Tree killing disease spreads to NI

- Published

Trees affected by the disease are being felled

A private woodland and two government-owned forests in Northern Ireland have been devastated by an outbreak of a killer disease.

It has become known as Sudden Oak Death, but it is really a fungal-like infection that kills Japanese larch trees.

It has already wreaked havoc in England and Wales destroying hundreds of acres of woodland. Now it has arrived in Northern Ireland.

But the reality is that it has been in Northern Irish woods for some time.

No-one seemed to have spotted it until Lord Rathcavan became worried about a stand of Japanese larch trees on his estate near Broughshane in County Antrim.

They were shedding their needles and were dying.

Initial tests with the Department of Agriculture indicated that it wasn't Pythophthora ramorum, to give it its proper title.

Unconvinced, Lord Rathcavan had samples sent to the Forestry Commission in England. There was no doubt. His trees did have the disease.

Lord Rathcavan sent samples of trees away for examination

Within days he was served an order to cut them down to prevent further infection.

"I'm to fell this wood completely, all eight acres of it," he explained to the BBC.

"I have to destroy and burn what they call the lop and top (the branches and the top of the tree) and I have to destroy all the ponticum (Rhododendron) you see round here."

Rhododendron is also a host for the disease and many of the plants near the larch trees were withered.

Lord Rathcavan has taken bio-security into his own hands to try and prevent the disease spreading to other trees on his estate.

He's put straw bales in streams to stop the infected needles from infecting further down stream.

Notices ban people from his woods and all staff must spray their boots and use a disinfectant mat when leaving wooded areas.

He finds it ironic that he is being forced to cut his trees down by law when a few miles away are two government-owned forests, Ballyboley and Woodburn, both badly infected by the fungus.

Indeed he suspects that is where fungal spores came from.

"I believe from talking to people who live around Ballyboley and Woodburn that these larch woods have had similar signs of this disease for two years. So the locals tell me."

He believes that fungal spores had been carried on the prevailing winds to his woods.

The BBC contacted the Forestry Service about the disease at the beginning of July, but the claim that it was present in Northern Ireland was dismissed.

That was despite the fact that huge stands of larch trees in two of their forests were clearly dying.

But they insisted there was no link to the "Sudden Oak Death" fungus, despite the fact that there were warnings to woodland owners to be on their guard for the disease.

The warning had come from the Northern Ireland Forestry Service. Ironically, the fungal spores were already attacking their own trees, but it seems they hadn't spotted it.

Because the trees weren't suspected of harbouring the disease, they were left standing and the spores were free to be carried off on the wind.

So while Lord Rathcavan watched the trees planted 65 years ago by his grandfather being felled, acres of infected trees still stood in the government-owned forests.

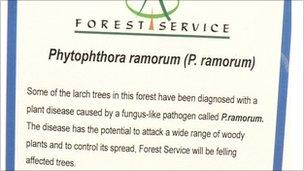

A warning sign put up by the Forestry Service

I visited Ballyboley forest and was surprised to discover the public were still allowed open access.

They were able to walk over the diseased needles lying on the pathways.

The only bio security in place was a notice urging people to make sure they didn't walk the needles out of the forest and to suggesting they washed their shoes and boots.

I stood and watched as a gentle breeze blew more needles off the dying trees and onto the path.

Aware that up until then the service had denied the existence of the disease in Northern Ireland and that there was no mention or warning of it on its website, I rang them to ask for an interview.

Within an hour they issued a press release admitting that the disease (P. Ramorum) has been diagnosed in Northern Ireland.

Why was the Forestry Service taking so long to react to what was rapidly becoming a crisis?

Shouldn't they have put two and two together and realised something was terribly wrong?

Stuart Morwood of the service told the BBC that they had been waiting for the appropriate molecular confirmation of the disease.

"We are just about to start our felling programme. You will see that activity in the very near future and we have got a significant programme that will take us into spring of next year to remove those trees."

Shortly after the interview ended, a hurried message was sent to me to the effect that they would now start felling the trees in two days time.

Meanwhile, Lord Rathcavan could only look on as tree after tree was felled in his woods.

He has been forced to cut them down by the same government department that has yet to fell a single infected tree of its own.

And he has to pick up the bill for the work on his land. The initial quote runs into tens of thousands of pounds. He hopes to have all his trees down in a few days to prevent further spread of the disease.

But with two infected forests with trees still standing downwind of his land, it is more in hope than reality.