SS Rohilla: Dramatic three-day WW1 sea rescue remembered

- Published

The Rohilla struck a reef a mile from Whitby 100 years ago and sank with the loss of 85 lives

One hundred years ago, a World War One hospital ship ran aground just a mile off the North Yorkshire coast. The dramatic three-day rescue mission that ensued resulted in scores of lives being saved but spelled the end of the era of the rowing lifeboat.

It was a sea disaster which one survivor claimed was worse than the sinking of the Titanic. Yet the story of the SS Rohilla, which ran aground just a mile from Whitby 100 years ago with the loss of 85 lives, is largely untold.

"It was a tremendous tragedy and one of the biggest rescues in RNLI history," said Peter Thomson, RNLI volunteer museum curator. "The circumstances were just horrendous."

The World War One hospital ship carrying medical staff had left Scotland on 30 October 1914 bound for Dunkirk, in Belgium. But by the early hours, violent storms had thrown the passenger steamer off course.

The captain believed he was miles from the Yorkshire coast, having estimated his location using his last known position off the coast of Northumberland.

But unbeknown to him, the ship was merely miles from Whitby and its jagged rocks.

"There were no navigation lights on shore because of the war," said Mr Thomson. "So the poor captain had no idea where he was and when he got to the Yorkshire coast, he drove straight into the cliffs."

The ship broke in three sections - first the stern sank, killing most of the people on board that section of the ship. Those left on the rest of the wreck were stranded as it broke up over the course of three days.

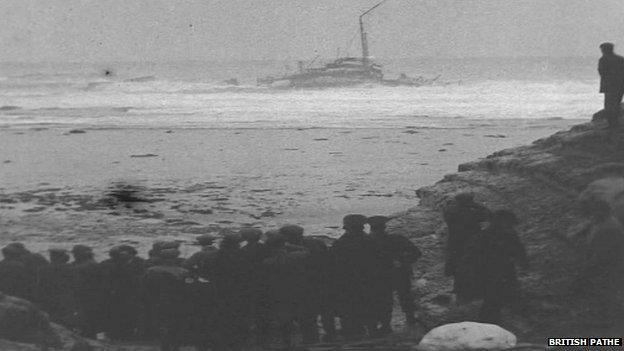

Crowds gathered on the cliffs and watched in horror as the hospital ship sank

Many of those on board jumped into the water and tried to swim to shore

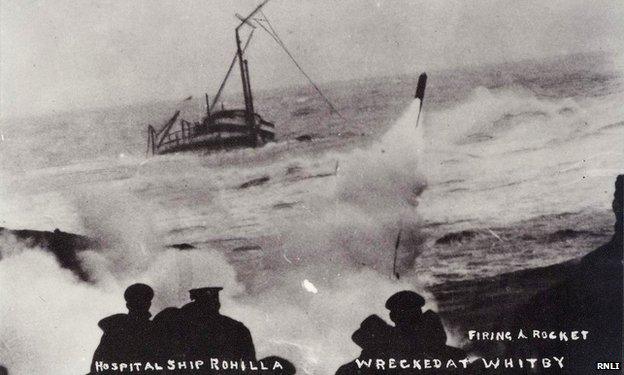

Rockets were fired from the shore to try to secure a line to the doomed vessel

The Rohilla hit Saltwick Nab at 04:00 GMT, a 400 yard-long reef about a mile east of the North Yorkshire town.

Crowds gathered on the cliff tops and watched in horror as a tragedy seemingly within arm's reach unfolded before them.

Rockets were launched from the shore but were unable to secure a line to the ship. The raging storm hindered rescue attempts and the RNLI had to wait until dawn broke before sending out its first rowing boat.

The vessel was dragged along the rocks opposite the wreck and crew members rescued 35 of the 229 on board in two trips.

One of the five women rescued was Mary Roberts from Liverpool - though she was no stranger to luck. The stewardess had survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic just two years before.

Mary Roberts, left, survived both the sinking of the Titanic and the Rohilla

"She is known to have said that of the two disasters, the Rohilla was worse because of the storm and the ship breaking up beneath them, whereas the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank quickly in calm waters," said Mr Thomson.

