Hartlepool by-election: Purple powder and angry dogs in 2004 vote

- Published

Paul Watson told a court he threw purple powder over Jody Dunn in the heat of the moment

By-elections can be riotous affairs and Hartlepool's last one in 2004 was no different. The candidates included an ordained doctor who stayed in a tent, a multilingual karate brown-belt barrister who was attacked at the count and a two-time Eurovision Song Contest entrant.

Hartlepool has been Labour for years. Apart from a month in 2019 when MP Mike Hill was briefly suspended from the party, it has been red since 1964.

But, in 2004, former cabinet minister and key architect of New Labour Peter Mandelson put his comfortable majority up for grabs when he quit as the town's representative to become European Commissioner. No fewer than 14 candidates signed up for the resulting by-election.

One of them was Dick Rodgers, a doctor and ordained priest and the Common Good Party's only candidate. He does not stand in elections to win, he says, but to share ideas. Which is just as well. He's lost in European, parliamentary and local elections in Peterborough, Newark, Henley, Dunfermline and West Fife and the West Midlands, where he lives.

Even busy candidates such as Dick Rodgers cannot come to Hartlepool without fitting in a visit to HMS Trincomalee

Distance from home is clearly not an issue though "Hartlepool is rather a long way away," he says. He rode up on his Honda C90 Cub - he likes motorbikes; "little ones, that are economical" - and pitched his tent on a campsite in Crimdon for the duration of the campaign. "It makes me feel like the SAS, inserting myself into the centre of things, quietly," he says.

He was happy living in a tent - it was warm and cheap - but he found Hartlepool could be challenging. "I think it was difficult to get a rapport, quite honestly," he says. "I found it quite difficult to get through, to really have a heart to heart with people on the doorsteps."

Dr Rodgers spent the campaign living in a tent at a campsite in Crimdon Dene

He also found he couldn't get around all that many houses by himself, and resorted to standing in the town centre with a placard. But he remembers when door-knocking nearly got the better of the Liberal Democrat candidate, Jody Dunn.

She was noted up to this point for her "charisma" and ability to charm even staunch Conservative voters, but the family law barrister was to say something she would come to regret. In her campaign blog - something so innovative back then it was still referred to as a weblog - she described a night of pouring rain and difficult door-knocking.

"We'd picked what appeared at first to be a fairly standard row of houses," she wrote. "As time went on, however, we began to realise that everyone we met was either drunk, flanked by an angry dog or undressed; and in some cases two or more of the above."

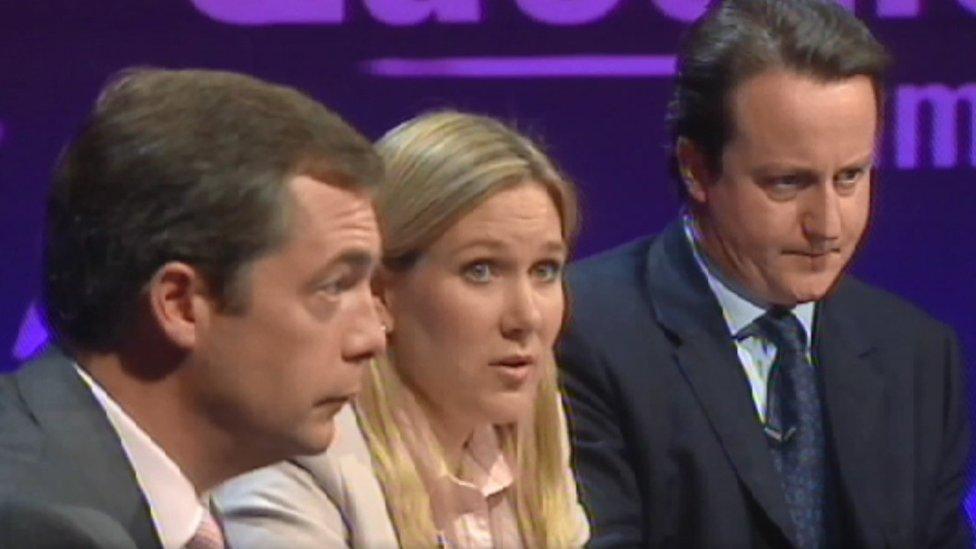

The half Finnish, multilingual Jody Dunn appeared on Question Time, flanked by Nigel Farage and David Cameron

It was a gift for her Labour opponents which, in her words, they "milked". Immediately her tongue-in-cheek description of one street was taken as her opinion of the town's population in general. Labour hired a double-decker bus and followed her around town with it. "As I walked with volunteers they would follow me in the bus with loud speakers repeating the words that I'd said as though I had deliberately insulted people," she says.

