On shift with an NHS surgeon in Middlesbrough

- Published

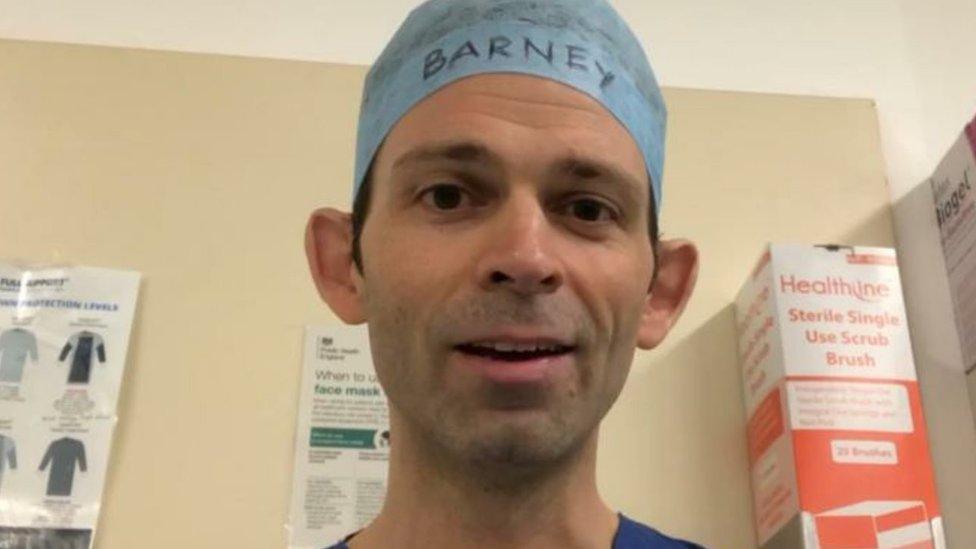

As a vascular surgeon, Barney's job is to operate on arteries, veins and blood vessels

Barney Green describes himself as a plumber, fixing the pipes that carry blood around the human body. I spent four days on duty with the vascular surgeon at the James Cook University Hospital in Middlesbrough, experiencing the hope and humanity as he met and operated upon his patients.

Day One

Jonathan has no kidneys and depends on dialysis to stay alive.

But his life-saving treatment has been repeatedly scuppered by a failed arteriovenous fistula, a blood vessel created in his arm to ease the transfer of blood between his body and the dialysis machine.

In a few hours, Barney will be cutting Jonathan's arm open to install a prosthetic graft which they hope should solve the problem.

Both are in good spirits as Barney and I visit Jonathan's bedside to discuss the surgery, our first job of the day.

"You are always a challenge to me," Barney jokes with Jonathan, but it is clear Barney relishes a challenge.

A tour of patients in intensive care follows, extra gowns and masks needed to prevent the spread of the coronavirus to those recovering after major operations.

Then we head to the operating theatre and I watch as Barney goes to work on an anesthetised Jonathan.

"This will make your toes curl," he warns me as he inserts a sharp pipe into Jonathan's arm.

I'll spare the graphic detail except to say it all goes to plan.

BBC Tees reporter Andy Bell spent four days with Barney Green

It was the only surgery Barney had planned today and he is starting to think about heading home when he gets an emergency call from the University Hospital of North Tees in Stockton.

They have a woman who suffered a dislocated knee in a fall, but they are worried about her artery.

In the space of 10 minutes, Barney abandons his plans for the evening and prepares for surgery.

When Jean arrives her foot is cold and Barney can't feel a pulse in her leg.

A scan shows the artery behind her knee-cap is blocked.

"It would be a hard one to leave and hope for the best. I think we are going to have to explore it," Barney says.

Jean is in a lot of pain and it's distressing to see her suffering.

Barney scrambles to secure a theatre and, for the second time in a day, I watch as he takes up a scalpel.

A part of the artery has been "completely obliterated" and a graft is inserted to plug the hole.

It is intricate work, under real pressure, in what has become a battle to save her leg.

As an uninitiated observer, I'm really not prepared for the final part of the operation.

Jean's leg has been starved of blood and is badly swollen, the solution is to cut her skin from knee to ankle and allow the muscle to bulge out.

"Cut first, ask for forgiveness later," Barney advises.

"I don't know how much that muscle is going to survive, we shall have to wait and see."

While Jean is moved to intensive care to recuperate, Barney heads home.

It is 23:20 and we have been at the hospital for 16 hours, our only sustenance two small slices of chocolate cake, a packet of biscuits and a couple of cups of coffee.

Day Two

"It feels like Groundhog Day," Barney says, as we walk down a hospital corridor together.

I tell Barney I've had about four hours sleep.

"Sounds about right," he replies.

We are on our way to the oncology ward to meet Andrew, a 40-something who has completed Ironman challenges but tragically has terminal cancer.

He has developed a deep-vein thrombosis, a blood clot which could kill him if it reaches his lungs.

