What happened to WW2 POW camps?

- Published

Cultybraggan camp is one of only a handful of former POW camps in Great Britain which still has many of its World War Two features

More than 500,000 Italian and German fighters were brought to Britain as prisoners of war during World War Two. They spent the remainder of the war in commandeered stately homes, old Army barracks or hastily thrown together huddles of huts, often built by the prisoners themselves. But what happened to the 1,500 POW camps they called home?

Camp 13, The Hayes, Derbyshire

The Hayes was built in the 1860s by Francis Wright as a wedding present for his son Fitzherbert and during World War One it housed girls from two evacuated London schools

The Hayes, in Derbyshire, was the scene of one of the most famous German escape bids.

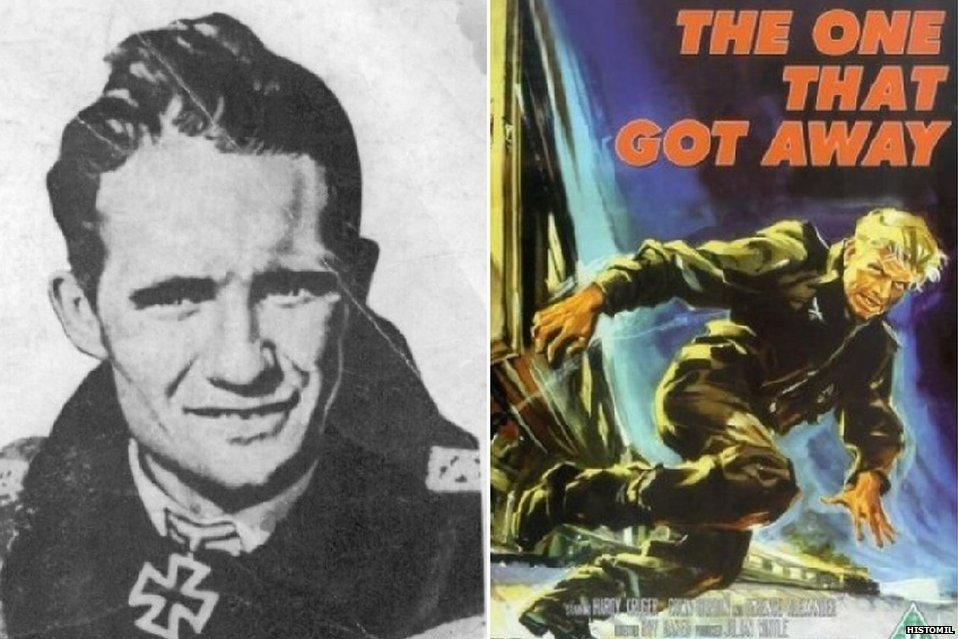

Ace fighter-plane flyer Franz von Werra successfully tunnelled out with four other prisoners, the noise of their efforts masked by a performance of the POW choir.

Posing as a downed Dutch pilot he then managed to get into the cockpit of a Hurricane and was preparing to fly home when he was discovered.

Hayes archivist John Tranter said the entrance to the 50-yard tunnel Von Werra and his co-conspirators dug was only discovered in 1980 behind a fireplace in room 102.

Built as a house in the 1860s, the Hayes in Swanwick became a Christian Conference Centre in 1911, a role to which it reverted after being requisitioned as a POW camp.

Today, it is one of three conference and event centres run by the Christian Conference Trust, a charity which hosts gatherings and meetings for Christian organisations, charities and businesses.

The story of Franz von Werra, who escaped from The Hayes, was brought to the silver screen in the 1957 film The One That Got Away starring Hardy Kruger

