York Minster: BBC films for a year behind the scenes

- Published

A BBC team spent almost a year filming the work that goes into keeping York Minster open to the public

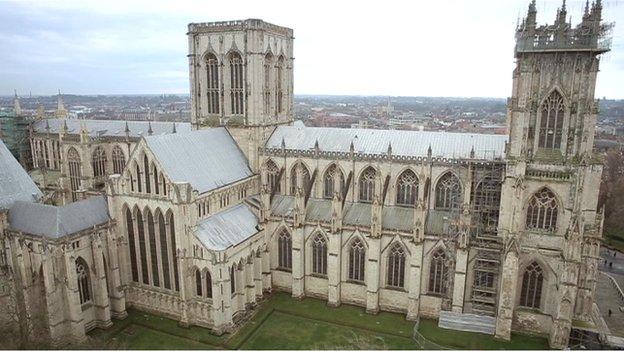

From every angle, York Minster dominates the city around it.

The central tower is large enough to fit the Leaning Tower of Pisa inside. The central nave is 260ft (80m) long and 100ft (30m) wide. The windows hold almost two-thirds of England's medieval stained glass.

But take a closer look and the minster is a vulnerable giant.

The current building has stood for 800 years and centuries of exposure to the elements have taken their toll.

In parts, the stonework is crumbling. Botched Victorian repairs, including the insertion of metal supports into the stone, are now rusting away.

The repair and restoration bill runs into millions and the complexity and scale of the job puts it on a par with the work on the rail bridge spanning the Firth of Forth in Scotland.

The east end of the minster is currently hidden behind 16 miles (26km) of scaffolding. It is one of the biggest cathedral restoration projects of its kind in Europe, will cost £20m and take another couple of years to complete.

The BBC has been allowed in to film behind the scenes at the minster for almost a year, capturing the unsung heroes whose work ensures one of Britain's great historic buildings is kept open and vibrant for all to enjoy.

Dean Vivienne Faull is the head of an organisation which employs 150 staff and more than 400 volunteers - the equivalent of running a successful medium-sized business

Heading up all this work, with what she describes as "a remarkable team of people" alongside her, is the current Dean of York Minster, the Very Reverend Vivienne Faull.

"At York Minster, the buck stops with me, in terms of the building and what goes on inside the building," she says.

"So all the restoration work and all the services, all the finances, all the strategic development - that is my responsibility, although I obviously don't actually do it all on my own."

The work is allowing a new generation of minster stone carvers to leave their mark on the building and, slowly, the weathered grotesques and gargoyles are being replaced.

One hundred and fifty feet above the streets of York a series of delicate medieval themed grotesques have been grafted back onto the building.

Looking down on the shoppers and tourists are a bizarre set of carvings with medieval ailments - including a victim of the plague and a rather ill looking Black Prince.

However, the biggest individual project has been the replacement of one mysterious weathered figure that sits above the east window. But the statue is so badly eroded there has been a bit of debate about who it once was and what it should be.

Stonemason Martin Coward says the techniques he uses have not significantly changed for 2,000 years

From his studio close to the minster, stone carver Martin Coward has been tasked with the design work.

A panel of experts have agreed that the original statue was probably St Peter - and it is Mr Coward's job to carve the replacement.

For the best part of 18 months he has immersed himself in the project creating various models that will be used as a template for the later carving in stone.

It will be his most significant project and a chance to leave his own lasting legacy on the building.

"The methods that I'm using are traditional, the techniques haven't changed much in a couple of thousand years," he said.

"It's the way we like to work here. St Peter was a fisherman, so he's slightly rugged and weather beaten. As long as he has a bit of a personality then I've achieved something."

The carvers at the minster often say it is "the building that sets the standard". Their job is not just to repair - but also to uphold the tradition of those who have gone before, giving the building the same care and attention their medieval counterparts did.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa could fit inside York Minster's impressive central tower

Tradition plays a big part in the life of the minster. There has been worship on the site for the best part of 1,300 years. It stands as a testament to human faith and the worship of God.

The atmospheric candlelit services at Easter and Advent would probably be recognisable to a monk from the 14th Century.

But like most big institutions the minster faces a challenge: how to hold on to the traditions that have served it so well while also moving with the times and attracting new people through the doors.

Part of the mission is to engage more with people living on its own doorstep.

Two million visitors enter the minster every year from all four corners of the globe. But attracting people from the city of York is a problem, even though entrance fees are waived for city residents. So if the locals won't come to the minster, then the minster is going to go to them.

Outreach workers are visiting local schools in the city to engage with the youngsters, some of whom know little about what goes on inside the minster.

The hope is that if the children can be enthused by the building and what happens inside it, then others will follow. In the battle for hearts and minds initial results appear positive. One teacher has described how the pupils are now turning into mini tour-guides for their parents.

It seems the minster's future may be in good hands.

A metallic 'orb' displaying conserved stained glass panels was installed in the minster to attract visitors

The three-part series 'The Minster' starts on Sunday, 16 March at 16:45 GMT on BBC One (Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and North East)

- Published9 August 2013

- Published25 May 2013

- Published12 December 2012