RNLI Cullercoats' Geoff Cowan celebrates 50 years

- Published

Geoff Cowan has spent 50 years saving stricken sailors and swimmers from the turbulent North Sea. He shared his memories with the BBC.

A two-year-old boy stands next to a lifeguard boat, his mother captures the moment in a black and white photograph.

Decades later, he is beaming proudly at the camera, a British Empire Medal pinned to his chest in recognition of his years of saving lives at sea for the RNLI.

"I guess it was inevitable I'd be on the lifeboat," Geoff says with a laugh, as he shows off his mum's old picture.

Geoff was pictured with a lifeguard boat when he was two...

...and got a British Empire Medal for his RNLI service in 2020

He grew up in Cullercoats on the north-east coast and enjoyed a childhood of "messing about with boats".

Geoff was 14 or 15 when he helped with his first RNLI rescue - too young to officially enrol but not to get stuck in.

"I was with my boat on the beach and saw the lifeboat station doors open, so went to have a look," Geoff recalls, from the comfort of one of the large sofas in the crew's lounge.

There was one man on duty when the call came in, bearing the news that two canoeists had capsized beyond the harbour wall.

"It was just me and this guy, and he said 'give us a hand' - so I did," Geoff recalls.

Cullercoats is on the north-east coast, between Tynemouth and Whitley Bay

After that successful rescue he was always going to become an official part of the crew, enlisting in 1973 after he turned 16.

"It was a natural thing for me to do," Geoff says, adding: "It was a chance to be around boats and help people.

"These lifeboat volunteers were looked up to as heroes."

He continued volunteering alongside his day job as a marine engineer officer in the Merchant Navy, and later, running his own company specialising in power generation.

He spent 15 years on Cullercoats' inshore boat, before being headhunted by nearby Tynemouth to be a mechanic and deputy coxswain on their larger Arun class, all-weather craft.

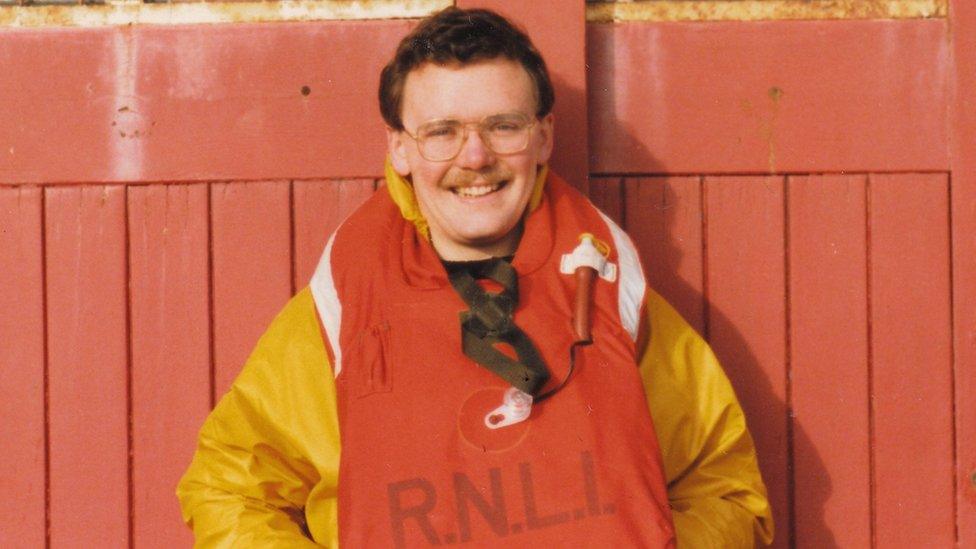

Geoff (pictured in 1990) has been a part of both the Cullercoats and Tynemouth crews

After retiring from going out on rescues in 2002, he returned to Cullercoats to take up the role of water safety officer.

Over that time he has seen huge changes in the training and technology, as well as the types of call-outs.

The vast majority used to be to stricken fishing vessels, but now it is almost all leisure-based call-outs, such as swimmers, paddleboarders and kayakers, as well as a worrying rise in so-called "despondent persons".

