Last coal shipment leaves River Tyne

- Published

The 12,000-tonne load will leave the Port of Tyne for Belgium on a vessel named Longwave

What is thought to be the last shipment of coal from the North East of England has left the River Tyne. Extracted in County Durham, the 12,000-tonne load, bound for Belgium, raises questions for those who once worked deep down the pits, and for the next generation looking to a cleaner future.

The fact that coal was still being exported from the Tyne came as something of a surprise to former colliery mechanic Billy Middleton.

Now aged 79, he started work when he was 15 at County Durham's Wheatley Hill Colliery, before moving on to Thornley and then nearby Easington.

"I'm more shocked than anything, I didn't even know," the former blacksmith said.

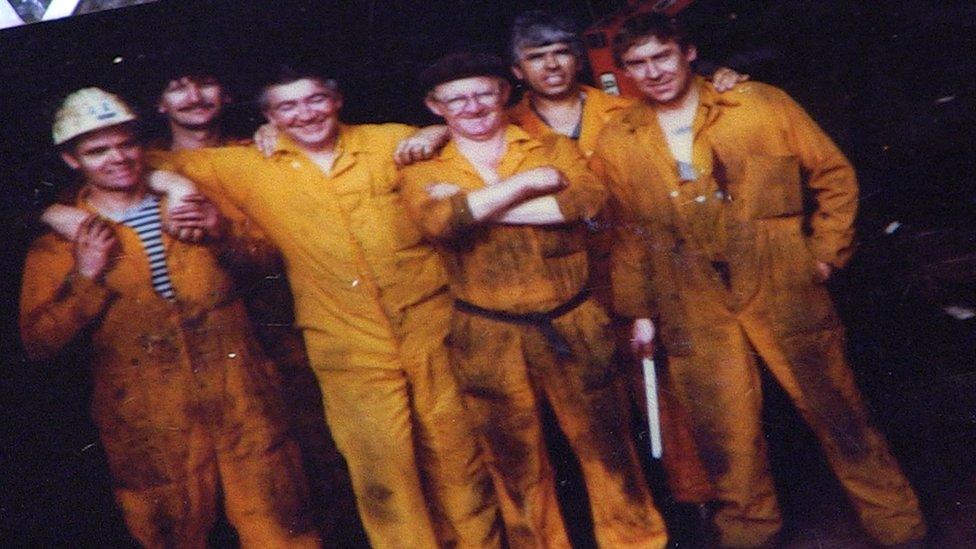

Billy Middleton (far right) and his colleagues at Easington Colliery

"All of our collieries closed, a lot of men took it badly. If they find out there's coal coming from the Durham coalfields going to Belgium, they won't be happy with that.

"As far as I'm concerned 1994 was the end of it all. It was an end of an era, as simple as that."

Billy keeps his heritage alive at Durham Mining Museum, external, based at Spennymoor Town Hall. It features an online archive of its coal mining past and he was interviewed about his work for a documentary., external

Billy in 2019 during the recording of a documentary about coal mining, recorded by Lonely Tower

"My fondest memory?" he chuckled. "I loved every minute of it, there was something different every day.

"When I was in the shaft you only worked six-hour shifts, it was a dangerous job, it was a cold, dirty job.

"It was a pleasure to go to work, all the lads used to get together and the camaraderie was fantastic."

'Everyone hated Thatcher'

The year 1993 signalled the end for County Durham's collieries. In 2005, Ellington Colliery, in Northumberland, was the last to close in the North East.

However coal has continued to be extracted from open cast mines, albeit on a much smaller scale.

This last shipment came from Fieldhouse, near Rainton Meadows, where 500,000 tonnes of coal has been mined between 2018 and 2020 by Durham-based Hargreaves (UK) Services. It now wants to move into low-carbon fuel.

"I was proud as punch that I was a mechanic at the collieries, I would never have packed it in, I would have been there until I was 65 but unfortunately when the collieries closed, I had to pack it in just like everybody else," Billy said.

Striking Durham miners outside the iron gates of the Miners' Hall at Redhills on 19 February, 1981

He remembers the strikes of the 1980s, and even the mention of the name Margaret Thatcher is still very raw.

"Everyone helped each other, at the end of the day we got through it, it was tough for us but we got through it," he said.

"She [Thatcher] was hysterical, she was absolutely disgraceful. When you saw what was happening in Yorkshire, that was absolutely awful.

"I remember when she died, there was a do on at Easington, everyone thought it was just like a centenary day but it wasn't. Everyone hated that woman for what she did."

Billy left Easington Colliery before it closed in 1993. He was 46 years old.

Still living in the former pit village of Thornley, he remembered how clean the area became.

"We have a lot of green belts now, there's no smoke, no muck flying about, you could put your washing on the line, no more arthritis," he said.

"A lot of people said it was a good thing when the pits closed but at the end of the day, this was our heritage.

"We get all the children in from the schools to the museum and they don't even know what a piece of coal looks like."

