Easington miners gather during Lady Thatcher's funeral

- Published

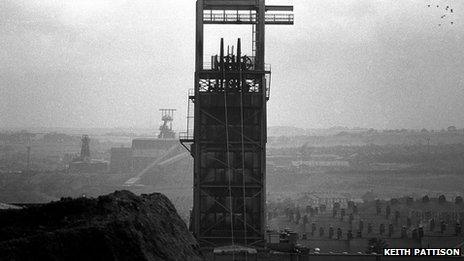

Photographs by Keith Pattison, who documented the 1984-85 miners' strike in Easington Colliery, were shown at the gathering

There are memorial gardens where Easington Colliery once stood.

A mile up in the village former miners and local and national media are skirting round a row.

It was inevitable from the moment it became clear a gathering to remember the 20th anniversary of the pit's closure clashed with Baroness Thatcher's funeral.

In the run-up to the event, someone called it a "party" and suddenly this County Durham pit village had publicity it had not seen since the bitter miners' strike of 1984-85.

Durham Miners' Association chairman Alan Cummings stressed the event had been planned weeks previously and was about reminiscence, not rejoicing.

But the coincidence clearly appealed and he admitted to raising a glass in celebration at the death of Britain's longest serving prime minister of modern times.

"People hated her and what she stood for," he said. "I've got no problem with people saying I'm crass and insensitive."

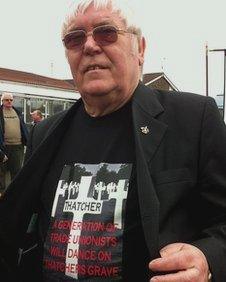

General secretary Dave Hopper was in no doubt he was there to "celebrate Thatcher's death".

"We're here for a party, a good knees-up," he said.

Not the time

As Lady Thatcher's funeral cortege made its way through London, reporters and cameramen gathered outside Easington Colliery Club.

Some guests seemed delighted with the attention, the organisers less so.

A prayer quoted by Lady Thatcher on becoming PM had been rewritten

The function might not have been arranged for the specific purpose of celebrating the former prime minister's death but, to some, the effect was the same.

North East MEP Martin Callanan called it "shameful" and "callous".

Former Conservative candidate for Sedgefield Graham Robb thought the event should have been rescheduled.

"It isn't the time to dance on her grave or to celebrate, whether it be behind closed doors or in public," he said.

"Long after the empties have been collected and the hangovers have worn off Margaret Thatcher's legacy will still be there - and it is a good one."

Outside the community

At the bottom of Seaside Lane the rain blurs the North Sea into the sky.

The coal seams still stretch eight miles under the water but the coastline is no longer black with mining waste.

Easington Colliery closed on 7 May 1993. Grass covers the history.

DMA general secretary Dave Hopper asked: "Do I not look happy?"

Pitmen faced injury, lung disease or death - 83 died in the Easington Pit Disaster of 1951 - and many hoped for something else for their children.

But there is still the feeling Lady Thatcher deprived them of their livelihoods - and for political, rather than economic reasons.

"I'm here to mourn the birth of Maggie Thatcher and to celebrate the end of an era," NUM member Dave Douglass said.

"If people say it's in bad taste to do this, I would say it was in bad taste when miners were killed on the picket lines."

During the 1984-85 strike, miner's daughter Heather Wood worked in the free canteen at the club.

"I think we're celebrating that we're all still here and we're together and, in a way, it's sad because it's 20 years since the pit shut and our communities changed forever," she said.

Lady Thatcher's funeral is a world away for her, "nothing to do with us", unlike the mine deaths in 1951 when "the community stopped, everything stopped".

'Someone's mother'

The club said it would not tolerate inappropriate or disrespectful behaviour at the gathering.

"I can understand the feelings in the area, but we don't rejoice in the death of anybody," club vice-chairman Tom Fenwick said.

The club's concern was so great it was on the verge of cancelling the event, seeking reassurances from Mr Cummings after headlines started showing Easington Colliery in a difficult light.

"At the end of the day, it's someone's mother," Mr Fenwick said.

For Jean Lamb, a miner's wife now living in nearby Hetton-le-Hole, that argument is less persuasive.

"My mother died during the miners' strike and I couldn't even afford a wreath for her," she said.

"It wasn't the miners' fault, it was Margaret Thatcher's because, if the pits had still been open, I would have been able to afford the funeral my mother deserved."

- Published12 April 2013

- Published8 April 2013

- Published8 April 2013