A lot of the jobs were "mundane", he says, involving the towing of broken-down boats.

Geoff (pictured in 1994) cannot remember how many call-outs he has taken part in

But some do stick in the memory, for both good and terrible reasons.

In 1999, a yacht on a corporate away-day pitch-poled as it returned to the Tyne from a North Sea swelled by big easterly winds.

Three people were hurled into the frothing waters, one having been smashed through the yacht's windshield.

Geoff had seen it heading seaward earlier and wondered if he might get a call about it. He was part of the crew that hauled the trio who fell overboard out of the river but, despite CPR efforts, two of them died.

"It's a sad fact of life, but at the end of the day not every rescue is going to be successful, "Geoff says.

"In your own mind you do look back and think 'is there anything I could have done better'? Could I have got there quicker, done a better job of the CPR?'," he adds.

"We have got to say we did our best, and what more could we have done?"

Geoff has been teaching water safety since 2002

As a water safety officer, Geoff's role is to make people as aware as possible of the dangers of the sea and how best to mitigate them.

He can remember a lot of "daft and stupid" things with a mixture of humour and frustration.

Like a couple paddle-boarding at Tynemouth with their 18-month-old child a year or two ago.

The man had fallen in the water and was unable to get back on his board, the woman was shouting at the lifeboat crew to get their child who was not wearing buoyancy aid.

Or there was the boat owner who went out three weekends in a row and on each occasion suffered engine failure and had to be towed back in.

"We talk about safety at sea but is there actually such a thing?," Geoff says, alluding to the inherent dangers of open waters.

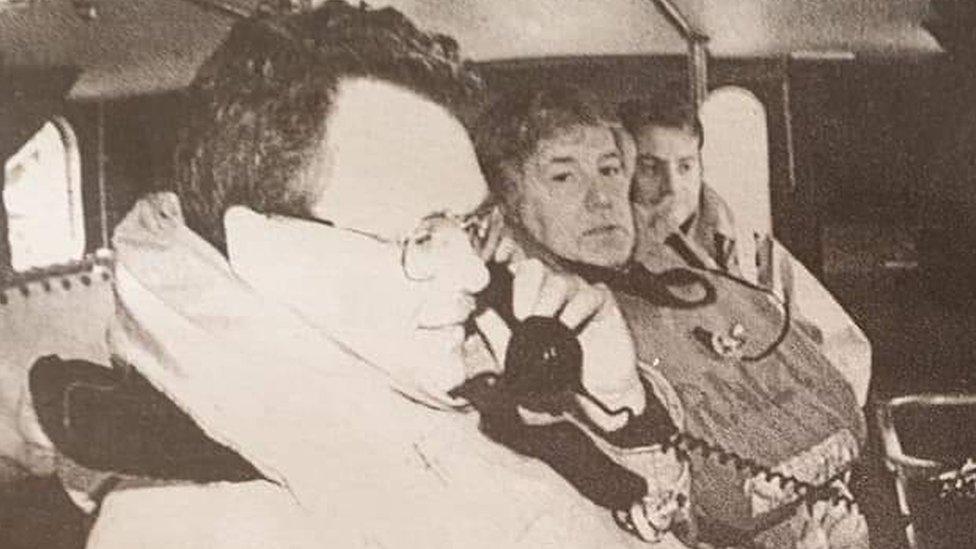

Geoff Cowan worked in the Merchant Navy

He said there had been a massive rise in swimmers in the bays around Cullercoats and some had to be spoken to about the risks they were taking, citing several who wanted to swim at Whitley Bay during the recent Storm Babet.

"At the end of the day, it's up to each person," says Geoff. "We can say 'we do not think that's a wise thing to do', but we can't stop them.

"They do not know what they do not know."

Cullercoats has a B-class inshore lifeboat

In his early days Geoff was kitted out in boots and oilskins.

"You were always soaking wet before you'd even started," he says, with a laugh.

