 and 50% of conventional schooling, he found a combination of a sharp memory and weeks of cramming guaranteed A-grade exam results.

With GCSEs looming, he began to nurture dreams of studying medicine among Oxford's storied spires.

But once again he felt an equal and opposite pressure from both sides of his life, providing a niggling voice of doubt that drove him on.

"I had this feeling that I needed to prove people wrong," he said.

Founded in the 13th century, Balliol College claims to be the oldest in the English-speaking world

Along the way there were teachers, friends and family - not least his mother - who provided encouragement. There was also, he said, a degree of good luck.

In his final year of secondary school, having got out of bed at 3am to work on a burger van at a weekly market, a conversation with a regular customer would help change the course of his life.

Having shared his dreams for the future, the woman revealed that her daughter was already on the path he hoped to follow.

"Before I knew it, I was meeting her daughter, who put me in touch with a tutor at Balliol College [at the University of Oxford]," he said.

The tutor helped John navigate the "access to education" system - intended to increase diversity - and even put him up while he revised for A-level exams, providing a stable environment for study.

"That was just an act of fate," he said. "I don't know how to explain it."

To John, it is just one example of how his childhood has helped, not hindered, his career.

Working through the pandemic had drawn hospital staff closer together, John said

It instilled an "industriousness" and independent, determined spirit that helped him wade through the course work and the long hours, but it has also prepared him for the stresses and strains, he said.

That resilience has been tested in the pandemic.

One of the toughest moments came when he had to call a patient's son, who was stuck abroad due to travel restrictions, to inform him that his father was "taking his dying breaths", and then hold the phone as he said goodbye.

"You can't leave that behind, you carry that and we will all carry experiences from this with us forever," he said.

The pandemic had left all hospital staff with experiences they will "carry forever", John said

While the past 18 months had at times been "traumatic", it had also drawn colleagues closer together, he said.

The NHS trust, University Hospitals Sussex, had been "very good" at caring for staff welfare, he said.

Despite the pressures, he still feels "privileged" to have chosen a career that allows him to believe every day that he has "made a difference, even in a small way".

"I think that should be everyone's aim in life: to leave the world as a slightly better place," he said.

Follow BBC South East on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to southeasttoday@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published8 May 2020

- Published26 May 2021