Secrets and stories of Durham Cathedral

- Published

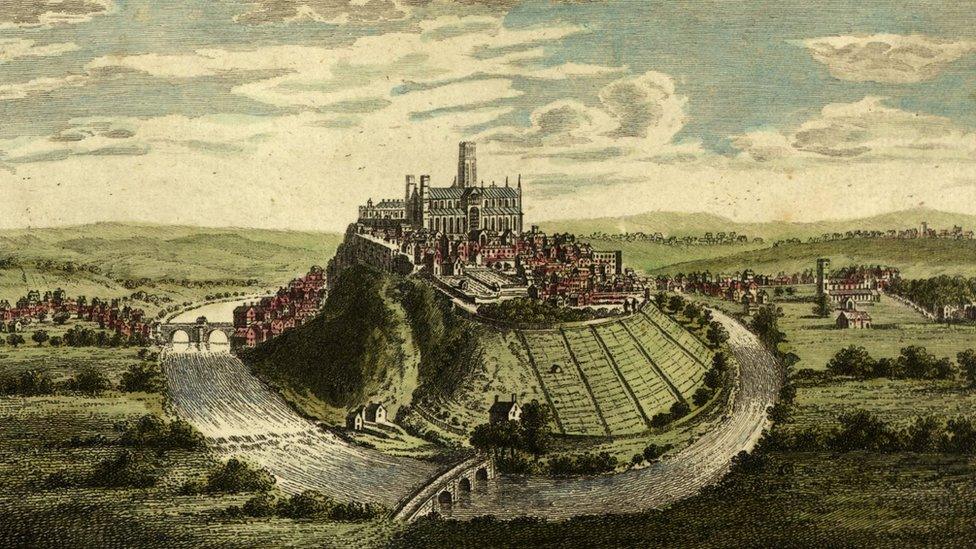

Durham Cathedral was built on top of a hill looped by the River Wear

Durham Cathedral has been voted the country's best heritage site by readers of BBC Countryfile magazine. Here are just some of the secrets and stories to be found in the 920-year-old building.

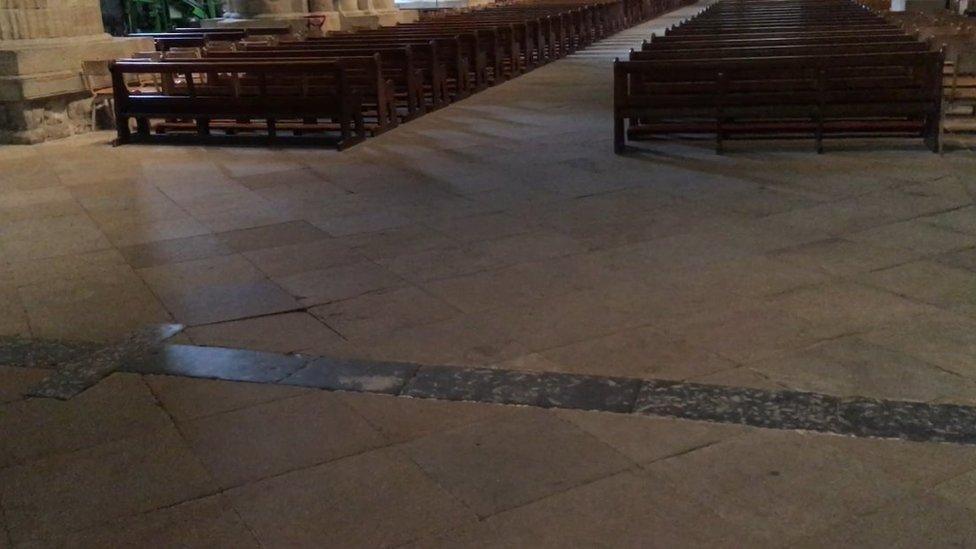

The women's line

A black line at the back of the nave marked the point women could not cross

Today's visitors can be found scattered around Durham Cathedral, speaking in hushed tones, scurrying after spritely guides or just sitting in the pews gazing upwards at the arched ceiling.

But 500 years ago when it was still a Benedictine monastery, half of them would not have been allowed very far into the hallowed hall.

Women were barred from venturing into the nave by a black line across the floor.

"Women were a distraction to the monks," senior steward Malcolm Stabler said.

"Also, it is said St Cuthbert did not like females, and what he said went."