Camp 83, Eden Camp, North Yorkshire

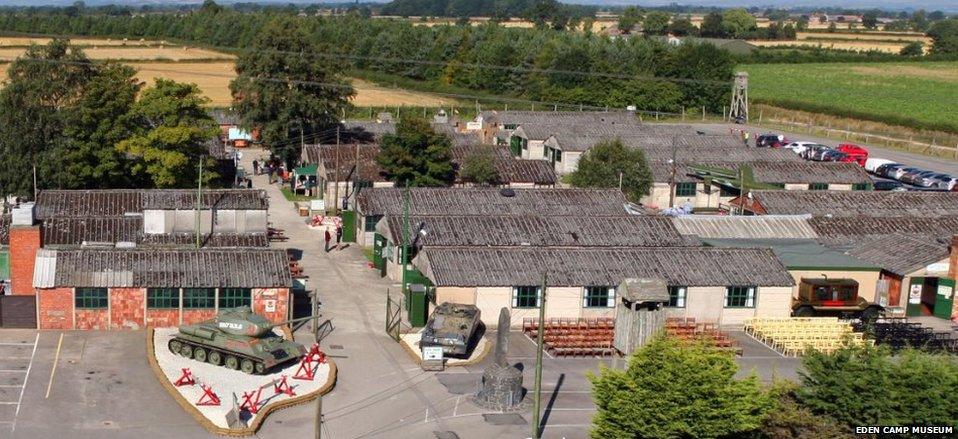

Eden Camp, one of the best preserved prisons, is now a war museum

When the first prisoners were marched through Malton, North Yorkshire, to the newly-assembled Eden Camp in 1942, few would have thought they would be accepted by the community.

After all, these were the enemies the British soldiers had been fighting. But Eden Camp's inmates did integrate, first through work details to help farmers, then by forming bands and holding dances in the town.

The camp is now a war museum and archivist Jonny Pye said prison life was surprisingly pleasant for the low-risk inmates, who were easily identifiable by large red circle patches on the backs of their uniforms.

"They became well-known and a part of the community and came to be seen as people just like us," he said.

Local people developed their own view of the incomers. One noted: "The Italians spent most of their time singing, posing and trying to catch the eye of any female, while the Germans proved more hardworking and reliable than their Latin counterparts."

Eden Camp is one of the best preserved POW camps in the country with its 34 remaining huts attracting 160,000 annual visitors. It is one of only 12 in the UK that still look much as they did during World War Two, according to English Heritage.

After the war, Eden Camp was used to house displaced persons before becoming a home for agricultural labourers and then, in 1955, a grain drying and storage centre.

In 1985 businessman Stan Johnson bought it with a view to turning it into a crisp factory, but a group of Italian former inmates gave him the idea of creating a war museum, external, which opened two years later.

Much of Eden Camp remains, although the old guards' quarters now house an agricultural vehicle business and an electricity substation has been built next door

Camp 21, Cultybraggan, Comrie, Perthshire

More than 100 of Cultybraggan's huts remain

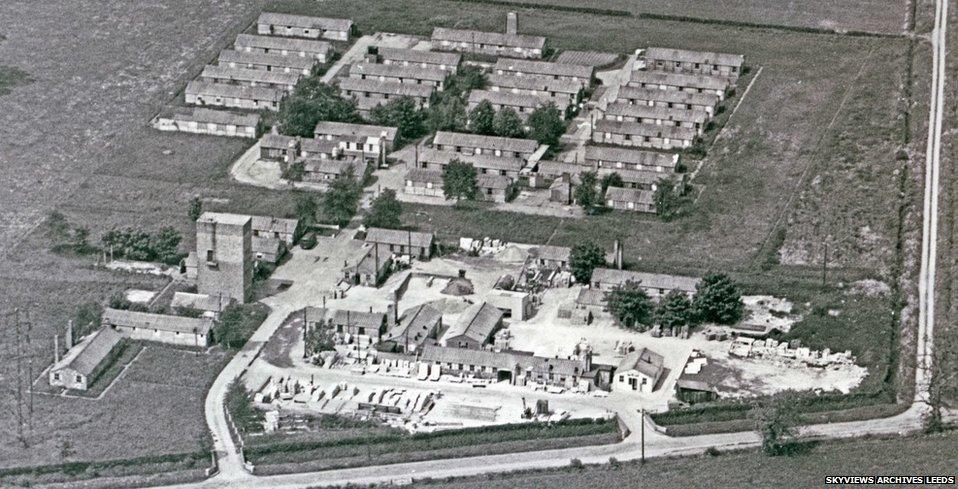

Maximum security Cultybraggan held 4,500 of the most extreme Nazis and was patrolled by Polish guards.

In December 1944 it was the scene of the brutal murder of interpreter Feldwebel Wolfgang Rosterg.

Rosterg had been sent to the camp by mistake and was accused by inmates of exposing a mass escape plan from another camp. He was tortured and beaten before being hanged in Cultybraggan's bathhouse.

Five German soldiers were tried for his murder in London and hanged at HMP Pentonville.