She'd meant no disrespect with her "clumsy words", she says, but accepts it was naive not to anticipate the consequences, and that arguing context makes little difference in politics. "I absolutely regret giving them that sort of material but it was never said with any ill intent whatsoever," she says.

'Just cried'

She came so close to winning - reducing Labour's majority from 14,571 to 2,033 - that she clearly has considered the possibility her blog lost her the election. "I don't know whether the result would have been different," she says. But it feels like she does.

The campaign was as dirty as any and her closet was thoroughly searched for skeletons. Some newspapers accused her of being soft on drugs and asked if she had been "involved in some kind of orgy in the back of a van" at a party conference.

"You felt like you were looking over your shoulder the whole time," she says. "It did feel hard. There were times when I came home after a day of doing my best and just cried."

Jody Dunn came close to upsetting a 40-year Labour hold on Hartlepool

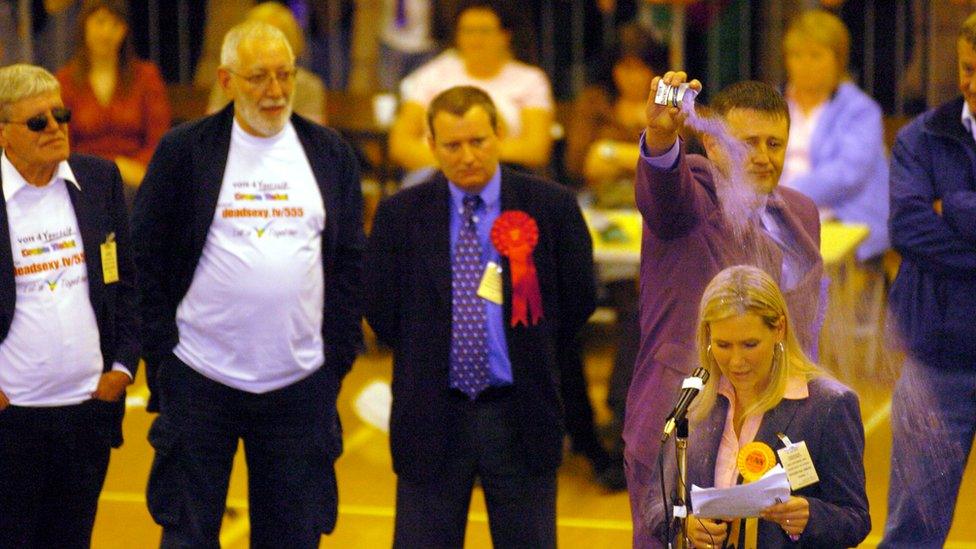

And then, on the night of the count, just as she started thanking her volunteers and the voters who had given her a "really warm welcome", Fathers 4 Justice candidate Paul Watson stepped forward and tipped purple powder, external over her head and shoulders.

"I wasn't sure what had been thrown at me but I knew something had," she says. "I represented something about the country that he hated.

"That made me really sad, that it had to finish on that note and I wasn't really able to say thank you in the way that I'd hoped."

Analysis

By Jonathan Swingler, BBC Look North

This was the first election I covered after finishing my journalism course and my tutors had never covered the scenario of one candidate attacking another. It was surreal to hear shouting and see Paul Watson, who represented Fathers 4 Justice, pour purple powder over the Liberal Democrat candidate Jody Dunn.

