County Durham beekeeper lifts lid on living the hive life

- Published

George and Susan Soppitt run South Durham Honey

The summer flowers may have wilted away once more but honey bees will still have a lot to do over the winter months. The BBC speaks to a keeper about how he looks after his hives, why he loves these remarkable creatures so much and why every batch of honey should taste a little bit different.

As soon as George Soppitt saw his first beehive, he was all of a buzz.

"They are amazing," the smitten apiarist says, adding: "They are just incredible. Even now, I can still watch them all day."

George's love affair began in 2007 when he was asked to develop a horticulture and wildlife programme at the residential school where he works.

"We got a pond first, then a little while later someone suggested we get a beehive," the lifelong naturalist said.

"As soon as it came, I was hooked, and within three months had a hive of my own."

Each hive is based around a queen and her offspring

Spend half an hour with George at his honey-maker's barn in Spennymoor, County Durham, and it is easy to see why he is so enamoured.

Each hive revolves around a queen that produces up to 2,000 eggs a day which grow to be her workers.

Fertilised eggs become workaholic females, while the unfertilised ones become males, or drones, whose sole function is to mate with the queen.

The newly born females are domestic caretakers responsible for babysitting the larvae, feeding them and the queen, and doing chores such as ejecting dead bees which pose a threat of infection.

After a few weeks caretakers are promoted to foragers, heading out to collect pollen and nectar for honey which they hoard in honeycomb.

George Soppitt now has about 200 hives

They toil 24 hours a day with no sleep or rest, so it is little wonder the average lifespan is about six weeks.

"They literally fly themselves to death," George says with a sadness mixed with respect.

They are also the ultimate survivalists, constantly topping their stores of honey to see them through lean periods, as well as the perfect team players.

"No matter the temperature outside of the hive, inside it has to be 36 degrees," George says.

In warmer months, at the core of the hive is a swarm about the size and shape of a rugby ball.

But in winter the buzzing huddle shrinks to little bigger than a tennis ball, constantly vibrating to generate heat.

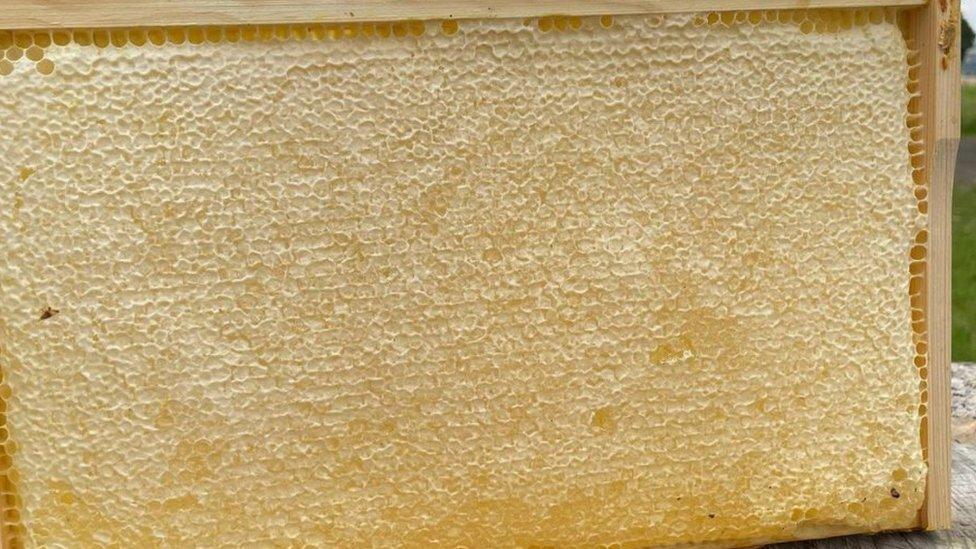

The bees pack honey into cells which they then seal with a wax cap

If it gets too hot outside and the wax caps (which can preserve honey for thousands of years) are at risk of melting, the bees bring water to the hive which they blow with their wings to keep it cool.

They also use their wings as dehumidifiers, blowing air over freshly produced honey to reduce the moisture content and prevent fermenting.

Honey bees are also excellent at responding to environmental changes and correcting human errors, George says.

"As long as you do not kill the queen you can basically do what you want.

"If you mess something up, the bees will fix it. Each one has a job and they just do it. They know what they are doing."

Honey, and you may want to skip this sentence if you are about to eat, is what you get when a bee has eaten and then passed nectar, the bee's interior enzymes "making it special", George says.

He has about 200 hives and in spring and summer they are scattered across County Durham, from farmers' fields to the heather-laden moors, and he also transports a few down to Cambridgeshire to feed on borage.

George's hives are put in fields of flowering crops

Due to the size of his operation he has to put his hives in crop fields - in particular rape seed - where they are welcome guests as the farmers "love the bees" for their efficient pollination.

"I never stop thinking about the bees and where they could feed.

"Every year is different, it's all affected by multiple factors. People ask how much honey I can expect from a hive, the simple answer is I do not know, it is up to the bees."

During winter the hives are distributed on four or five farms and the bees are fed a mix of sugar and water before they start on their honey stores.

Because sugar and water is carbohydrate rather than protein, the bees can ingest plenty of it without needing to go to the toilet which keeps the hives clean, George says.

George is assisted by his wife Susan, despite her allergy to stings, and they sell honey across the region.

One of the farms where George has put his bees is owned by TV presenter Matt Baker

Every batch should taste a bit different, he says, the fluctuations in flavour determined by the flowers the bees feed from.

"The really big producers who you buy in the supermarket blend their honey so it all tastes the same.

"When people buy their honey in the supermarkets they should look on the label to see where it is produced.

"It might say it comes from EU and non-EU countries and that is a bit of a red flag for me.

"We have got very high food standards but non-EU countries can be different and you just do not know what is actually in that honey.

"There are questions about how the bees have been looked after and other animal welfare issues. Have chemicals been used on the fields the bees are feeding on? Have they been given antibiotics? Have they been fed on corn syrup rather than going out to flowers?

"There is a reason a jar of honey could cost 85p, whereas I have to charge £5."

Even if there is snow outside, the bees will keep the core of the hive a toasty 36 degrees

Despite his many thousands of bees, honey-making is a "lonely" business George says, with only about 400 commercial producers in the country.

But he has still been the victim of sabotage, he says, having discovered 50 hives he had placed near an old stately home on the edge of Durham City had been attacked with a poison last Christmas.

"It's jealousy, I think, which is sad," he says, adding: "Taking out our hives means taking us out as a business.

"I'm not interested in owning the whole market, the more honey producers there are means the more bees there are, and that's only good for the environment.

"I do have to be a bit secretive about where my bees are, sadly."

One hive can contain up to 60,000 bees

George has also dabbled with breeding, trying to find top specimens to breed new hives from, although he says he still just learning the craft and science.

So how can you tell if a queen and her workers will be good or not?

"There are multiple signs of good breeding," George says.

These include the amount of honey a hive produces, the cleanliness of the hive, pest levels and the time of day the bees start and finish their foraging (the earlier in the morning and later at night the better).

Then there is the temper.

"Some hives, if you get within 20m they can start stinging you, which is not ideal," George says, having admitted he gets stung multiple times day.

"What you really want is a queen who will let you lift the lid and look down into the hive without needing any protective clothing."

George's next harvest of honey will begin in the spring once the queens have created a new workforce and the flowers are back in bloom.

Until then, though it may be chilly outside, George's hives will still be full of very busy little bees.

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published25 August 2021

- Published5 August 2021

- Published14 June 2021