Josephine Bowes: The forgotten 'pioneer' of the art world

- Published

Josephine Bowes was a keen artist whose ability to find the next big thing was key to the museum's success

More than a century ago, a French actress-turned-aristocrat achieved her dream of building a world class museum in the north of England. But Josephine Bowes's impact on the art world was almost expunged from the history books by her widower's jealous second wife.

For 125 years, the sleepy town of Barnard Castle has been a surprising pit-stop for art aficionados.

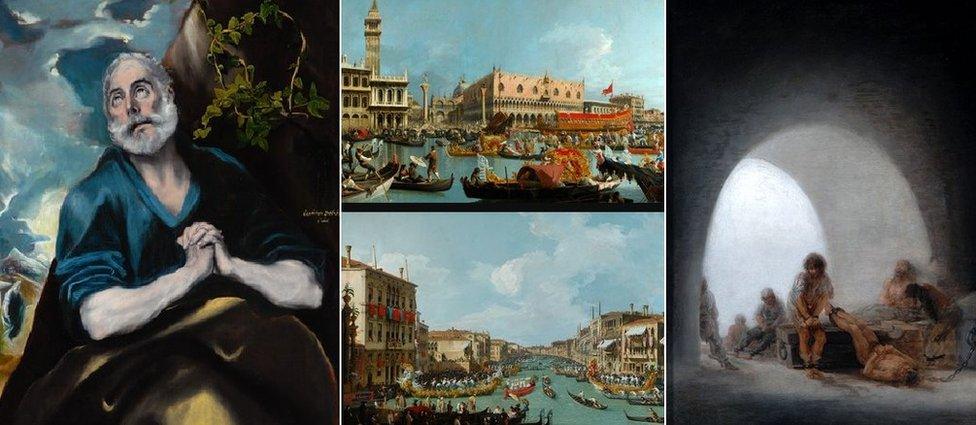

The Bowes Museum, most famous for its silver swan automaton which periodically preens itself from its bed of twisted glass rods and sparkling fish, is filled with fine furniture, paintings by El Greco and Canaletto, and attracts 120,000 visitors a year.

But its beginnings can be traced back to the vision of Josephine Benoite Coffin-Chevalie - a woman described as a "philanthropist" and "pioneer" of the art world, but who at the time of writing does not even have a Wikipedia page, external.

The Bowes Museum is celebrating its 125th anniversary

Her journey from Parisian clockmaker's daughter to wealthy wife of a British aristocrat began in 1847, when she was introduced to John Bowes, the illegitimate son of the 10th Earl of Strathmore and a distant ancestor to the Queen Mother.

He was part of what was known as the demi-monde, a scene in Paris consisting of artists and courtesans, aristocrats and decadence, prostitutes and absinthe drinkers.

To please one of his paramours he purchased the Theatre des Varietes playhouse in the city's second arrondissement - the very place he would first see his future wife - then 22 - take the stage.

John, 14 years her senior, was captivated. And Josephine, like many young Parisian women of her set, was keen to climb the social ladder.

"The way to get power as a woman in Paris was to become the mistress of a powerful man," said Judith Phillips, archivist at the Bowes Museum.

"You would get bought a house and be well looked after and even respected.

"Having a mistress was a common thing, but marrying them was rarely heard of."