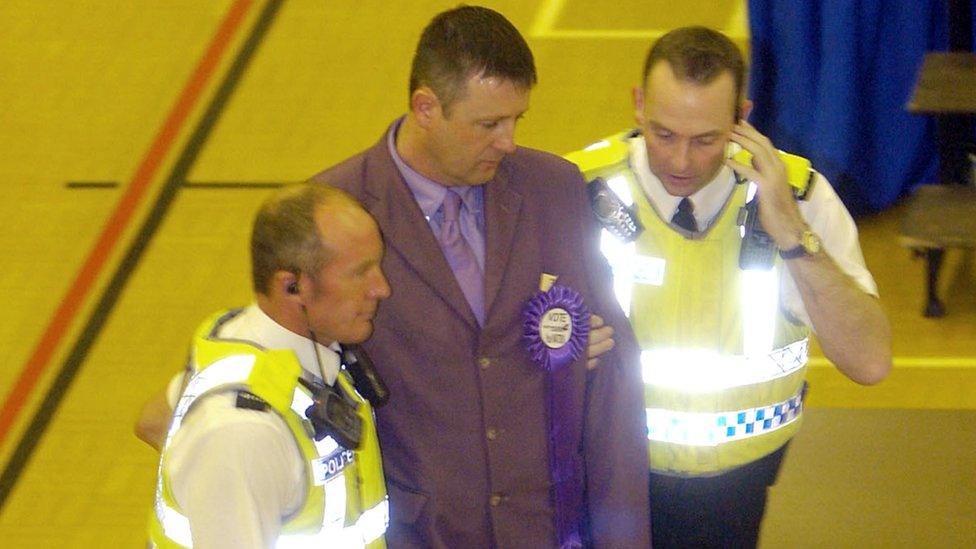

Having seemingly been targeted because of her profession, she carried out her media interviews that night with a smudged purple forehead and told me: "I've had better days." Watson was taken away by police and later pleaded guilty to assault.

I was living in Hartlepool at the time and the town had been turned into a colourful mix of placards as 14 candidates vied for votes. A turnout of just under 46% reflected a general antipathy to their efforts. Labour held on to what had previously been a safe seat but saw their 14,571 majority plummet to just over 2,000.

At the end of the night I asked one of their supporters what he thought. "It was crap," he muttered as he looked at a mic stand covered in purple glitter.

The campaign was more fun for Monster Raving Loony Party leader Alan "Howling Laud" Hope.

"I thoroughly enjoyed it," he says.

He particularly remembers fellow candidate Ronnie Carroll - the only singer to have represented the UK in the Eurovision Song Contest two years running. "We ended up on stage and, when it came to our turn to say something, we both sang Danny Boy," Mr Hope says.

Alan "Howling Laud" Hope alongside Labour's Iain Wright, who won

Impromptu music should not have surprised anyone, given the party's campaign pledge to set up an inquiry to find out "if the Hokey Cokey, external is really what it's all about". That "went down really well", Mr Hope says. Well enough to persuade 80 people in the town to vote for him. He lost his deposit - as usual - but he didn't come last.

Mr Hope met one fan in a town pub who was so supportive he offered transport. "I tell you what, he said, I can get hold of a fire engine - do you want to use it as a campaign bus?".

As a man who once campaigned to incorporate the rules of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? in driving tests, he was clearly never going to turn down an offer like that. For the next few weeks they drove it around town transmitting party slogans via a loud hailer.

Ronnie Carroll represented the UK on successive years at the Eurovision Song Contest in the early 1960s

In the end, Labour came very close to losing.

Jody Dunn polled more votes than any Liberal Democrat before or since - except herself in the following year's general election - knocking the Conservatives into fourth, external place behind UKIP. She had slashed Labour's majority and another 10 days "might have just tipped it", she says.

She believes her party gave up on Hartlepool and moved on, missing the opportunity to capitalise on her gains eight months later. "They'd come in for the by-election and there was a huge presence everywhere," she says. "We only had a handful of volunteers for the general election.

"It just felt to me as though the Liberal Democrats thought 'well, we had our shot, it was a by-election, we had publicity for that, we're not going to get the same, we're just one of many constituencies in the general election, so let's concentrate on our marginals'. I don't think they quite realised that we had made that seat a marginal. It was probably a one-off in history but it was a marginal then."

There are a lot of eyes on Hartlepool again now. Dr Rodgers believes the country needs to pay more attention to the North.

"The North matters and rather cut-off parts of the North, like Hartlepool, do matter," he says.

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.