The rule applied to all women, from the lowliest serf to the highest queen.

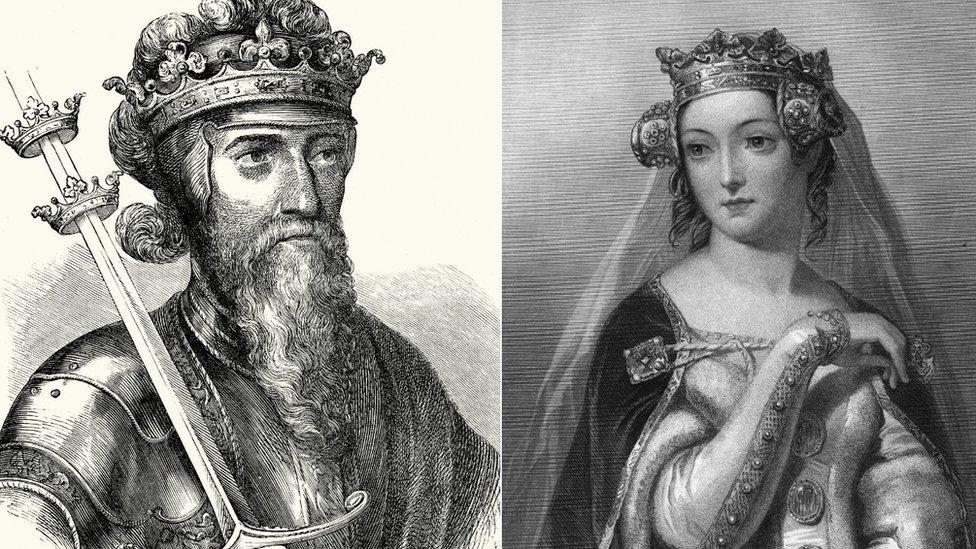

In April 1333, King Edward III and his wife Philippa were staying at Durham Castle across the large green from the cathedral.

One evening, the queen went to find her husband who was praying at the high altar.

King Edward III's wife Philippa got into trouble for crossing the black line while looking for her husband

However, when she crossed the black line the monks asked her to leave.

The king was called and, probably much to the Queen's consternation, sided with the monks.

After 1539 and Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries, the women's line ceased to be enforced.

Apprentice's Column

Secrets and stories of Durham Cathedral

The cathedral's ceiling is supported by rows of giant pillars, as tall as they are around (22ft (6.6m) to be precise), each hollow and decorated with a pattern.

Those closest to the high altar all have a spiral design to swirl the prayers of worshippers up to the heavens.

One pillar, known as the Apprentice's Column, features a near-perfect zig-zag pattern. Near-perfect.

"The story goes the master mason in this section of the monastery in about 1100 went on holiday and left an apprentice in charge," Mr Stabler said.

The Apprentice's Column has a mistake in the pattern

But the apprentice made a mistake, his fault can be found on the fifth ring up where the pattern starts with a "zag".

"The tale of the apprentice's mistake is a wonderful story, if only it were true," Mr Stabler confessed.

"The true reason that mistake is there is because any building glorified to God had to prove that only God was infallible.

"Man was fallible so he had to make a mistake so that was ours, and it's the only one in the cathedral."