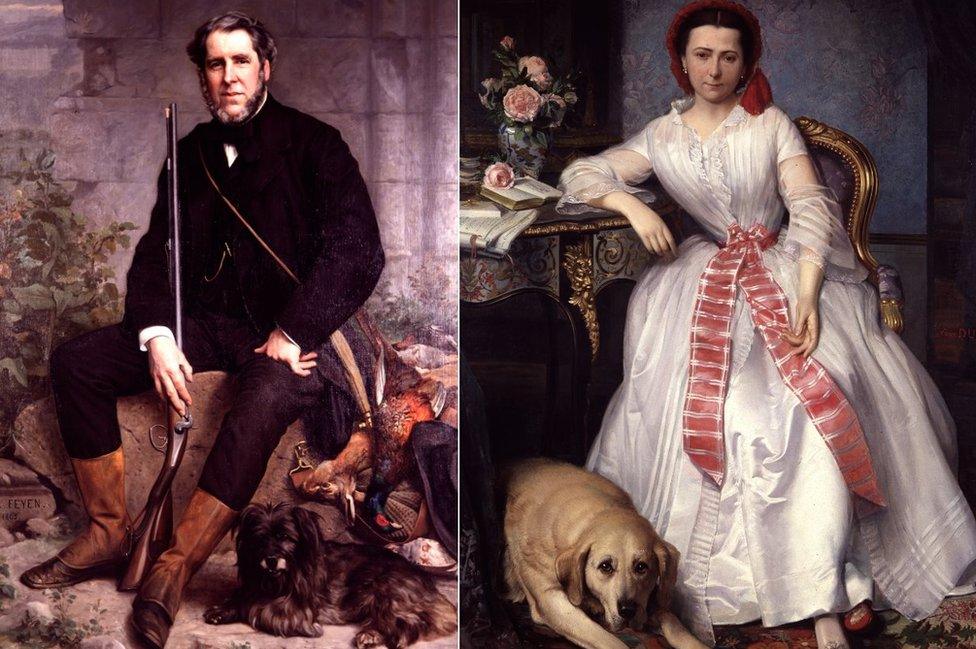

John financed the Bowes Museum while Josephine filled it with works of art

Josephine's allure clearly had an impact on her smitten lover because after a five-year fling, the pair bucked the trend and wed.

As a wedding present, he bought her the extravagant Chateau du Barry near Paris, the former home of a mistress of King Louis XV, which Josephine later went on to immortalise on canvas.

Though they had their home in France, the pair regularly visited John's family estates in County Durham, where the couple decided to leave their legacy - the Bowes Museum.

They had a vision - to improve people's lives through art - and believed that what the farmers and coal-miners of the region needed was a place of cultural refinement.

Because of the John's illegitimate status - his parents having married just 16 hours before his father died - and the stigma attached to not inheriting the title, he was keen to leave a legacy in his own name.

Construction began on the museum in 1869

"They didn't have children and they always knew John's estates would pass back to the family," Ms Phillips said.

"They wanted to leave something behind, but it was more than that.

"They were part of the industrial age, people were becoming better educated and Josephine and John wanted to introduce the people of the area to art and culture.

"At that time art was viewed as a refining agent, exposure to it would just make people better.

"They were philanthropists."

Josephine collected works of artists yet to find popularity such as El Greco, Canaletto and Goya

Josephine was a keen artist and it was her Parisian connections and ability to find the next big thing which was key, Ms Phillips said.

"She knew what was going to be popular before everyone else.

"She had great contacts and knew a lot of the artists when they were young and before they were famous.

"She was buying impressionist-type paintings before Impressionism was even a thing. She was very much a pioneer."

Josephine was also a keen artist and painted the Chateau du Barry, which John had bought her as a wedding present

However, museum curator Joanna Hashagen said Josephine's husband is the more remembered of the two for his contribution to the site.

It is just one of the reasons the museum is marking its 125th anniversary with an exhibition to remind the world of the pivotal role the actress played in its creation.

"Josephine was absolutely crucial," said Ms Hashagen.

"John gets the main billing, he is remembered, but that's not really fair.

"It is fair to say that without his money Josephine would not have been able to do this, but without her he would never have done it either.

"About 90% of the bills and letters from art dealers were addressed to Josephine, she made it happen."

As construction work got under way, there were plans to build an apartment for Josephine to live in at the museum - the assumption being that she would outlive her husband and would spend her widow years organising the collection.

But neither lived to see it.

Josephine Bowes was nicknamed Puss by her husband

Josephine had always suffered from regular bouts of illness and it is believed her conditions included asthma and bronchitis, not to mention more scandalous afflictions rife in their raffish circles.

