Pewsey woman regains sight after going blind overnight

- Published

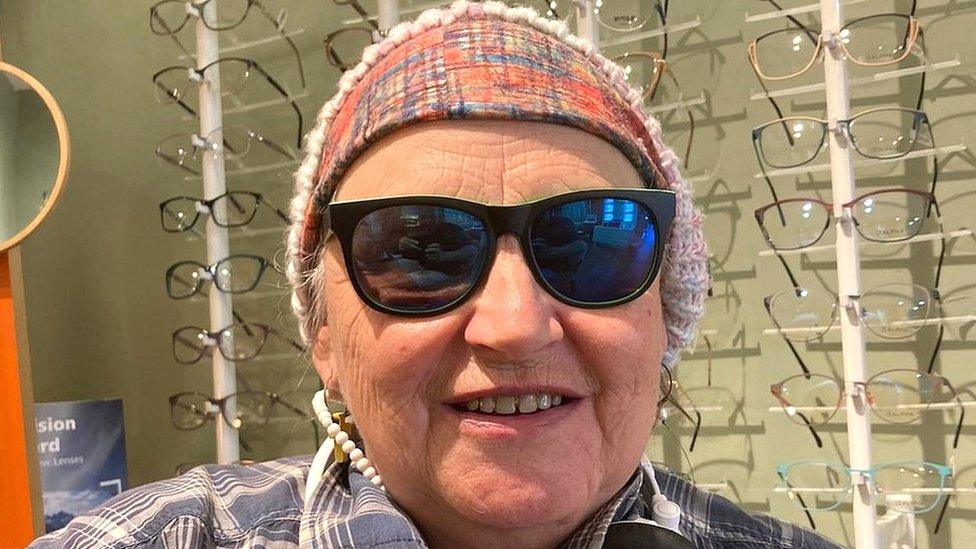

Hayley Martin had several treatments at the John Radcliffe hospital in Oxford

A woman's life changed when she unexpectedly went blind overnight because of a rare condition that attacks the optic nerve.

Hayley Martin, from Pewsey, Wiltshire, was recently diagnosed with MOG antibody disease (MOG-AD), which affects 1.6 in one million people, external.

She spent a week in total darkness, but thanks to treatment, her vision is slowly returning.

"You really don't appreciate what you have until it's gone," she said.

"It's like I'm seeing life all over again for the very first time."

Ms Martin, who happens to work at an opticians, said being blind for a full week felt like the longest of her life.

Her initial symptoms included feeling like there was too much light in her eyes

Ms Martin's symptoms started more than a month ago when she reported her eyes felt bruised - at the time though, she didn't think much of it.

She began to grow concerned as her symptoms continued to develop.

"My vision started going slightly funny. It just felt like I had too much light in my eyes, it felt like I was constantly having to blink," she said.

"That was when I thought, maybe something's not quite right."

Ms Martin decided to ask her work colleagues to take a look at her eyes.

They noticed the optic discs at the back of her eyes had started rising slightly, but not abnormally.

However, a few days later, she woke up with no sight.

"It was almost like my eyes were closed. I had to keep opening eyes thinking, 'They're definitely open', and that's when I realised I completely lost my vision," she said.

'Unknown' cause

MOG stands for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, which is ones of the sugary proteins that coats and protects your central nervous system and optic nerves and spinal cord.

Immunologist Dr Victoria Davenport explained how Anti-MOG antibodies work:. "They cause an autoimmune condition, where your own immune system attacks your brain stem and optic nerves, eventually creating lesions."

Dr Davenport, who is also an associate head of department for Biological and Biomedical Sciences at the University of the West of England added "the trigger for development of these antibodies is unknown."

Severe case

After being sent for treatment at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, a blood test confirmed she had the autoimmune condition.

Ms Martin told BBC Radio Wiltshire that during its research into the condition, the hospital has seen roughly around 300 cases in varying stages.

Unfortunately, hers was one of the most severe cases.

"The fact that they treated it so quickly and promptly was just unbelievable and that's why I'm recovering as well as I am," she said.

She underwent numerous treatments, including taking high dose steroids, a plasma exchange to flush out bad antigens and replace them with "good" ones, and an IV treatment involving human donation of plasma.

She was warned by doctors that a recovery was not guaranteed, she said.

"But the optimism and the support that they had right from the beginning - they were so encouraging. And that's how I managed to stay optimistic," she said.

Flashes of vision

As her treatment continued, she began experiencing "flashes of vision", where she would get small patches of clear sight which would disappear after a few seconds.

"After being in hospital for a week and a half, I felt like I had a jump in improvement where I could see the peripheral edges of my vision and that was really reassuring," she said.

"Central vision is still on and off, but it is much more than it was. I am able to be on my own now. Each day has little improvements.

"It puts so much in perspective. Just to see the clouds in the sky, even to feel the sun on your skin while looking at the sky.

"It just gives you a whole new lease of life. I'm going to appreciate things much more now."

Dr Davenport explained that symptoms like headaches and vision loss can be caused "by a number of other things, like infection".

"It's usually a one off and these people mostly recover vision without treatment," she added.

She said: "20-50% of MOG AD cases may recover, but more commonly it leaves a residual disability, or possibility of relapse."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

- Published12 June 2023

- Published6 June 2023

- Published14 February 2022