Melksham father and son recall crash that changed their lives

- Published

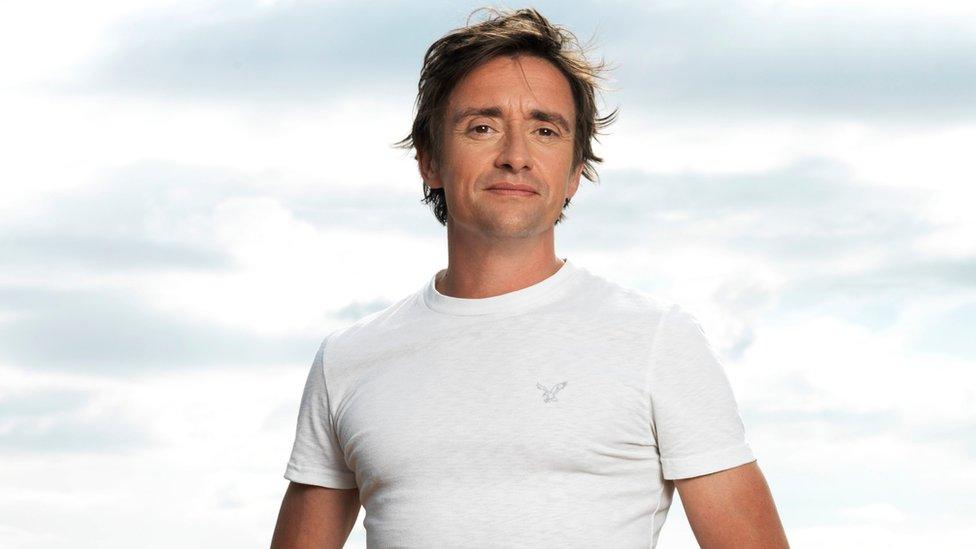

Jeremy (left) is once more cared for legally by his dad David (right)

A scar on Jeremy Syms' head is the only physical sign of the accident that changed his life.

Early in the evening of 23 September 2016, he had gone out cycling with his foster son, something he would not usually do, being a self-confessed "petrolhead".

But after he collided with a car at a roundabout, all memories of his previous life were wiped out and months of rehabilitation were to follow.

Mr Syms from Melksham, who is 57, got in touch with BBC Radio Wiltshire after hearing an interview with Richard Hammond about his own brain injury.

Like Hammond, he remembers nothing of the accident and very little of the hospital stay afterwards- something his father, David Syms, wishes he could forget.

'Close to death'

After David, 81, got a call to say Jeremy had been in an accident, he rushed to the scene in Melksham and saw his son surrounded by paramedics, bleeding from his ear and close to death.

David told BBC Radio Wiltshire: "I then went a little bit into panic mode and swore at him and told him not to dare die because his mother would never forgive him if he did."

David had already lost one child - Jeremy's brother who died from cancer in the 1980s.

Since the accident he now legally looks out for Jeremy's welfare.

Big financial decisions - like ones involving property - have to go through a court.

Jeremy in hospital recovering from the accident

Speaking to him and his father at Jeremy's home in Melksham, they share a sense of humour and seem jovial - but have been through an incredibly traumatic time.

The house shows Jeremy's past before the accident. Not only are there photos, the home was extended because of the foster children he and his now ex-wife cared for alongside their own.

But the fostering had to stop within days of the accident and eventually the marriage ended too.

Jeremy had to be assessed by a DVLA doctor to be able to drive again - which is also when he found out that medical notes from the hospital said he'd had three strokes.

David said: "He was lucky to survive."

Paramedics place Jeremy into an air ambulance

Pictures from the Wiltshire Times show the horror of the accident - the bicycle knocked over and multiple emergency vehicles at the scene.

Jeremy was taken to a nearby field where the Wiltshire Air Ambulance could land and was flown to Bristol's Southmead Hospital.

A coma, surgery and months of rehabilitation followed.

A notebook was put beside Jeremy's bed which for a short time nurses and family members wrote in.

Wreckage of Jeremy's bike lying on its side on the road

One note explains they had to take measures to make sure he didn't climb out of bed again.

He was later told he was so determined to get out of hospital, he once pulled out every tube that was attached to him. His arms had to be tied to the rails of the bed.

Jeremy can't remember it but he recalls other moments, like voices and a drill going into his head.

Before the accident, Jeremy said he had a great life and enjoyed being a father and foster dad and his work.

'I lived in utopia, I had a job I loved," he said.

"I had a management team that I worked for, they appreciated my capabilities, and I was very much on a high.

A close-up of the scars on Jeremy's scalp

"And life was pretty good, to be fair. In fact, it was pretty exceptional," he said.

However, like Hammond the majority of his memories from his previous life were gone and had to be filled in by friends and family.

His memories are now are based on what people have told him has happened.

David would show him pictures of his late brother, but Jeremy couldn't remember him at all.

"I had no recollection whatsoever," he said.

"And they played me videos, and they'd say, right, pick your brother - and if they hadn't given me the photographs... I couldn't."

Jeremy said his rehabilitation was about trying to "create a process to follow that's achievable" and recognising you are moving forward "rather than just plodding on".

He would put together daily timetables, detailing things like when he got up and loaded the dishwasher, showing he could cope with life.

He misinterpreted a lot of things and could not be negotiated with.

"If you said blue was blue, I'd tell you it was green," he said.

David said watching his son's experience has been very emotional, but added his son "spent most of his time winning".

Jeremy said the experience has left him with "a vivid belief in the afterlife".

He remembers being in a different place which he describes as being "a little bit like Lost Cities of Atlantis".

"It was very much sea-orientated, bright blue with people shouting through portholes."

He's since given a talk to medical professionals about what it was like and even won an award for his volunteering work in a hospital.

However, along with his humour, Jeremy is also very honest about his feelings with the situation and said there is a lot of stress, pain and anxiety that goes with what he has been through.

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published13 March 2023

- Published14 February 2023

- Published6 February 2023

- Published10 October 2018