"We know John had venereal disease," Ms Hashagen said.

"We think Josephine probably had it too, lots of people did, it was a very racy time. That could be why they never had children."

Josephine died on 9 February 1874, five years after she had laid the museum's foundation stone.

She was 48 years old.

But it is because of what John did next that so little is actually known about her.

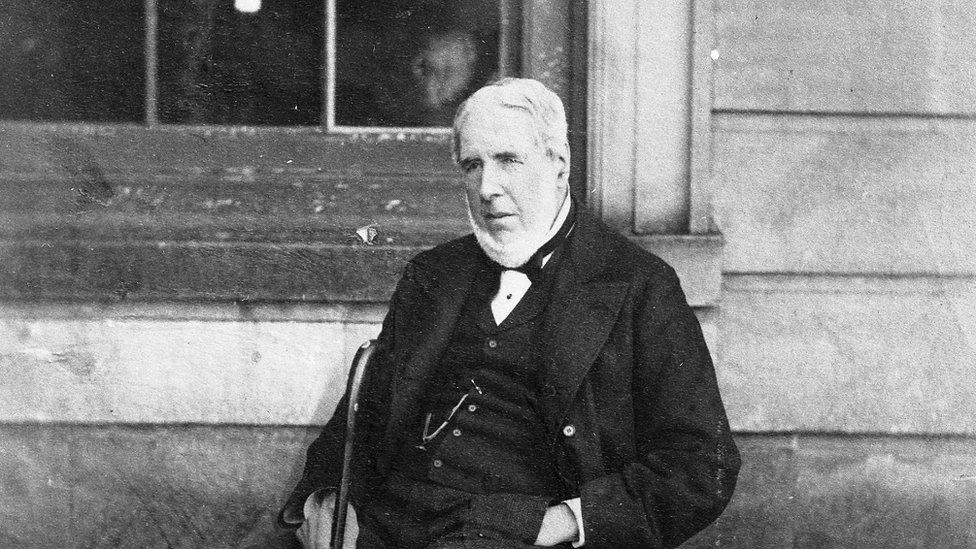

John died at the age of 74, seven years before the Bowes Museum opened

The art collector had amassed more than 15,000 objects for the museum but, thanks to the jealousy of her husband's next wife, few of Josephine's personal possessions actually remain.

Alphonsine de-Saint-Amand launched a ruthless campaign to expunge the memory of her predecessor in new husband's life, for example destroying all but one of the hundreds of letters Josephine had written to her husband.

Realising his error, John was in the process of divorcing her when the stresses of the ill-fated relationship and funding the museum took their toll.

He died on 9 October 1885 aged 74, seven years before the museum opened.

"In fairness to John he was probably lonely and believed his new wife would help complete the museum," Ms Phillips said.

"Sadly that was not the case."

The Bowes' paid £200 for the swan in 1872 - about £80,000 in today's money

The museum opened on 10 June 1892, about 25 years after Josephine laid the foundation stone.

Though she could dispose of Josephine's things, the second Mrs Bowes could do nothing to stop the museum's creation and success.

More than 100 years later, it has cemented its place in the art world as a highly regarded and respected outlet, which in recent years has hosted international exhibitions from Yves Saint Lauren and Vivienne Westwood.

The exhibition pays homage to both Josephine's vision and life, which is far more than the tale of a rich aristocrat being seduced by a racy artist, according to Ms Hashagen.

"When they were apart they wrote to each other every other day and we know from the way John talked about her in letters to other people that he cared for her deeply, he was very thin-skinned and protective of her.

"It is clear they did genuinely love each other," she said.

Josephine Bowes: A Woman of Taste and Influence is on at the Bowes Museum until 16 July. The museum will celebrate its 125th anniversary on 10 June with a day of festivities.

- Published9 April 2017

- Published17 July 2016

- Published12 October 2015