Newcastle University borehole project strikes hot water

- Published

Geology student Laura Armstrong shows the BBC's Fiona Trott some of the fossil evidence that has been found during the drilling

It is a rare sight. A giant drill, used for projects like the Chilean Miners rescue, dwarfs nearby houses in Newcastle's West End.

Making the city's borehole has been noisy, but after four months, engineers have finally found hot water thousands of metres below the earth's surface.

It is a major breakthrough in their quest to capture geothermal energy.

Scientists say this is the first deep excavation in the UK since the 1980s and one rarely seen in a city centre.

They now want to pump the water back up to the surface so that it can heat local buildings.

It is ambitious and the man behind it says it has kept him awake at night.

Prof Paul Younger, of Newcastle University, said: "It has now cost over £1m, but we're thrilled.

"This hot water could be available 24/7 because it doesn't depend on the weather. It is as cheap and as low carbon as it comes."

'Offshore Bahamas'

Engineers have also unearthed some 300 million-year-old secrets.

Laura Armstrong is one of Newcastle University's geology students who has been examining fossils that were discovered in a block of limestone over 1,000 metres below the ground.

She said: "It is one of the most exciting things we've found.

"These shells and corals suggest that Newcastle was once a tropical environment, like offshore Bahamas."

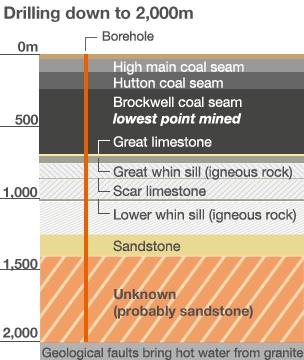

The drill also went through a coal seam at 660m that nobody knew existed.

The historical and geological aspect to this project is something completely new for the drilling company involved.

Its managing director, Tom Pickering, said: "Typically, we work in the gas industry, where the results we're looking for are commercially driven.

"It's the first time we've worked with a university team. It's pretty exciting to take our skills and apply them to a green, geothermal resource."

This work has also captured the imagination of local children.

St Cuthbert's School used to stand on the site of the borehole in the 1920s. Today, year seven pupils are making a film about the project.

George Walker said he had learnt that coal was not a renewable substance, and added: "But back there at the drill, that water's renewable because its come from the core of the earth, where its really, really hot and can be used again and again."

The next step is for scientists to run tests on the sandstone, which acts as an insulator for the hot water.

If there is enough water, they say there is a good chance it could heat the university's new science building and maybe even the local shopping centre.

- Published23 February 2011

- Published23 December 2010

- Published23 June 2010