Drysuits arrived in the mid 1980s, but there were only three or four for the whole crew to share. Now every volunteer has their own kit carefully arranged in the locker room, ready to be put on within a minute.

Cullercoats has had a lifeboat station since 1848

Each crew member is also fitted with a beacon which, in the event of them ending up overboard, should lead rescuers right to them.

"It's a bit different from when I started," Geoff says, reminiscing about the light on their vest which lit up in the water and would be the only visual aid to show someone's location.

Although he spends his time onshore now, teaching water safety - part of which included recording a podcast dedicated to Cullercoats - he still feels the same "adrenalin rush" when the alarm is raised.

Geoff says he has always enjoyed messing around with boats

"You think, 'how quickly can I get down there?," he says, adding: "And then you could be there 10 minutes or 10 hours.

"A lot of calls get cancelled or it's put down as a false call with good intent, which is where someone thinks there is a problem and reports it but there isn't.

"We don't mind that at all. We would much rather people called than didn't."

It's not easy for the crew's families stuck on shore awaiting news though, Geoff says, adding they "deserve medals".

He and fellow volunteer Brian Reeds, who has clocked up 40 years working for the RNLI, start discussing the "heart-breaking" Penlee disaster of 1981, external.

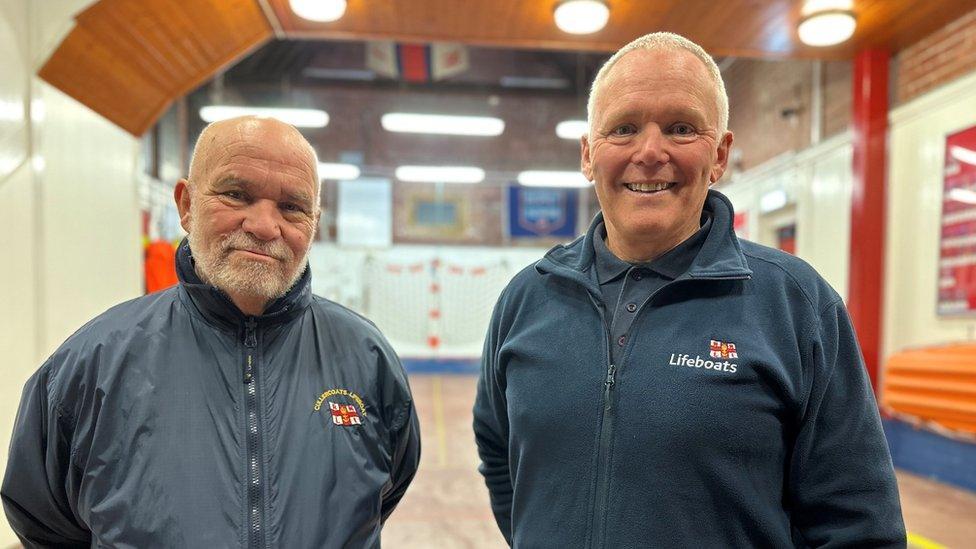

Brian Reeds and Geoff Cowan have clocked up a combined 90 years service for the RNLI

Eight Cornish RNLI crew and eight people from a stricken cargo ship were killed in fierce waves and hurricane winds.

"The coastguard was trying to call them on the radio and there was just deadly silence," Brian says.

It devastated the whole RNLI family across the country, Geoff says, but he adds: "If you think about these things too much, you probably would not go.

"But then there is a risk crossing the road.

"We do not think about it until afterwards."

Now Geoff enjoys passing on his experience to the new volunteers, many of whom work land-based jobs these day, unlike the fishermen volunteers who formed and ran the lifeboat at the outset.

"In 200 years we have gone from rowing boats, which if they capsized meant game over, to self-righting boats than can reach 25 knots," Geoff says.

"Who knows how we will be doing it in another 50 years, but the motivation will be the same - to save lives at sea."

Follow BBC North East on Facebook, external, X (formerly Twitter), , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published12 August 2023

- Published16 December 2022

- Published1 January 2021

- Published19 June 2017