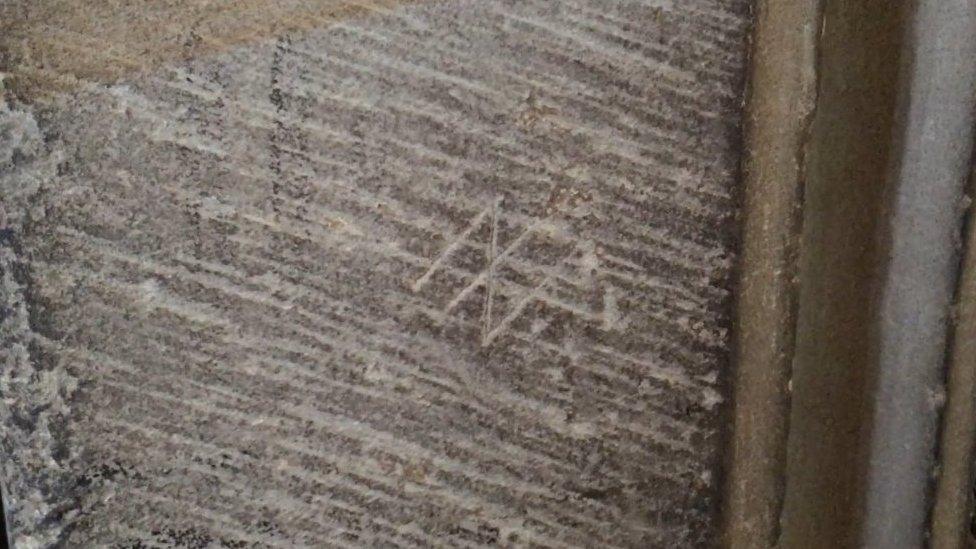

The cathedral is also home to 178 known mason's marks, these being the signatures of the master masons responsible for each section scratched into the stone.

There are 178 masons' marks in Durham Cathedral with many more still to be found, Malcolm Stabler said

Each mason had his own unique mark, and marks of Durham masons have been found at cathedrals around Europe.

"To be able to say you worked on Durham Cathedral was a real boost for the CV," Mr Stabler said.

Missing figures

The Neville Screen has 107 empty plinths

Behind the high altar stands the Neville screen, an enormous carving made from French stone which took a team of workmen almost a year to assemble.

As impressive as it is, it is missing 107 pivotal pieces.

"There are 107 plinths and they are all empty," Mr Stabler said.

"During the dissolution of the monasteries, the monks had three days warning that the king's men were coming to take any valuables.

Senior steward Malcolm Stabler said it is unlikely the missing Neville screen figures will ever be found intact

"The screen held 107 figurines made from white alabaster which were very valuable, so the monks took them down and hid them.

"Unfortunately, no-one knows what happened to them.

"The sad truth is that even had they somehow survived in a crate somewhere, they would instantly turn to dust if the box were opened. They probably are lost forever."

Tombs

Because the cathedral was built as a monument to the revered St Cuthbert, for a long time nobody else was allowed to be buried there.

But in the 14th Century the rules were relaxed for the Neville family of Raby Castle in Staindrop, 19 miles south-west of Durham.

The Nevilles were great benefactors of the cathedral and donated the Neville screen.

The tomb of Ralph Neville is surrounded by figures known as weepers, said by some to represent Ralph's 19 children.

All are facing outwards apart from one.

The weeper on the left is facing a different way to the others on Ralph Neville's tomb

"Ralph had one son he really didn't like," Mr Stabler said.

"Before he died he gave orders that the figurine of the family's black sheep face the wrong way.

"It's a nice little story but in truth it might be the figure is the family's vicar in prayer for the departed Ralph."

One other tomb of note is the ornate affair of Bishop Hatfield.

Bishop Hatfield's tomb features the face and crest of King Edward III

"The bishop was great friends with King Edward III and the pair had fought together at the Battle of Crecy in 1346," Mr Stabler said.

"He asked the king if he could use the king's coat of arms and a depiction of the royal face on his tomb, eventually the king agreed.

"Bishop Hatfield's tomb is the only non-royal tomb that has a royal likeness and coat of arms on it."

The clock

Durham Cathedral's clock was untouched by the Scottish soldiers held there after being captured at Dunbar

Between September 1650 and March 1651, Durham Cathedral became a prison for 2,500 Scots defeated by Oliver Cromwell's forces at Dunbar.

The prisoners, whose ultimate fate was to be sent to America as slaves, were told they could burn anything wooden inside the cathedral to keep themselves warm.

But no matter how cold they were, they never touched the large wooden clock standing in the southern side of the main transept near the Apprentice's Column.

"Engraved on to the clock is a thistle, the national symbol of Scotland, which the soldiers respected too much to destroy," Mr Stabler said.

"It's a nice story, but the truth is if you were locked in here day and night, why would you destroy the one thing that kept you in touch with the time and date?"

Bishop's Throne

The Bishop's throne in Durham Cathedral is the highest in Christendom

For a cathedral to be a cathedral, it must have a cathedra, a bishop's throne.

And Durham's is bigger than the rest.

"One morning Bishop Hatfield asked some of his monks to go to the Vatican and measure the height of the Pope's throne," Mr Stabler said.

"When they came back he told them to make his throne one inch higher as he wanted the highest throne in Christendom.

"Durham's is still the highest throne in Christendom.

"You learn something new every day here."