Sir Terry Pratchett's study reproduced at Salisbury Museum

- Published

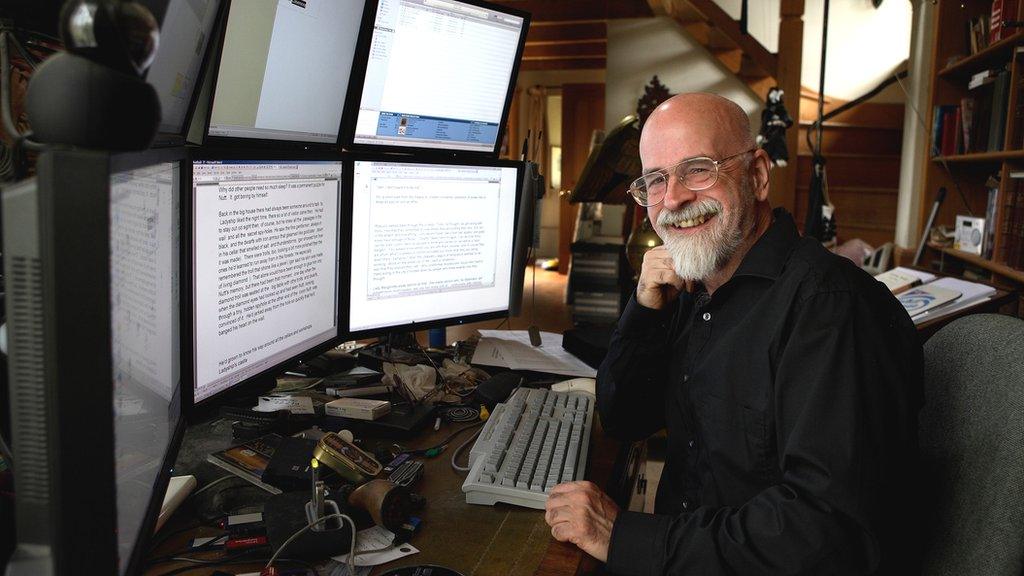

Sir Terry's office has been reproduced at Salisbury Museum.

"Left a bit… Right a bit...". Four men are struggling to squeeze a solid oak desk through the doors of Salisbury Museum.

It's not a particularly attractive desk. It's heavy, it's rather battered and the leather top is stained with coffee rings.

But this is where the magic happened. This was Sir Terry Pratchett's desk.

Two years after the Discworld author's death, this exhibition gives his fans the first opportunity to see his belongings up close and understand his creative mind.

"This is where he sat. This is where he wrote all those books. I can't believe it," explains his best friend and literary assistant, Rob Wilkins.

"It makes the hairs stand up on the back of my neck."

The author called the study at his home near Salisbury "The Chapel"

Every ornament, gadget and tool from Sir Terry's study has been placed in exactly the same place

Dozens of boxes filled with Sir Terry's personal possessions have been brought to the museum from the study of his Wiltshire home.

Now, under his friend's careful direction, they have been unpacked to create a replica of the cobwebbed workspace Sir Terry called "The Chapel".

Every ornament, gadget and tool is placed in exactly the right place.

"It feels great to show all this to the people who love his books. I want them to understand Terry better," his friend said.

Tortoise-feeding hat

The exhibition is every bit as eccentric as you would expect from a writer whose imagination ran wild over so many decades.

The display cases are packed with Pratchett paraphernalia, much of which has never been seen by the public before.

There's the bowler hat he wore while feeding his pet tortoises and the Olympia typewriter he used as a young journalist.