Barney wants to remove it so Andrew can have more time with his loved ones.

"It's sobering," Barney later reflects.

"He is younger than me and he's been told without treatment he has three months. How do you make sense of that?

"You've got a family, a job, friends and three months. What are you going to do with it?

"I want to do everything that gives him the best chance of success in everything he wants to do."

Barney operated on Jean after she damaged the artery in her leg in a fall

Back in intensive care with Jean from yesterday, she can now wiggle her foot and Barney can feel a pulse.

He talks her through her operation and explains how he inserted a graft artery section, adding: "You're now worth another £700."

He also tells her about having to cut open her leg to release the pressure from her muscles.

"It might never get back to normal but I want [the leg] to stay attached to you.

"We've quite a long journey still to go, but so far so good."

We head back to the theatre where Andrew is prepped and ready.

"Enjoy the aesthetic," Barney tells him, adding: "When I had anaesthetic the ceiling melted before my eyes."

He removes the clot and another day is done.

Two days in and I am exhausted. All I have been doing is watching.

Day three

Jonathan is in good shape, his arm pain free and dialysis working.

"I'm thrilled by that, I'm buzzing like his fistula," Barney says as we move on through the hospital.

"It's really hard to explain what a sticky wicket Jonathan is on.

"If you haven't got any kidneys you need dialysis, you don't last long with out it.

"To see it working this morning is a huge hurdle we have overcome, now we need to make sure it keeps working."

Our next patient is Robert, and here I learn that surgeons need all of their senses to make a diagnosis.

In an unexpected turn of events, Barney invites me to take a close smell of Robert's foot.

Robert's foot was initially inspected by Barney

"Gangrene," declares Barney. "Once smelt, never forgotten.

"The toe is like a stick of charcoal, we call it mummification.

"You won't eat a Twiglet again after seeing that," is the surgeon's memorable conclusion.

For Robert there is only one option, amputation.

But he seems remarkably calm at the idea of losing his foot.

"I'm happy with that, I'm a realist," he tells me.

"I know if I keep the foot I'm going to have the pain and other things that go with it.

"I don't want to do that. I've got grandchildren, and great grand children, I want to see them. That's my goal."

Barney said amputating Robert's foot was for the best

He is scheduled for surgery the following day, and Barney heads to the staff room for a coffee.

There, I get another dose of hospital reality.

We overhear some other doctors talking about a woman with a badly damaged knee which they fear will need amputating.

They are talking about Jean.

It seems despite Barney's best efforts, she may lose her leg after all because of the damage caused to her knee-cap.

It's a reality of medicine that no matter how much effort you put in, outcomes are not always for the best.

Barney calls another ward to check on another patient only to learn he died during the night.

The James Cook University Hospital has more than 1,000 beds

"I suppose as a family looking in you might say 'oh, they don't care' when someone dies, but we do," Barney says.

"I've been in the same position on the other side of the fence. My mother came in for an operation and didn't survive it."

I tell Barney that I have found it quite sobering, and he agrees, although seems much more matter of fact about it.

"I sometimes think there is something wrong with me, where has my emotion gone?" Barney says.

"Is it normal or abnormal not to feel things all the time. I do have emotions, there are things that get to us but you keep these in check because ultimately what do you want?

"If somebody is having a medical trauma, do you want someone in a flap and dissolving or do you want someone who comes in, sees the job that needs to be done and gets on with it?"

We go to visit Andrew after his surgery.

He seems OK and is enjoying a visit from his friends.

It is clear Barney really cares about his patients and he wants to do everything he can to help, including a little bit of ward burglary when he steals some surgical stockings for Andrew's leg.

It's time to head back into theatre again and I'm sick with nerves, can we save Jean's leg?

The dressing comes off and Barney and the three other consultants seem cheerily optimistic.

More work is needed but it's not as gloomy as the staffroom chatter suggested.

"This looks good, I think that's all you can say right now," Barney says.

Day four

My final day begins with another visit to see Jean.

It's been an emotional rollercoaster following her.

She is getting some tingles in her foot and Barney says it is "hot enough to fry an egg on, which is lovely", meaning there is a good blood flow.

"You look pinker and smilier," Barney tells her, adding: "We are here to serve you, it's the S in NHS."

Our final task is to amputate Robert's foot, so Barney and I head back into theatre.

The hospital has a major trauma unit as well as other wards and services

Barney warns me to brace for a lot blood loss.

"It's the sort of operation you are probably going to think half way through 'oh my goodness what has he done', but actually by the end of it you will think that looks alright now."

A power saw is used to cut through the bone and, after intricate scalpel work, the foot is removed.

I cannot explain how intense it is to watch, but I remind myself Robert needs this so he can get on with his life and be with his family.

"Amputation is not a failure," Barney tells me.

"For Robert this is life giving, in the loss comes the life."

For more, listen to Life in Surgery as part of BBC Sounds series England Unwrapped.

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published15 November 2020

- Published29 April 2020

- Published6 April 2020