Census 2021: Can Richmondshire's population drain be reversed?

- Published

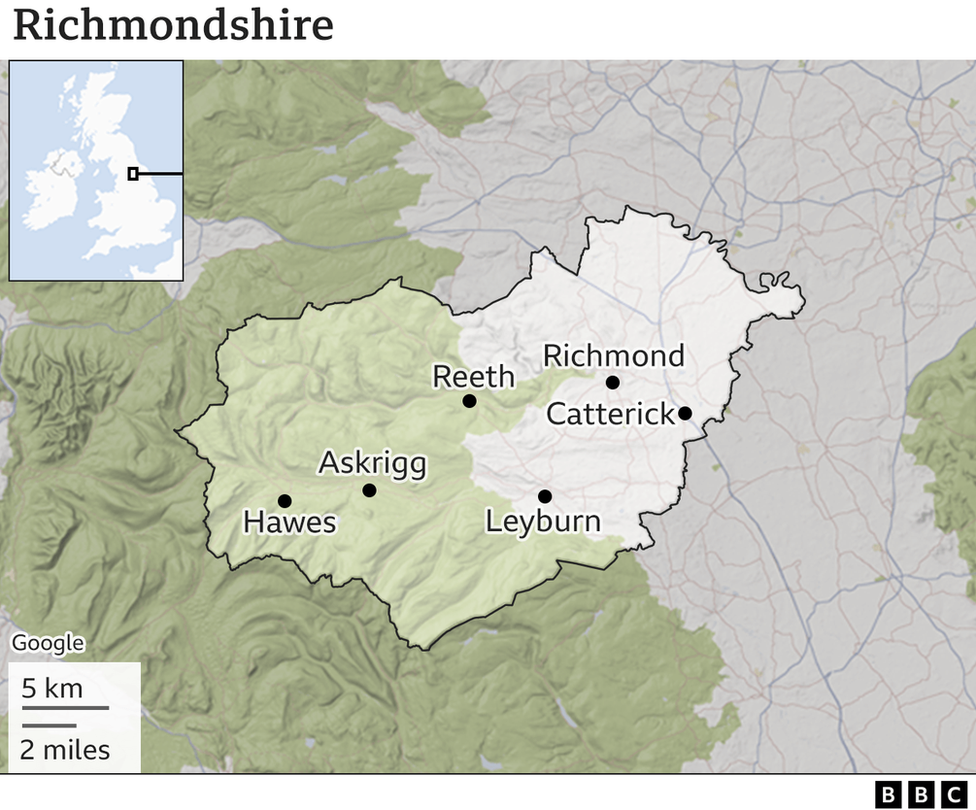

Richmondshire in North Yorkshire is one of the most sparsely populated areas of the country

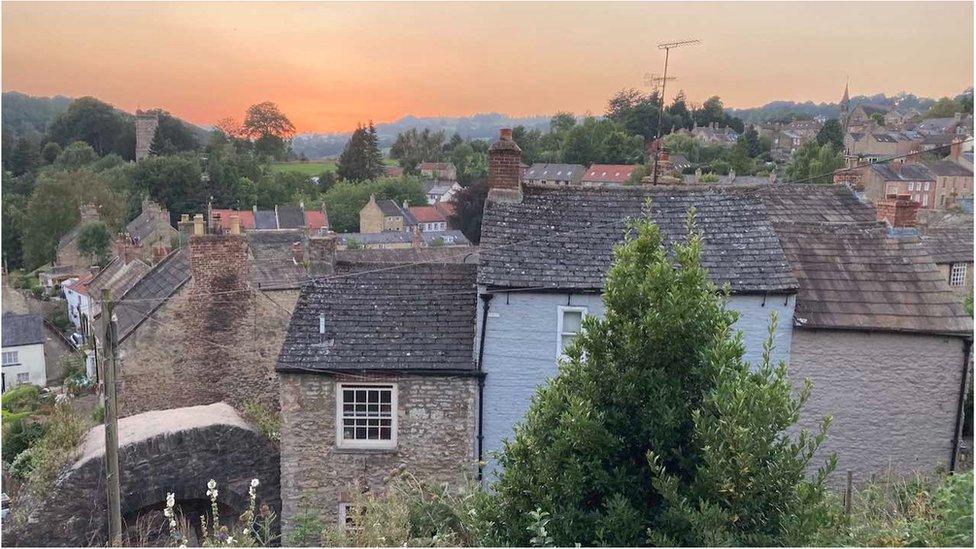

The Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire may be as picturesque as they come, but it also has one of the most rapidly declining populations in the UK, according to the latest government census.

So why are people deserting the district and what is being done to address the problem? BBC News spoke to people in the sprawling and historic Yorkshire Dales idyll to find out.

"I don't think people can afford to live in Richmond itself. It has gone up considerably in the last three or four years," says 57-year-old Sarah Uludole.

Stopping for a moment on a side street off Richmond's bustling cobbled Market Place, Mrs Uludole pinpoints that rising house prices are one of the biggest issues facing people who are wanting to stay in Richmondshire - and especially in Richmond itself.

"There isn't a lot of employment in the area and the young are probably being pushed out by very expensive house prices," she says.

"Others are moving from other places and are buying up the houses before they're even on the market for a day or two and the prices have soared."

Despite the influx of people with money, the trend in the wider area is one of people leaving.