After the war, the camp became an Army training facility and monitoring post, with a bunker built to house the BBC, government ministers, BT and other important groups in the event of an escalation of the Cold War.

In 2007 the camp was taken over by the Comrie Development Trust (CDT) and some of the more than 100 remaining huts have been converted into business units.

Cultybraggan housed the most dedicated Nazis and it is rumoured Rudolf Hess spent a night there

Camp 90, Friday Bridge, Cambridgeshire

After the war Friday Bridge became a camp for agricultural workers, a purpose it is still used for today

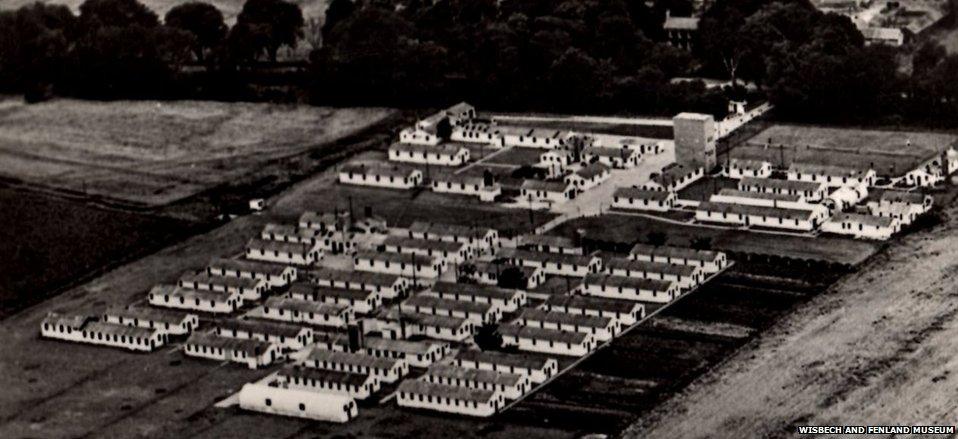

Seventy years after it opened, Friday Bridge is the last camp to still be used for something like its original purpose - although foreign labourers now reside where enemy prisoners would once have been held.

The camp hosted Italians and Ukrainians from 1943 before becoming a hostel for agricultural workers after the war.

Recruitment firm WMS now uses the camp as its base and has built an accommodation block to house 400 European agricultural workers who come to work in Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Cambridgeshire.

Robert Bell, assistant curator at Wisbech and Fenland Museum, said many residents had stories about the camp.

"Many have first-hand experience of it, either by meeting inmates, working at the camp or even being related to prisoners who stayed on after the war."

The museum has several artefacts made by prisoners, including doll shoes made from bread, an articulated snake and a brass ring.

Mr Bell said although they were prisoners, many of the inmates had a great amount of freedom to leave the camp and mingle with the locals.

"It's quite interesting how the prisoners circulated relatively freely about the towns and villages."

The Italian inmates were sent out to work in the fields around Friday Bridge

Camp 93, Harperley, County Durham

Harperley is closed to the public

Though many of Harperley's huts are still standing on a slope overlooking Weardale, the camp's real value lies in the graffiti left there by its inmates.

The camp opened in 1943 to house low-level prisoners, firstly from Italy and - after 1944 - Germany.

"The common view is that the Italian POWs were pleased to be out of the war, but what they wrote on Harperley's walls challenges that," says Roger Thomas, of English Heritage.

Scrawled inside are phrases such as Viva Mussolini, which Mr Thomas said indicated some prisoners were still strongly supportive of the war effort.

The latter inmates painted pictures of the German landscape on the huts' walls.

"Though the buildings at other camps can still be seen they are essentially dumb, they show the camp but don't tell you what life was like for the prisoners," says Mr Thomas.

"Harperley still has the ghosts of its prisoners."

After 1948 the 1,500-capacity camp became a base for displaced persons, many of whom came from Eastern European countries which were now under the sway of the Soviet Union.

However, Harperley has been in private ownership since 2001 and, after a brief spell as a museum and garden centre, is now completely closed to the public.

Two of the 49 huts have been converted into homes for the owner and his family, while Durham County Council has given planning permission for one of the buildings to be used as a cheese factory.

English Heritage said Harperley's value lies in the graffiti left by inmates

- Published31 May 2014

.jpg)

- Published25 May 2011