The children who played with asbestos

- Published

Caroline Wilcock used to play near the asbestos factory as a girl

Children in a County Durham village used to spend their days playing with lethal asbestos from a local factory. One, now 51, has cancer. What will happen to the rest?

It is the late 1960s and a little girl is playing hopscotch on a grid she has marked out - not with chalk, but a lump of asbestos.

Forty-five years later she will be contemplating the cancerous mesothelioma in her lungs which is "growing out like a fungus".

"I was doomed from then," Caroline Wilcock says. "There was nothing I could have done between then and now to make a difference. I'm pleased I didn't know it."

She was one of many children in Bowburn who, between 1967 and 1983, played with asbestos from the factory opposite her house.

Its parent company, Cape Intermediate Holdings, external, is paying her a "substantial" out-of-court settlement, although it has denied liability for her illness.

Caroline describes a white, chalky film of asbestos dust on "the grass, the flowers and the bushes". It also settled on window ledges.

The mothers were less impressed. Ann Sproat, a friend of Caroline's sister, remembers them constantly cleaning.

"If cleaning wasn't done we couldn't see out the windows," she says. "It was coming down like little dust particles, like tiny little aniseed balls."

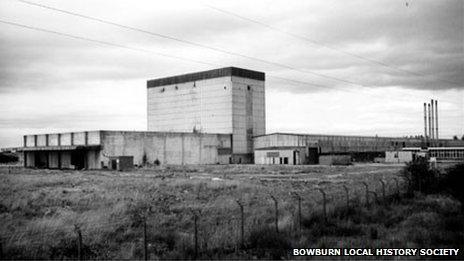

Bowburn's asbestos factory closed in 1990 and was demolished in 1993

The children would share the pieces of asbestos they found, marking out cricket stumps and anything else their imagination conjured up.

The thought of her brother creating a zebra crossing on the main road through the village makes Caroline laugh. It is striking how much she laughs considering the grim nature of the conversation.

She jokes about trying to get on to drugs trials, about the "awful" operation to test a sample of lung and about whether "incapacitated" is the right word for what will eventually happen to her.

Laughing makes her cough. She is also often tired and short of breath. Her treatment is palliative - there is no cure for mesothelioma.

Her doctor, Jeremy Steele, says there must be a factor that makes some people susceptible, but they do not know what it is.

"There's an element of luck - or bad luck - involved," he says.

Although Cape Intermediate Holdings, external will pay her, the company has denied it was responsible for Caroline's illness.

In 1967 the group took over Bowburn's Universal Asbestos Manufacturing Company. Over the years that followed the factory was run by a number of different companies, each a subsidiary of Cape.

Legally, parent companies are not responsible for the liabilities of the firms they own, with certain exceptions which Caroline's lawyers hoped to prove existed in her case.

They maintained Cape was sufficiently involved in the running of the factory and had sufficient knowledge of the risk that it owed a duty of care.

Cape disagreed and "defended the claim on two fronts". Firstly, they did not accept "whoever was responsible for the factory" should have realised the risk posed to people living nearby, her solicitor, Andrew Morgan, explains. Secondly, they did not accept that they were responsible for the factory at all.

But her solicitor maintains "there is no real doubt" that Cape knew asbestos was dangerous and that asbestos in small doses could cause mesothelioma.

"If they had not appreciated that there was some risk of losing then presumably they would never have made any offer," he says.

The company has not responded to repeated requests for comment.

"Cape worked with all the doors open," says Ann. "You could see the men on the machinery and the women. Nothing was secure. It was all stockpiled against the fence and the fence was open.

"This asbestos stuff, that we didn't know what it was then, was never in containers, it was just blowing all over the place. I can remember the men, stacking it up outside but nobody wore protective face masks or anything."

Caroline's solicitor says the company which ran the factory appeared to comply with existing factory legislation but did not consider the risk to the village.

His contention is that Cape should have done, as it was already aware of illness among people living near its asbestos mines in South Africa.

Although Caroline is thought to be the first person to develop mesothelioma "simply from living in Bowburn", her solicitor thinks it is likely some factory employees contracted asbestos-related diseases, and might even have made claims, but kept it private.

"There is also some evidence of increased cancer deaths amongst employees from the factory and amongst their wives who washed their contaminated clothes," he says.

"It is certainly possible that some deaths amongst employees... were not correctly recognised as being related to asbestos exposure."

If people were smokers or former miners the cause was assumed to lie elsewhere, Caroline says.

Another villager, Tina Parry, lost her mother to cancer.

Her father worked at the factory and his wife cleaned his asbestos-covered work clothes, putting them in the washer last because they were so "dusty and dirty" that the kitchen was "full of dust".

"There was no protective wear," Tina says. "He went to work in those clothes and came home in those clothes.

"I remember him coming in the house and the grey footprints on the floor and my mam going mad because she'd just hoovered up."

But her mother also smoked and, when she became ill, it was a while before doctors checked and found asbestos in her lungs.

Tina hopes the support group she is setting up will help people like her father - the ones who feel guilty for surviving, blaming themselves for someone else's death.

It is also for the people worried they might be next, offering clear advice without scaremongering.

"How many of us have got it?" she asks. "I could have it. They said you should go and get screened and I'm thinking, well do I want to?"

Although only about 10-20% of people exposed to asbestos will develop mesothelioma, Caroline's case has left her old village facing an unsettling prospect.

Nobody wants to talk about it. Tina and her father's reluctance to raise the subject with each other, while their own grief was "still so raw", meant they did not realise each was separately involved in Caroline's case.

No longer working, Caroline is contemplating moving back to County Durham so her family can care for her when she cannot look after herself.

She is amused that people who do not know she is ill are envious, asking how she has managed "early retirement" to the countryside.

"I go, 'oh just lucky, I guess," she says, laughing again.

- Published20 November 2013

- Published17 October 2013

- Published7 June 2013

- Published8 November 2012