Claudy bomb: A dark day in the bloodiest year

- Published

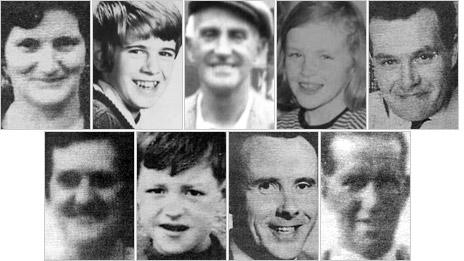

Nine people died when three bombs exploded in Claudy. From top left: Rose McLaughlin; Patrick Connolly; David Miller; Kathryn Eakin; Joseph McCluskey; Elizabeth McElhinney; William Temple; Arthur Hone and James McClelland.

On 31 July 1972, three car bombs exploded on Main Street in Claudy, County Londonderry, killing nine people.

No paramilitary group has ever claimed responsibility for the attack and no-one has been convicted of carrying it out, though there is little doubt the IRA was behind it.

1972 is regarded as one of the worst years of the Troubles with 496 people losing their lives.

More than 250 were civilians, 132 were soldiers and 17 were members of the RUC.

Many remember that year for the events in Londonderry on 30 January when 13 people were killed by British paratroopers during a civil rights march in the city.

It became known as Bloody Sunday.

The next month the government at Stormont was suspended by the then British Prime Minister Edward Heath and Northern Ireland got its first secretary of state.

Throughout the year car bombs ripped through Northern Ireland.

In Belfast, on 21 July, more than 20 bombs exploded over 75 minutes, killing nine people and injuring a further 130.

Almost 100 people died in the month of July alone, the nine in Claudy would be the month's last casualties.

Cover-up

The first car bomb exploded outside pub shortly after 1000 BST. Three people were killed instantly, with three others fatally injured.

Merle and Billy Eakin lost their daughter Kathryn in the first explosion

The second car bomb was discovered by police near the post office. People were evacuated from this area towards the Beaufort Hotel where a third device had been left.

Three people were killed instantly when it exploded.

It is believed the IRA were behind the attack, but they have never claimed responsibility for it.

Both Protestants and Catholics were killed in the blasts.

The youngest victim was eight-year-old Kathryn Eakin who was cleaning the windows of the family grocery store when the bombs exploded.

The other people killed were, Joseph McCluskey 39, David Miller aged 60, James McClelland 65, William Temple 16, Elizabeth McElhinney 59, Rose McLaughlin aged 51, Patrick Connolly, 15, and 38-year-old Arthur Hone.

In 2002, an investigation was launched by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland, following an initial probe by police.

Part of its remit was to investigate claims that the British government, RUC and Catholic Church conspired to cover-up the activities of a Catholic priest who was a member of the IRA bomb team.

Shortly after the bombs, it emerged that one of the suspects was parish priest Father James Chesney.

Father Chesney was the curate in Cullion, one of the smallest parishes in County Londonderry.

It was rumoured that he was an active member of the South Derry brigade of the IRA. It was claimed he had joined up in the wake of Bloody Sunday.

No warnings were given as the bombs exploded in the village

When the allegations of his involvement reached the Catholic Church, he was called in for questioning by the then Bishop of Derry, Neil Farren.

Police confirmed in 2002 that a priest was a member of the IRA and was involved, but had never been questioned.

In 2002, Bishop Farren's successor, Edward Daly, told the BBC that Father Chesney had denied any involvement with the IRA "utterly, unequivocally, vehemently".

However, he did tell his superiors that he had "republican sympathies, very strong republican sympathies".

Father Chesney died in 1980.

In 2005, four people, including a Sinn Fein Assembly member, were arrested in connection with the bombing.

They were released without charge a few days later, with Sinn Fein's Martin McGuinness calling it a political stunt.

Justice

Speaking in 2002 shortly after the investigation reopened, Merle Eakin, who lost her daughter Kathryn in the attack, said: "We are just hopeful that they will bring justice and the people who are still alive will be brought to justice - that is what we really want."

Relatives have called for an inquiry into the events of Claudy and the suspicions of a cover-up afterwards.

The families of those killed have for many years said that they have the same right as the families of those killed on Bloody Sunday to find out what happened to their loved ones.

But with the Saville Inquiry running for 12 years and costing £195m, the government is unlikely to sanction one.

With the Police Ombudsman's report, the families hope some of their questions will finally be answered.