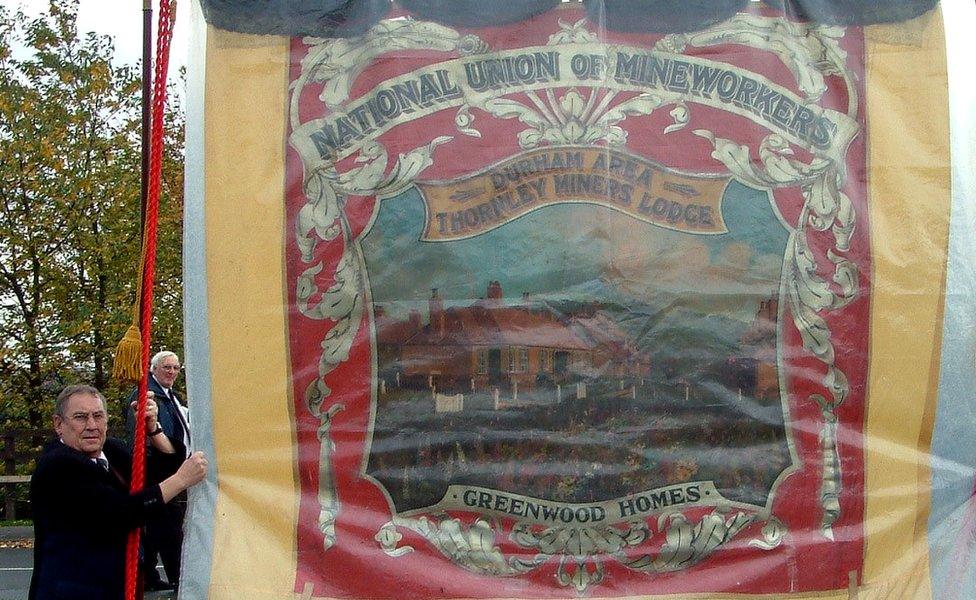

Billy pictured in 2005 with a banner of his former colliery

For student Abel Harvie-Clark, from Newcastle, the last shipment leaving the North East offers a chance for change.

"I guess it is symbolic, I guess I'm happy it's the last one," the 19-year-old said.

"I'm not happy that it's still going, I wish the last one was the one before it and the one before that."

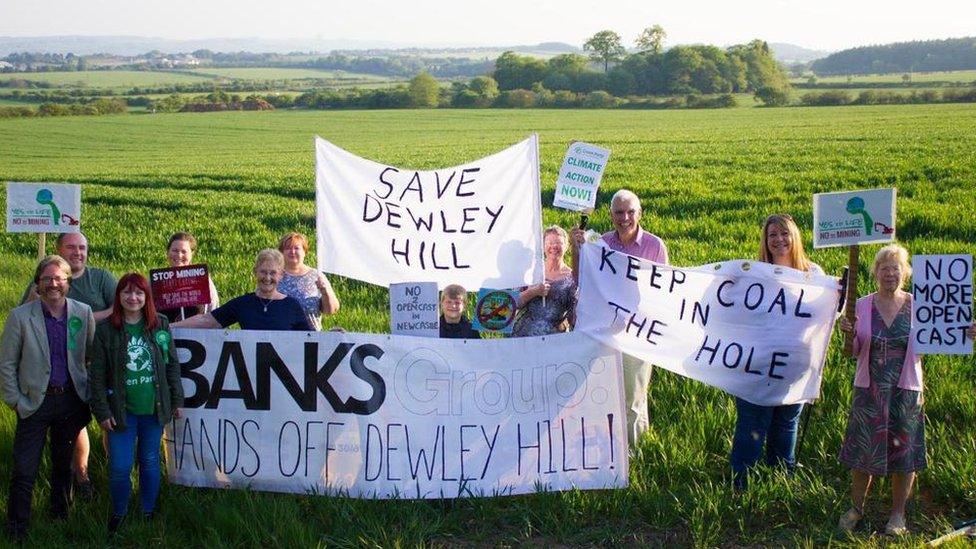

Abel joined other young campaigners in a bid to stop a mine from opening

Last year Abel, who is also a member of the UK Student Climate Network, joined a campaign against plans for an opencast coal mine on greenbelt land at Dewley Hill, near Throckley in Newcastle.

It was rejected by the city council in December as not being "environmentally acceptable". Durham-based The Banks Group, which said it would create jobs, is still considering whether to appeal.

"People are still digging up coal which seems crazy because we are aware of how damaging it is," Abel said.

"They are living in a world where climate change isn't a thing."

Abel wants firms to move into greener energy

Abel said that while jobs were important, it was "a sad situation" where those being offered were "so polluting and dangerous for the whole world".

He highlighted how offshore wind farms could bring "huge opportunities" in terms of "good employment" to the North East, as well as energy.

"Even though people often reply to that saying we need coal to make steel that's not true, there are ways of making steel without coal, using hydrogen for example," he said.

"People are proud of their mining history but people in the North East do want to be part of new technology, not the old ones."

He has discussed the region's coal mining past with his fellow campaigners, saying: "We are totally proud of the North East's history with coal, but also we don't want to glorify that in a way in which people sort of idolise it and romanticise it, I don't think that's at all part of it. It wasn't easy.

"The proudest thing about the history of mining is probably the miners' strikes and the communities that built up around it, rather than the coal itself.

"I think we are quite happy to keep it in the past really, there are much better industries, especially green industry, that we would much rather embrace in the future."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published8 December 2022

- Published17 August 2020

- Published18 December 2020

- Published26 February 2020