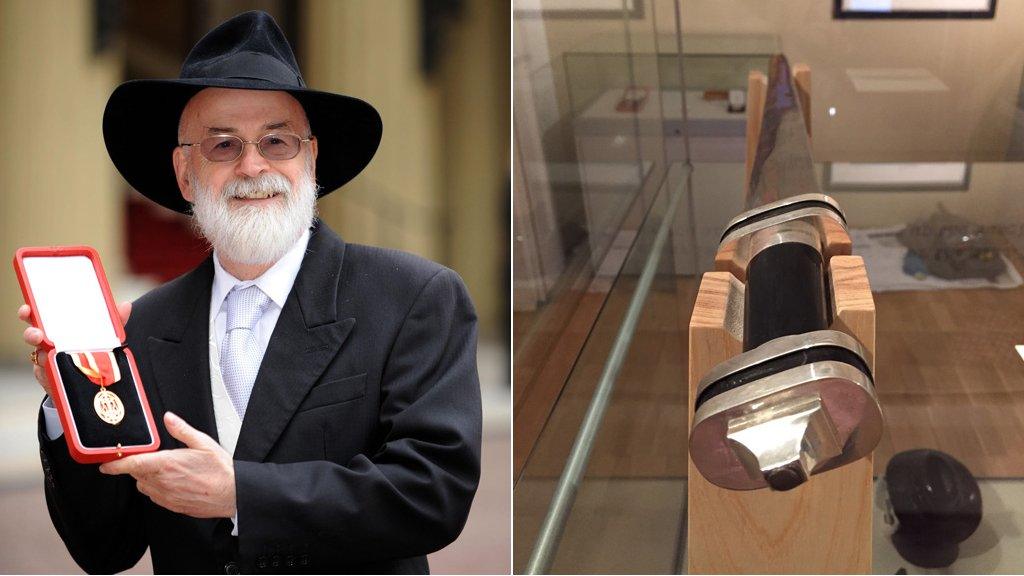

The Carnegie gold medal he was awarded in 2001 for The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents also features. Not to mention Sir Terry's iconic golden Discworld death ring.

Most of the items have been loaned by his family.

But pride of place goes to a stunning metal sword, polished so that it sparkles under the museum's spotlights.

Knighted in 2009, Sir Terry decided a knight needed a sword and created one from iron ore he collected in fields near Salisbury

"When Sir Terry was made a knight in 2009, he felt the one thing a knight needed was his own sword," Mr Wilkins explains.

"So he decided that he would make his own sword. He collected iron ore from a field in Tisbury. We smelted the iron, took it to a master blacksmith and Terry made his own sword.

"It's probably the most important thing in the whole collection because Terry made it himself. He felt it was magical."

Final novels

At times, it almost feels like Sir Terry is about to walk through the door.

His trademark Akubra black hat sits next to the leather shoulder bag in which he carried his notebooks.

On the walls are some of the illustrations and doodles he produced to accompany his written fantasy world.

While on a bank of computer monitors above the desk - resembling some kind of mission control - his words scroll across the screens.

His trademark Akubra black hat sits next to the leather shoulder bag in which he carried his notebooks

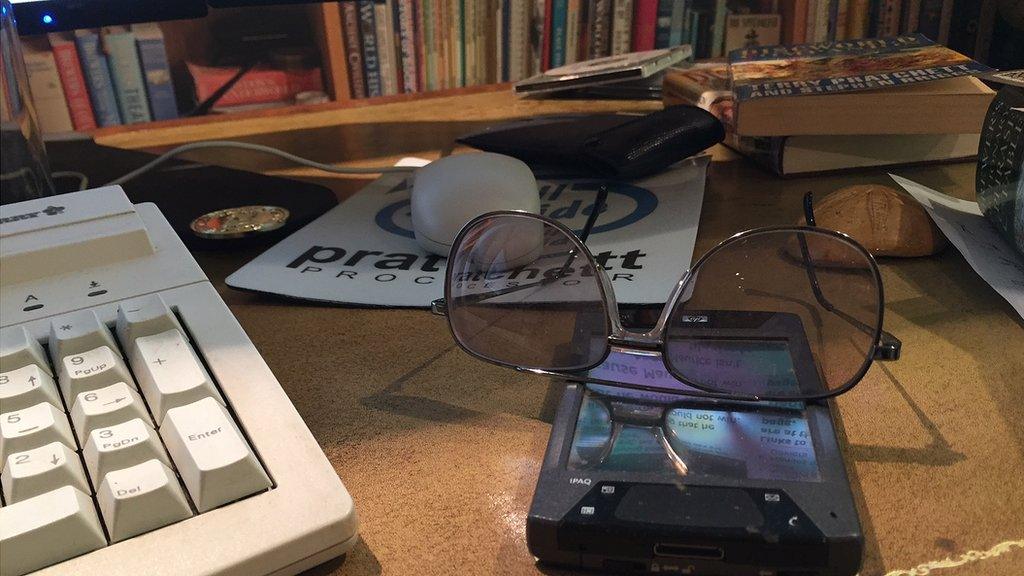

The exhibition covers Sir Terry's entire career, from his early teenage attempts at creative writing to the hard drive which stored his 10 final unfinished novels.