Despite its initial success rescuing those trapped on the ship, high swells and extreme wind had badly damaged the rowing boat on its second journey.

"They didn't dare make another journey," said Rohilla expert and diver, Colin Brittain. "It must have been horrendous for those on board waiting for rescue seeing the lifeboat hauled out of the water. But there was nothing more they could do."

Calls were made to neighbouring lifeboat stations but they were faced with the same stormy conditions as Whitby.

In an ambitious plan, a lifeboat was lowered down a cliff in the shadow of the town's Abbey by hundreds of men. But that attempt was aborted when they realised the boat could not be launched in such bad weather.

Fearing rescue attempts were not being made, many of those left on the Rohilla became desperate and jumped in the sea. The people of Whitby began forming a human chain and waded into the shallows to help those that made it to shore.

Crowds formed a line on the beach to wade out to help survivors

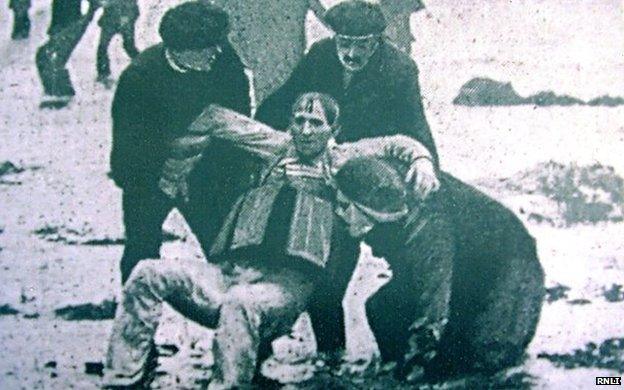

Those that survived the stormy waves were beaten black and blue by their ordeal

The lifeboat was dragged across the rocks in an attempt to reach the Rohilla

"It probably seemed feasible being a few hundred yards from shore," said Mr Brittain, "But the extreme weather took a toll on those trying to swim and very few made it to shore. Most floundered and were never seen again."

The following afternoon, as the Rohilla continued to crumble in the sea, the motor lifeboat Henry Vernon, stationed at Tynemouth, set off for Whitby. But the crew had to wait until the next day when the storm had calmed before it was able to reach the remaining 50 survivors.

Last off the ship was the captain who, according to legend, had the boat's black cat tucked under his arm.

Ann Raymont's great-great-grandfather, Richard Eglon, was instrumental in the final journey to the doomed ship.

She said: "When the Rohilla disaster happened they didn't have anyone that could pilot the Tynemouth lifeboat so my my great-great-grandfather piloted it. They took off the last 50 people and a cat.

"It was very remarkable. Men just walked into the sea to try and rescue people."

As the church bells rang out across Whitby to mark the end of the rescue mission, people wept at the sight of those being bought back to land, beaten black and blue from battling the wreckage.

Though 144 people were saved, the disaster was a turning point for the RNLI.

"It made lifeboat crews realise the future lay in engine-power instead of rowing boats," said Mr Thomson. "Four of the lifeboats involved in the rescue were rowing lifeboats but it was only the Henry Vernon that was able to reach the remaining survivors.

"People had been suspicious of motor lifeboats until then but this helped convince the crews that they really were the future."

The wreckage of the Rohilla is still visited by divers

Though the story of the Rohilla is unfamiliar to many, its wreckage remains in the shallow waters of Whitby and is regularly visited by divers.

Mr Brittain, who has explored the ship's remains more than a hundred times, said many of its features were still recognisable.

"You can see the sides of the ship although they've been flattened, and you can see the holes where the port holes used to be," he said. "There's various parts of engine, the hull is still there and there's an area where the wash rooms used to be that had large red coloured tiles on the floor and small, white hexagonal tiles on the walls.

"It's very recognisable, very picturesque."

A series of commemorative events will be held by the RNLI in Whitby from 31 October to 2 November to mark the centenary of the Rohilla disaster.

.jpg)

A commemorative service was held in Whitby on the 60th anniversary of the disaster

- Published17 August 2014