The number of residents in Richmondshire shrank by just over 2,000, or 4.4%, during the last decade - compared to the number of people in England as a whole which grew by 6.6%.

Sarah Uludole says she works in Richmond but cannot afford to live in the town

Mrs Uludole's observations about house prices are backed up by figures from estate agents Zoopla.

The average cost of a property in the historic market town is £285,889, according to Zoopla, while properties in the nearby military town of Catterick - where Mrs Uludole lives - are more than £100,000 cheaper.

Not only are house prices soaring, but the rate of that increase in prices has shocked people from the area who are attempting to get on the housing ladder.

The district - which predominantly sits in the Yorkshire Dales National Park - has recently seen faster price rises than anywhere else in Britain, with figures up 29% between 2020 and 2021.

Stepping out from one of Richmond town centre's many ginnels, local resident Becca Wright, 26, says: "We pay just as much as Londoners to live here."

She adds: "The rent is extortionate if you're lucky enough to get a house, whether that's through housing association, council or private rented, because there's nothing."

Richmond resident Becca Wright says the town is full of "hairdressers, charity shops and pubs"

Housing aside, Ms Wright says she believes other issues prevent young people from staying in the area, too.

"If you want to go to college, the nearest one is Darlington and you'd have to pay for a bus. So people aren't going for it because they can't afford it," she says.

As a consequence, Ms Wright says: "There are more young people who don't have a job because they don't have the education as they couldn't afford to get it."

She adds that she thinks there is also a lack of facilities: "There's nowhere for the teenagers to go, so they just go about and cause trouble. There are no youth centres."

Surrounded by lush green rolling hills, Richmond's attraction for the retired population is obvious, but parents and grandparents still clearly worry about the future outlook for younger generations.

Sitting in the sun while waiting for a bus, 76-year-old former teacher Rodney Hall says: "It's one of the nicest places to live. You've got the Georgian town centre, people are laid back, and to me it has everything.

"But once young people have got their A-levels, they go to university and never come back.

"My daughter has just finished them and is going away to study English Literature. She won't come back to Richmond," Mr Hall says.

Rodney Hall says Richmond is one of the nicest places to live, but "young people leave and don't come back"

According to councillor Stuart Parsons, leader of the North Yorkshire Independents party on the county council, Richmondshire as a whole is "perceived to have very little to offer young people in terms of things to do".

Mr Parsons says: "The government has enforced the rule of people staying in education until they're 18 unless they do an apprenticeship.

"There is no university in North Yorkshire, so every year there is a drain as young people go outside for their education."

Mr Parsons adds that on a wider level, during a cost of living crisis, the difficulty of being based in areas sought out for their natural beauty is worsened by the lack of job opportunities and the quality of paid work available.

"Richmond is perceived to be a wealthy town, but 40% of people are on zero hours contracts or on minimum wage. Try getting a deposit on those wages," he says.

Meanwhile, Rachel Allen, from Citizens Advice, who has helped to support both young and old people living in the area, adds: "These aren't people based at home doing highly paid jobs remotely. They have to travel to work and the cost of fuel at the pump has hit £2 a litre at my local garage."

Councillor Stuart Parsons says a lack of higher education opportunities sees young people heading elsewhere

The geography of Richmondshire, the fourth smallest local authority district in the country and one of the most sparsely populated, external, also creates some unique issues for those who live and work there, Ms Allen says.

"Our local office is in the town of Richmond, but we serve an exceedingly rural area reaching up Wensleydale and Swaledale.

"It's a few market towns with a large amount of rural sparsity," says Ms Allen, the charity's head of partnerships, who has lived in Richmondshire for more than 25 years.

"Not only do we have a very dispersed population, but we have real problems with broadband connectivity and mobile signal."

Meanwhile, the Covid pandemic also exacerbated existing rural problems, especially for older members of the population, Ms Allen says.

"We have an elderly population who are now experiencing greater health inequalities as they can't afford to travel or gain access to travel to appointments."

Richmondshire includes market towns and villages such as Middleham (pictured), Hawes, Reeth, Leyburn and Catterick

With the challenges a rural patch creates, how do those in positions of authority fight the decline in numbers?

North Yorkshire County Council went about establishing a rural commission in late 2019 to identify its biggest challenges and how to overcome them.

Carl Les, leader of the county council, says: "Among the recommendations were a levy on the owners of second homes and an overhaul of the government's funding formula for both education and housing.

"The county's economy also needs to be focused on the green energy sector."

A rural taskforce has also been meeting regularly to discuss further solutions, Mr Les says.

It is due to publish its battleplan later this year in a bid to help bring back a "missing generation" of residents, as he describes it.

The average house price in Richmond is currently £285,889, while homes in nearby Darlington can go for under £100,000

"If North Yorkshire had the same percentage of younger adults per head of the population as nationally, there would be more than 45,500 extra younger working age adults living in the county than there are today," Mr Les says.

"This would mean the county would have a £1.5bn boost to its economy each year."

For Ms Allen, though, there is a long distance to go before Richmondshire reverses its declining population.

"A village becomes less attractive to young families because the school is getting smaller and might close," she says.

"It then closes, and suddenly there's no reason for a family to move there.

"I'm rooting for Richmondshire, but the problems are pretty immense for growing it into an economy where you've got young families coming back."

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published13 September 2021

- Published3 July 2021

- Published27 April 2022

- Published14 October 2019