Meadow Well: Is the stigma unfair 30 years after riots?

- Published

Whatever the root cause of the Meadow Well riots on the night of 9 September 1991 they have dogged the estate ever since. Is the picture people still have of this North Tyneside community 30 years later fair?

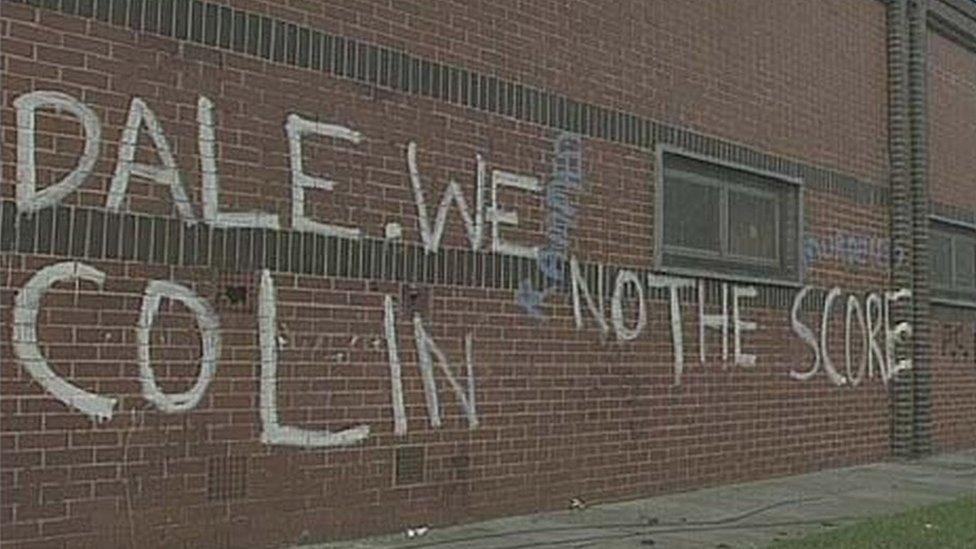

The match that lit Meadow Well's tinder box - literally - was the deaths of two joyriders, 17-year-old Dale Robson and Colin Atkins, 21, who crashed a stolen car while being followed by police.

Rumours were officers had forced them off the road, although Northumbria Police quickly clarified they had been half a mile behind.

It did not matter. For a community already suspicious of police - and believing the animosity to be mutual - the damage was done. Tensions bubbled and, three days later, years of poverty, neglect, unemployment, soaring crime and the stigma of being a problem estate came to a head.

Hundreds of young people went on the rampage, looting and setting fire to shops, cars and buildings.

The joyriders' deaths were the catalyst for unrest that was already brewing

An electricity substation was burned out, leaving the whole estate in darkness all night, lit only by petrol bombs and burning buildings.

Resident James Mason said it was "going to happen sooner or later".

"Everybody just gathered round and it just sort of kicked off," he said. "Petrol bombed the youth club, took the telegraph poles down for road blocks."

There was "smashing, torching, looting" and some shops with their shutters down were ram-raided, he said.

Another resident who saw what happened - Stephen Bainbridge - described it as "horrible". "You could hear them all shouting and bawling and that and throwing bottles and bricks and everything," he said.

James Mason remembers "mayhem, fires, a lot of youths"

Riot police arrived and cordoned off the estate to stop people going in and out but did not attempt to regain control or make arrests until 02:00, about five hours later.

"There would have been bloodshed, there would have been a lot of bloodshed, if the police had tried to break it up," Mr Mason said.

"They wouldn't have stopped it. They couldn't have."

Former Northumbria Police officer Bob Crilly remembers how earlier in the day youths had thrown a piece of concrete at a police van, smashing the wing mirror. The officers in the van thought "we've got criminal damage, a bit of a disorder, let's lock them up", he said.

"Unfortunately the van commander decided the damage to the police vehicle was more important so we tear away in the van back to the nick," Mr Crilly said.

"I'm thinking, 'hang on, this is us running away'. I'll still say to this day that that started the riot."

Riot police cordoned off the estate during the riots to stop people going in and out

Buildings were petrol bombed and shops looted during the riots

In the days that followed, Margaret Nolan, who still lives on the estate, became the unofficial voice of the community, answering questions from the influx of reporters.

"Prior to 1991, many of these houses were boarded up and people wanted to move all the time, even if it was to the next street," she said. "They just wanted to get out.

"We had been pleading with everyone to give us some help because cars were going and crime was up and people were very worried and very afraid."

Speaking to a BBC documentary crew in 2012 another resident, Carole Bell, said they had become a "forgotten people".

"If you tried to report crime you were ignored, if you wanted repairs done on your housing you were ignored, if you'd seen a fire you were ignored," she said.

"It was just like nobody bothered anymore because it was a waste of time."

The estate in 1991 had soaring rates of crime

Residents said they had been keen to move out of the estate

But, after the riots, millions of pounds were spent on the estate. Old houses were demolished or refurbished and new ones built. Road layouts and home boundaries were rearranged to deter criminals and give people a sense of ownership.

A new community centre and health centre were built. CCTV was installed and community police officers were put on the streets to bridge the divide between sceptical residents and the distant police force.

But parts of the Meadow Well, home to about 6,000 people, are still among the most deprived in the UK. Life expectancy is 10 years shorter than in Tynemouth, just a mile-and-a-half away, and crime is still a problem.

Residents say there are drugs on the estate, which brings violence and "regular" burnt out cars. Children have nothing to do and the boredom leads to mischief, they say.

But organisations like Meadow Well Connected, the Cedarwood Trust and Phoenix Detached Youth Project, say vast improvements have been made and it is unfair the estate remains tarnished by its history.

Sarah McDonald has lived on the Meadow Well for almost 20 years

Sarah McDonald, who works at Meadow Well Connected community centre, said she had been "so nervous" about coming to live on the estate but it had been "the best move I ever made".

"Everybody is so friendly," she said. "I couldn't be happier."

Resident Jamie Marsh also speaks warmly of a community where "everyone is protective of everyone".

"As much as it gets slated, it's nothing like what it was years ago," she said.

Her husband John Marsh accepts "you still get your idiots now and then - but I think you get that anywhere".

Ms McDonald says outsiders judge the estate by its history and miss the "good things in people".

This uneasy coexistence of good and bad was something experienced by former BBC Radio Newcastle reporter Barbara Henderson, who was sent to cover the riots. She was attacked, but then taken in to someone's home and given a cup of tea.

Recalling events 15 years later she said: "Given the intimidating atmosphere on the estate that night, it seemed overwhelming that some people were still able to demonstrate a basic human kindness.

"I've been able to walk around the estate since and discover, of course, that most people are like this - and the violence that happened was a terrible aberration."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.