But if you were hoping to read them, you will be disappointed.

The hard drive has been crushed into tiny fragments, in accordance with the author's final wishes, so that no-one could ever read or edit them.

"He was very specific about having them destroyed," said Mr Wilkins.

"So we did it in style. We crushed the hard drive with a six-and-a-half-tonne steamroller."

The real thing

The attention to detail is remarkable. Carpenters and painters have recreated the fireplace and window from the office.

Life-size photographs of his cluttered bookcases line the wall, making it feel just as claustrophobic as the real thing.

Even the author's spectacles sit on the desk among his piles of papers.

The exhibition includes the hard drive of Sir Terry's unfinished works which was crushed by a steamroller as per his instructions

Life-size photographs of his cluttered bookcases line the wall while his glasses sit on the desk among his piles of papers

It is a surprising exhibition for a museum which typically displays local embroidery and the archaeology of Stonehenge.

But Sir Terry was well-known and well-loved in this area of Wiltshire, living just eight miles from the cathedral city of Salisbury in the village of Broad Chalke.

Visibly moved

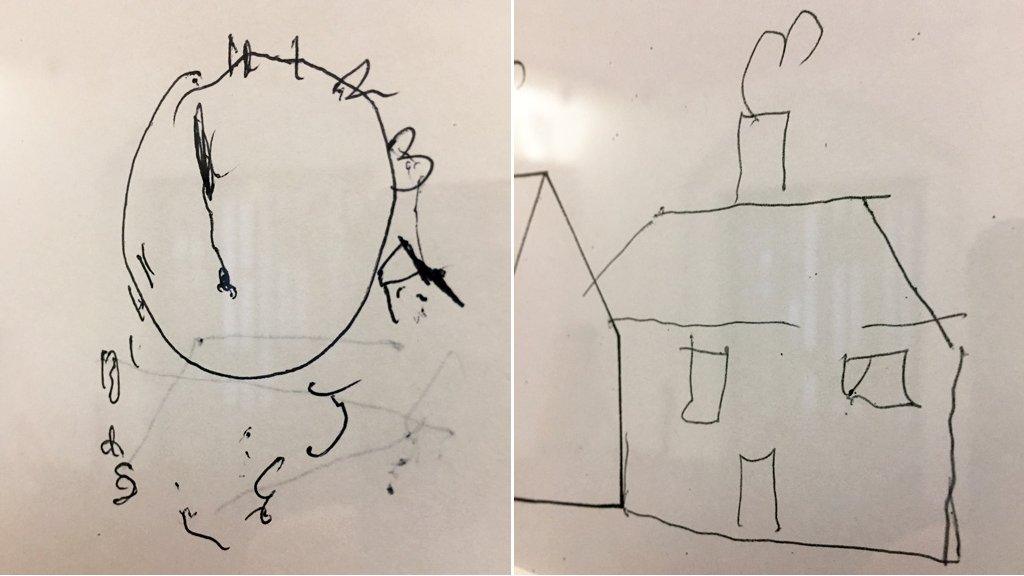

There are some stunning pieces of artwork by Pratchett's long-time illustrator, Paul Kidby, but the most poignant pictures are by the author himself, depicting his own struggle with Alzheimer's disease.

Scribbled on scraps of paper are his attempts to draw simple diagrams of houses and clocks when doctors were first assessing him.

Mr Wilkins is visibly moved to see these sketches but he says Pratchett always wanted to explain his disease to as many people as possible.

He says the pictures prove that, while Sir Terry's ability to draw was ravaged by his rare form of dementia, his story-telling skills were not.

"He could still write best-selling novels. He could still have 135,000 words scrolling through his brain," he said.

Poignant pictures by the author depict his struggle with Alzheimer's

"That was a good thing. It meant we were able to keep more of Terry alive for longer."

And that is what this exhibition is all about, keeping the memory of Sir Terry Pratchett alive for longer.

Terry Pratchett: His World opens at Salisbury Museum on Saturday 16 September and runs until January 2018.

- Published30 August 2017